Reading Finis Dunaway’s Defending the Arctic Refuge: A Photographer, an Indigenous Nation, and a Fight for Environmental Justice, it’s hard not to think about the passage of time.

Specifically, how the age-old cycles of nature collide with the cycles of American politics.

On the surface, Dunaway’s book, which recently won a Spur Award from the Western Writers of America, chronicles the unlikely role of a Sonoma County activist in a decades-long campaign to protect a breathtaking piece of Alaskan wilderness from oil drilling.

In 1980, Congress established the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a 19-million acre region in northeastern Alaska. In the establishing legislation, lawmakers designated a 1.5 million-acre coastal region, formally known as the 1002 area, as open for oil drilling in the future pending Congressional approval. Ever since the ANWR was created, there has been a fight over opening the 1002 area for drilling.

The political fight in Washington, DC rises and falls every few years. Meanwhile, almost like clockwork, tens of thousands of Porcupine caribou converge on the 1002 area once a year to give birth to their calves.

Studies show that oil drilling in the calving grounds could have terrible impacts on the caribou and numerous other Arctic animals.

But that’s not all. Drilling would also endanger the Gwich’in, Native people whose territory overlaps with the Wildlife Refuge. The Gwich’in culture, which, needless to say, long predates the oil interests intent on expanding into the 1002 area, is tightly connected to the caribou. For countless generations, Gwich’in have hunted caribou for meat and other uses. If the calving grounds were ever developed, it would impact the caribou, numerous other animals and the Gwich’in Nation.

Lenny Kohm, the focus of Defending the Arctic Refuge, entered the political fight in the late 1980s.

Kohm, a jazz drummer turned photographer and activist, shot most of the images used in an influential slideshow presentation designed to convince Americans of the importance of protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. At the time the slideshow was created, Kohm lived on The Art Farm, an artist cooperative outside of the city of Sonoma.

After tiring of life as a touring musician, Kohm became radicalized on a trip to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. When he returned to California, he was determined to find out how to help save the refuge from oil drilling.

