I might never have been born if it weren’t for one of my favorite films.

Let me explain.

My parents worked together in San Francisco for a few years before dating in secret to avoid office gossip. They watched their first film together as a couple in May, 1979, at a theater in Corte Madera. The lead actress, a nobody, had only one prior credit—as an extra in Annie Hall. The simple sets included bomber-plane parts left over from World War II, Christmas lights and cathode-ray television sets. The even-simpler plot had been repeated a million times before: a spaceship crew, led by Sigourney Weaver, encounters a monster and fights for survival.

But the monster my parents—and millions of other moviegoers—first met in 1979 never left our collective unconscious.

The Alien

As Alien celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, I’ve thought a lot about both the movie and the creature that enthralled and terrified me as a kid. After three sequels, two prequels and two tie-ins with the Predator franchise, it’s hard for viewers to remember pre-1979 sci-fi aliens; the Alien changed the genre forever.

Beginning with H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, just about every alien depicted in literature, film and television possessed either an intelligence or motivation people understood. Possessed with “intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic,” Wells’ Martians “regarded earth with envious eyes.” In the following decades, these and other “bad” aliens were either highly intelligent menaces or zoo creatures on the loose.

The Alien, however, was completely different—primal, dangerous and, as science officer Ash states near the film’s end, pure. It didn’t even need eyes to pick off the Nostromo‘s crew one by one.

The Alien possessed a Freudian nightmare of a lifecycle that combined rape, birth and a whole lotta phallic imagery—it wasn’t what hid in the shadows, it was the shadows. It wasn’t something to fear, it was fear.

The Alien as we know and love it resulted from two problems screenwriter and USC grad Dan O’Bannon encountered while writing the screenplay’s first draft. Firstly, in similar films, the alien always entered the spacecraft through a ridiculous plot device such as someone forgetting to close a hatch.

Secondly, O’Bannon received a diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease, a condition that led to his death in 2009. Feeling as if your guts are tearing apart from the inside out is one of Crohn’s main symptoms.

So, O’Bannon wondered, what if the creature entered the ship inside someone and then burst its way out of them?

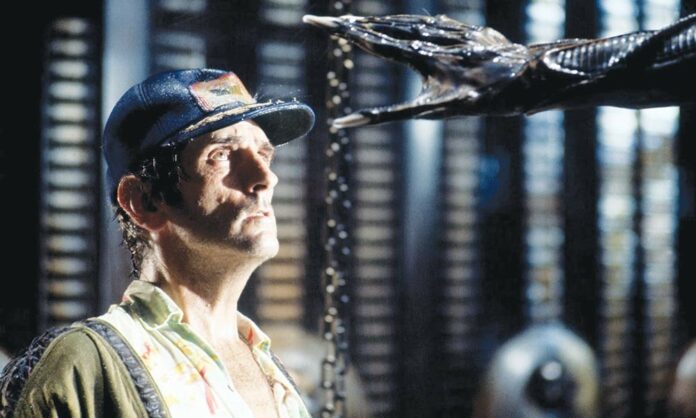

“The thing emerges” are three words from the Alien script that describe the day the film’s cast entered the set—the spaceship Nostromo‘s dining room—and found the cameras wrapped in plastic and the air heavy with the stench of animal blood and formaldehyde. Two puppeteers, two technicians manning plungers full of all that nasty fluid, and most of actor John Hurt’s body—only his arms and head were visible—hid beneath the dining room table. The rest of his “body” above the table consisted of dummy legs and a chest cavity filled to the brim with rotting cow parts and the “chestburster” puppet.

The scene, from the chestburster’s bloody entrance to its now-famous scurry off-set, lasts only 25 seconds. But those 25 seconds are a master class in how to make actors perform genuinely in spite of them knowing everything that is going to happen well in advance. Veronica Cartwright, no stranger to horror since her days as a child actor in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, let out a genuine scream of mixed horror and disgust.

And from that iconic moment on, monster movies, sci-fi movies and horror movies were never the same.

From Oct. 13-16, North Bay cinemas celebrate the 40th anniversary of Alien with special showings: Century Napa Valley (195 Gasser Drive, Napa), San Rafael Regency 6 (280 Smith Ranch Road, San Rafael) and The Clover (121 E. First Street, Cloverdale). Reserve your tickets online by visiting Fathom Events.

If you’re one of the few people who never saw Alien, I envy you. And if you can’t wait until later this month to view it on the big screen, do yourself a favor and watch it in a pitch-black room late at night with the sound turned way up. It’s an old movie, you might tell yourself. CGI didn’t even exist back then. How could it be scary?

I won’t lie to you about your chances of surviving the ordeal, but . . . you have my sympathies.