On, Voyager

Mary Gross

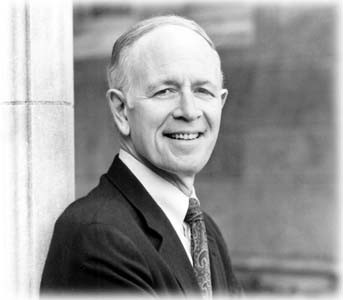

Lost in the Translation: Professor Robert Fagles immersed himself in ‘The Odyssey’ for seven long years.

Robert Fagles hits a Homer with his new ‘Odyssey’ translation

By Zack Stentz

IN 1995 IT WAS JANE AUSTEN. Last year it was Shakespeare. Now the latest titan of Western literature to be dusted off and celebrated in popular culture appears to be none other than that oldest, deadest Dead White European Male of them all: Homer. Despite predating by 2,700 years the average Hollywood executive (except maybe Lew Wasserman), the presumed author of The Iliad and The Odyssey finds his work at the center of network television’s May sweeps period, as NBC unveils a $30 million, four-hour miniseries of The Odyssey (starring Armand Assante as Odysseus and Isabella Rossellini as the goddess Athena).

And on the literary front, an acclaimed new translation of The Odyssey (Viking Penguin; $35) by Princeton literature professor Robert Fagles (the New York Times called it “a memorable achievement” and “a worthy successor” to his similarly praised 1990 translation of The Iliad) has emerged as 1997’s unlikeliest bestseller, selling an incredible 50,000 copies in hardcover and 9,000 in its audiocassette version.

No one could be more pleased with this state of affairs than Fagles himself, who’s had Homer as a constant houseguest in his brain for even longer than anyone Penelope ever entertained. “And I’m glad to say it,” Fagles laughs, speaking over the phone from his Princeton office, “because I’d rather have Homer on or in the brain than Penelope’s suitors.”

Asked to account for The Odyssey‘s current prominence, Fagles replies: “The Odyssey is a postwar poem, a poem of readjustment, and I think in some sense a postCold War poem. I think one reason there’s so much responsiveness to The Odyssey right now is that in many ways we’re in a postwar period.”

But postwar doesn’t mean post-violent conflict, and echoes of Homer appear nearly everywhere in the contemporary world. Psychiatrist Jonathan Shay’s 1995 book Achilles in Vietnam looked at his Vietnam veteran patients’ post-traumatic stress disorders in the light of The Iliad’s infamous “rage of Achilles,” a fury that also seemed manifest on CNN as the long standoff at the Japanese embassy in Peru abruptly ended with a sudden burst of merciless violence.

“Actually, it’s almost Odyssean,” says Fagles of that incident, “in that the sudden strike had been brewing for a very long time, until the time was absolutely right. And that’s of course echoed in books 13-22 of The Odyssey, where there’s a very long wait until the strategic moment arrives, and Athena tips off Odysseus that the time is now to strike.

“At the same time,” he counters, “I don’t want to limit Homer to his relevance to our own age. It’s there, and it’s very powerful, but in other ways the poem is very strange, and very distant in time, so it’s a kind of two-way street. The poems are very available, and very contemporary feeling, yet at the same time a good deal grander, a good deal larger, and a good deal more imaginative than our lives are in the 1990s.”

Oliver Upton

Long Strange Trip: Armand Assante plays Odysseus in the NBC special.

A primary reason for the praise showered upon Fagles and his work stems from his largely successful effort to walk the knife edge between a lifeless adherence to the literal text and opting for a translation so idiomatic it becomes “Robert Fagles’ The Odyssey.”

“Well, all translation involves this tug of war,” Fagles explains. “You have one foot in the past, some 2,700 years ago, and you have to be loyal to it, master the Greek, master the commentaries, master the lexicons.

“And on the other hand,” he adds, “you have the challenges of your own language, in this case American English, and all the great things that have been written in it. And the goal is to bring those two together, to bring that ancient text into the language we speak here and now.”

In other words, “every generation needs its own Homer” as the cliché goes, though Fagles admits that “any translator worth his or her salt hopes his or her translation will last longer than one generation. [18th-century English author Alexander] Pope’s Homer was the English Homer for 150 years.”

Its longevity aside, Pope’s Homer also provides a warning to the translator who would go too far in substituting his own words for the original, as 18th-century classicist Richard Bentley accused when he wrote: “It is a very pretty poem, Mr. Pope, but you must not call it Homer.”

Fagles avoids some of the pitfalls of earlier translators partly through clever renderings of the repeated epithets attached to characters: he translates polutropos, the word Homer often uses to describe Odysseus, as the wonderfully evocative “man of twists and turns.”

“Many of the epithets demand a sort of flexibility,” Fagles explains, “as with one epithet used to describe Odysseus, polumetis: ‘full of cunning,’ ‘full of resources.’ His resources vary according to context, and to simply repeat a phrase serves little purpose, especially if you grant the fact that Homer the performer could vary the epithet through inflection or the nuance of his voice.”

Homer the performer. This is a critical phrase in understanding Fagles’ approach to his work, which treats The Odyssey as not just a literary document but a work to be performed aloud, just as in Homer’s day. “Once you get that Greek hexameter [the rolling, six-beat line form in which Homer composed] in your ear, it becomes the most gorgeous line of poetry ever conceived,” says Fagles. “And the more it lodges, the more you realize there’s nothing like it in English and you mustn’t try to reproduce it.”

So did Fagles’ two decades of daily contact with Homer (as long as Odysseus himself spent away from Ithaca) make the act of translation a purely technical chore? “No, no, the technical part is just the start of it,” Fagles replies. “The more I became involved–and I’m an inveterate tinkerer–the more deeply I became engaged with the story and the personalities. You have to, because if you grant Homer was a performer, remember that 70 percent of The Odyssey is direct discourse. All kinds of people are talking, and talking to each other.

“There’s nothing more important to me when trying to translate than a sense of cadence,” says Fagles. “I’m always mumbling when I’m trying to translate.”

A habit that must be troublesome in public situations. “You get some odd looks,” he laughs, “but you learn to live with them.”

So be warned. The next time you find yourself standing next a person lost in thought, muttering rhythmically to himself or herself in some unknown tongue, don’t necessarily back away and call for the men in white coats. He or she might just be working on the next translation of Homer.

From the May 8-14, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

© 1997 Metrosa, Inc.