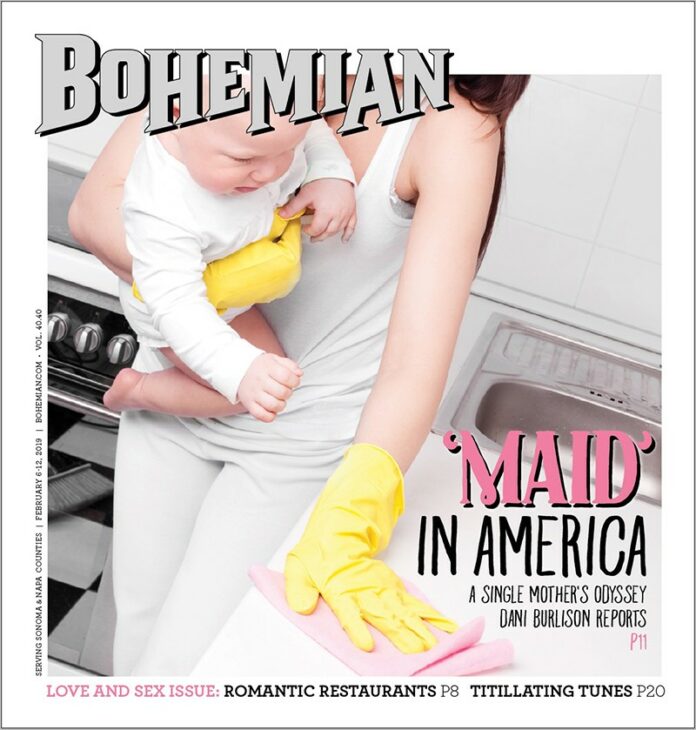

The weight of living as a low-income single mother can be crushing. Surviving below the poverty line (i.e., no savings to dip into or family members to borrow money from) can mean spending every waking second hustling to simply scrape by.

The type of soul-sucking poverty that one can’t see a way out of—drinking coffee to quell hunger because you have to choose between feeding yourself or feeding your kid—can feel like a constantly shifting puzzle, never quite fully constructed and constantly at risk of collapse. Each bit of income, every expense, and each spare moment, is held in a fine balance. Faced with an unexpected expense like a car repair can mean going without meals, losing gas money and therefore missing more desperately needed work shifts, and risking water or electricity being shut off.

It can feel like running uphill through mud. In the dark. With no cash to buy batteries for your flashlight.

In Maid: Hard Work, Low Pay and a Mother’s Will to Survive (Hachette Books), Stephanie Land carries readers through the exhaustion of living below the poverty line. The memoir paints a candid picture of parenting while poor, and the stigma of being a public-assistance recipient in “pull up your bootstraps” America.

“People who have lived in poverty or very low income, they’re always scrambling for the next thing,” says Land by phone from her home in Montana. “I think it’s just ingrained in you to not really relax, because you’re always looking at the next thing and what you can do to keep the income coming in.”

And Land certainly knows a thing or two about scrambling. “As a poor person, I was not accustomed to looking past the month, week, or sometimes hour. I compartmentalized my life in the same way I cleaned every room of every house—left to right, top to bottom,” she writes.

As a young mother, Land fled an abusive relationship and found herself and her infant daughter Mia in a homeless shelter. From there she trudged along a rocky maze of transitional housing, community college, countless mounds of paperwork for public assistance like SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, what used to be known as “food stamps”), low-income housing and a stint as a landscaper before arriving in a drafty studio apartment that she paid for by cleaning houses.

Land first published a story about her house-cleaning experiences for Vox in 2015. The viral essay, “I Spent 2 Years Cleaning Houses. What I Saw Makes Me Never Want to Be Rich,” eventually led to a proposal for Maid. The book takes a deeper look at the issues addressed in the Vox story, and chronicles Land’s long hours of schlepping mop buckets and cleaning supplies into the homes of relatively wealthy strangers.

Land describes the sometimes eerie sense that settles across an empty home that maids visit for deep cleanings. The owners know little to nothing about the cleaners; many didn’t even know Land’s name. She was like a ghost to them. Yet, after spending up to three hours alone in the homes on a regular basis—scrubbing bodily fluids off of bathroom surfaces, tucking sheets into beds and transporting trash to outdoor bins—Land developed an intimate understanding of who the homeowners were and what their lives were like.

She knew how much alcohol they drank and where they stashed their cartons of cigarettes. She knew the types of pornographic magazines they preferred. She knew about their physical and mental-health issues from the various prescription pill bottles lined up in medicine cabinets and clustered on bathroom counters. She knew about their relationships and how much they spent on groceries and household items.

Housecleaning work is physically and sometimes emotionally taxing—there is a reason people hire help to do the cleaning for them: it is really hard work—especially for domestic workers with chronic health issues.

Though I’d never tell my manager about it, nerve damage in my spine prevented me from gripping a sponge or brush with my right, dominant hand. I’d had scoliosis, a condition that made the spine curve from side to side, since I was a kid, but recently due to the cleaning work it had pinched a nerve that went down to my right arm. . . . My left hand took over whenever the right one got too tired, but in those first months of six-hour days, when I got home I could barely hold a dinner plate or carry a bag of groceries.

Most people don’t realize that after paying for a cleaning service, workers themselves often receive close to minimum wage for their labor. Land’s first cleaning jobs in 2009 earned her $8.55 to $10 an hour. For cleaners with only one income-earner at home (and children to support), this clearly isn’t enough to live on; low-wage earners often need the safety net of public assistance to make ends meet.