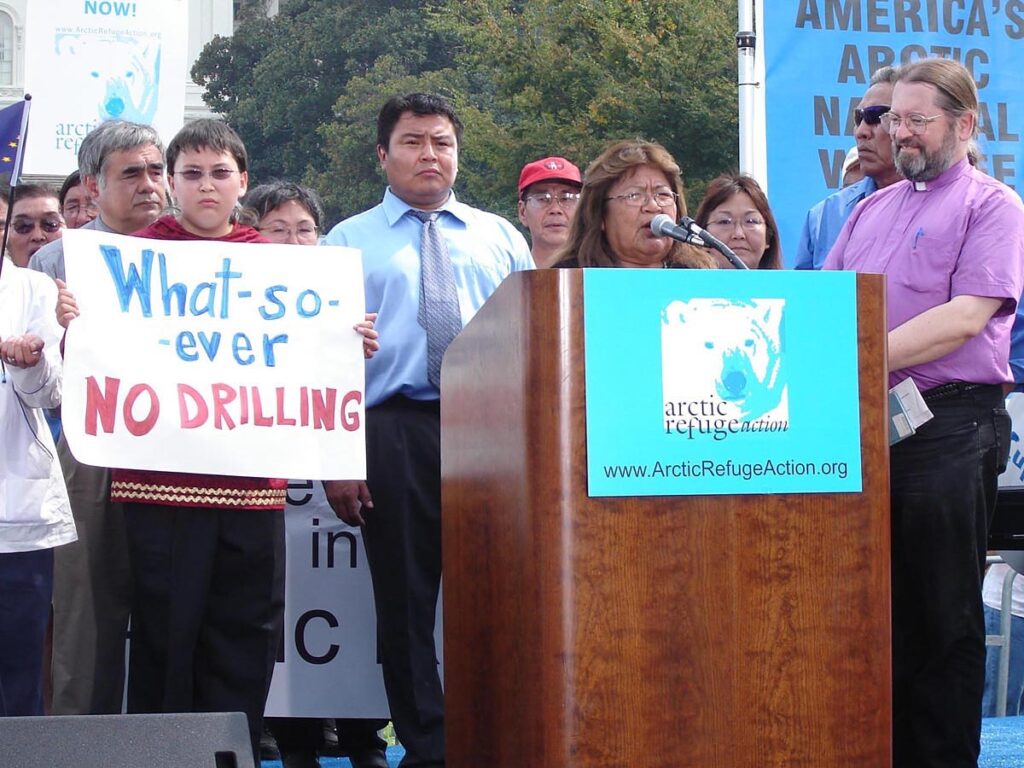

As part of this effort, Kohm helped produce a slide show presentation, titled The Last Great Wilderness, with a group named the Sonoma Coalition for the Arctic Refuge. The show was presented using two synchronized slide projectors, fading between images in time with voiceovers and songs. Over the next decade, Kohm, other environmental activists and members of the Gwich’in nation presented The Last Great Wilderness hundreds of times in towns and cities throughout the country in an effort to influence politics from the ground up, at a time when national environmental organizations were prioritizing Washington lobbyists.

Many of the themes evoked in the slideshow still ring true today. The presentation reflects on climate change, America’s endless drive for resource extraction at home and abroad, the sense of powerlessness felt by those trying to resist these expansionary forces and the wisdom of Indigenous cultures.

The state of environmentalism in the 1980s makes the show an intriguing and important historical relic.

At the time, mainstream American environmentalists often used narratives largely focused on the need to maintain the Refuge as a pristine piece of nature, untouched by humans. The Sonoma Coalition’s slideshow and other advocacy efforts helped to center the centuries-old relationship between the Gwich’in and the Porcupine caribou in the debate over drilling in the refuge.

“Instead of trying to salvage a ‘sample of the pioneer frontier,’ a central myth of frontier colonialism, Lenny and the Gwich’in spokespeople framed refuge protection in terms of Indigenous cultural survival,” Dunaway writes.

Of course, not all credit should go to Kohm for this shift or the successes of the broader anti-drilling campaign. Before and after Kohm picked up the cause, the Gwich’in engaged in their own advocacy efforts, and the debate around Arctic drilling may have come to focus on Indigenous rights even if Kohm had not appeared. Still, Indigenous people quoted by Dunaway credit Kohm and the slideshow with playing a meaningful role in the effort to prevent drilling in the Arctic Refuge in partnership with Gwich’in advocates.

“Lenny was not a savior single-handedly rescuing the Arctic. He knew that true power came only from organizing and mobilizing collective voices,” Dunaway writes.

In recent years, many American environmental organizations have shifted focus to environmental equity and Indigenous rights, rather than focusing on preserving pristine wilderness.

Meanwhile, the debate over drilling in the 1002 area continues to crop up in the national discourse every few years. In 2017, Republicans successfully passed legislation to open the contested area to drilling as part of the $1.5 trillion tax cut package. Celebrating the victory, Trump bragged that he had accomplished what several of his Republican predecessors had aspired to accomplish during their time in office.

Over the next few years, the Trump administration cut one corner after another in their effort to auction off the oil rights before the end of Trump’s first term.

On Jan. 6, 2021, the auction occurred. But, from the perspective of the oil-backers, it was an unmistakable dud. The sale raised only $14.4 million in revenue for taxpayers from three bidders, in an auction Republicans promised would bring in roughly $1 billion.

The prevailing theory seems to be that changes in the energy markets combined with sustained pressure from activists on business interests and politicians, helped to cool the economic interest which drilling backers hyped for decades. Is that the end of the story?

Not quite. As always, the cycle of American politics continues. After Russia invaded Ukraine, there were once again calls, citing National Security, to increase oil drilling domestically, including in the Arctic Refuge.

Joe Biden’s administration opposes drilling in the 1002 area, but has approved drilling permits on other public lands at an astounding rate.

Once again, a quote from The Last Great Wilderness seems relevant: “Will we be more secure when we’ve developed our last oil field? When through our addiction to the use of fossil fuels, we’ve added more to the dangerous global warming trend?”