Yet public assistance can be problematic. Contrary to popular myth, being on public assistance is no easy ride and can be discontinued if paperwork isn’t completed accurately, or if monthly income exceeds the allowed amount—even by a few dollars. Land describes that at one point she was on seven types of assistance, from a low-income energy bill program to low-income housing. The requirements and piles of paperwork were daunting.

And yet despite receiving various sources of government support to fill in financial gaps while working up to 25 hours a week (she wasn’t paid for travel time or for washing her cleaning rags at home), Land still barely kept her head above water. The stigma of her circumstances also brought an unwavering sense of shame; spending a few extra dollars treating herself and her daughter to a meal at a restaurant on a rare occasion made her feel reckless; allowing herself any time to relax evoked guilt and anxiety.

“I think the legislators and the general voting public are obsessed with whether or not poor people work for their benefits, and so I think a lot of the paperwork that’s required is just proving not only how poor you are, but proving how much you do work,” says Land. “Even if you do prove it, you have to prove it even more, on a sometimes monthly basis, and it’s degrading. I don’t think people really understand that part of it either. There’re a lot of things about the system that work against poor people and just make it harder for them.”

[page]

Land points to the proposed changes to the Farm Bill as an example of increased requirements for SNAP benefits. Although Congress voted for an $867 billion Farm Bill in December, just a week later the Trump administration declared that it would continue seeking more stringent regulations on who can receive SNAP benefits, including increasing work requirements for older workers between ages 49 and 59, and for workers with young children ages 6 to 12. The proposed changes would affect over 1 million households nationwide.

The perpetual fear of living with financial instability and working hard—while constantly proving how hard she worked—wasn’t the only thing that weighed on Land. In Maid, she opens up about living in a state of shame for receiving benefits, and the stereotypes and resentment often projected on to poor people, even by friends. She describes people commenting with snide voices, “You’re welcome” when they’d spot her using food stamps at the checkout line.

“It seemed like certain members of society looked for opportunities to judge or scold poor people for what they felt we didn’t deserve,” Land writes. “They’d see a person buying fancy meats with an EBT card and use that as evidence for their theory that everyone on food stamps did the same.”

For many, the mere idea of public assistance certainly evokes stereotypes and raises questions about who deserves help (and for those that are deemed worthy of help, how much support they deserve also comes into question). And of course, there’s a classist assumption that all moms use their food stamps strictly to buy junk food for their kids, which Land—unapologetically—said she did on special occasions.

“I used to do that for Christmas. I bought candy with food stamps,” she says. “I used to buy treats for my kid because that was all I could get her. I couldn’t afford to get her a toy or a lot of stuff, but I could buy her a piece of candy with food stamps. To me, I’m giving my child a moment of joy.”

In addition to the stress of financial insecurity and the grueling, often degrading experience of scrubbing other people’s toilets that Land addresses in Maid, she offers a glimpse into the isolation she often felt raising Mia alone:

Sometimes just walking behind a two-parent family on a sidewalk could trigger shame from being alone. I zeroed in on them—dressed in clothes I could never afford, diaper bag carefully packed into an expensive jogger stroller. Those moms could say things that I never could: “Honey, could you take this?” or “Here, can you hold her for a second?” The child could go from one parent’s arms to the other’s.

Land eventually left Washington and completed her English degree at University of Montana’s creative writing program. She continued cleaning houses until her last year in school, when her second daughter was just a baby. Since graduation, her career path has taken an upward swing; in addition to getting Maid published, Land now works as a full-time writer.

She’s been a fellow at Center for Community Change and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, and has published in the New York Times, the Washington Post, The Guardian, Salon, The Nation and elsewhere.

“I felt like I had to hold myself accountable to the degree, and I stubbornly kept myself to that—not that there’s anything wrong with side gigs or having to go back into cleaning,” she says.

According to a report issued by the U.S. Census Bureau in September 2018, there are 39.7 million people living in poverty across the country, and based on the Bureau of Labor and Statistics, there are over 900,000 house cleaners nationwide in 2017, earning an average of $11 per hour. Maid takes these impersonal statistics and the topic of income inequality and gives them a face. Her voice represents millions who are attempting to survive on low wages—and reveals the truth of what it’s like for so many single parents struggling to get by, one day at a time:

I would hear the same thing again and again: “I don’t know how you do it.” When their husbands went out of town or worked late all the time, they’d say, “I don’t know how you do it,” shaking their heads, and I always tried not to react. I wanted to tell them those hours without your husband aren’t even close to replicating what it is like to be a single parent, but I let them believe it did. Arguing with them would reveal too much about myself, and I was never out to get anyone’s sympathy. Besides, they couldn’t know unless they felt the weight of poverty themselves. The desperation of pushing through because it was the only option.

Land says her book is succeeding, in part because “people are more apt to listen to someone who is on the other side and who is a success story, and I cringe at that, because the system is not a successful system.”

In a perfect world, Maid would become required reading in schools across the country. In the very least, it should evoke compassion and stir empathy in people who have never walked in Land’s shoes. And hopefully that empathy can lead to big changes in how poor people are treated in America.

“I’m really hoping that my book changes the way people think about the lower classes and working classes,” she says, “and I’m hoping it increases their view of humanity, and gives them more compassion. I hope it sets up the stage for more books like mine to come out, from women of color and from more people in the margins.

“I think the world should be ready to hear from angry poor people.”