At first it was just Mike.

At about 11:30pm on Oct. 8, KSRO radio producer and engineer Mike DeWald was finishing a game of hockey at Snoopy’s Home Ice in Santa Rosa when he smelled smoke. Maybe the Zamboni was overheating, he thought.

Heading for his home in Rohnert Park, DeWald’s phone began to light up with messages about a fast-moving wildfire headed from Calistoga to Santa Rosa down Mark West Springs Road. He wasn’t going home now. He turned around in Cotati and headed to the radio station in Santa Rosa. By the time he passed the Sonoma County Fairgrounds on Highway 12, he could see fire illuminating he night sky in the east. It looked like “the gates of hell opening up on the horizon,” he says.

When DeWald arrived at the KSRO studio on Neotomas Avenue, he was alone. DeWald is the producer of The Drive with Steve Jaxon, from 3pm to 6pm, and works behind the scenes. But he was ready to go on the air to report on the fires, the scale of which he did not yet comprehend.

“I said, ‘I guess I’m going to have to do this.’ Just as I was about to do that, I saw movement in the parking lot. I thought, ‘That’s strange.’ And a few seconds later, Pat Kerrigan walked in.”

DeWald quickly learned that Kerrigan, KSRO’s 6–9am news anchor, had just been evacuated from her home in Kenwood. She was there with her wife and dog.

“She said something like, ‘Are you ready for this? Here we go.'”

What followed in the chaotic, early hours of Oct. 9, as the fire lay waste to thousands of homes and displaced some 100,000 people, was an extraordinary moment in Sonoma County. Just after midnight, DeWald broke in on the syndicated broadcast of Coast to Coast AM, a talk show about UFOs, Bigfoot and all things paranormal, and Kerrigan began to report the little she knew about the fires.

Fifteen minutes later, Michelle Marques, a former news reporter and host of a community affairs show on KSRO, arrived. She lives in middle Rincon Valley and awoke to the smell of smoke the same moment DeWald texted her a photo of the fire with a message that it was burning from Calistoga to Santa Rosa. After alerting her roommate, Marques grabbed her passport, 2016 taxes, sketchbook, toothbrush and two pairs of underwear and headed out the door. What she saw terrified her. Fire was visible to the south, and to the north she saw Fountaingrove ablaze.

“It was glowing red,” Marques says, “but bright like the sun was coming up. There were huge visible flames coming up along the ridge.”

Like DeWald and Kerrigan, Marques knew she had to get to work. She drove through hot blowing wind, debris and smoke on her Vespa scooter, her only vehicle. “I was really terrified. I think I was hyperventilating.”

DeWald, 30, started at KRSO 13 years ago as an intern. Because of his nine years scheduling guests for The Drive with Steve Jaxon, DeWald’s cell phone holds numbers to a who’s who of Sonoma County.

“I don’t know everyone, but I know how to reach everyone,” he says.

He was soon lining up calls for Kerrigan and Marques with public officials, photographers and others with on-the-ground information about the fire.

It didn’t take long for the trio to comprehend how large and destructive the fires were. For DeWald, that moment came when Press Democrat photographer Kent Porter called in about 7am to report on the destruction he had seen in the Fountaingrove area.

“He was describing these landmarks that weren’t there anymore,” DeWald says. “‘This is gone. This is gone. This is gone.’ It was the first description of where the fire had reached near downtown. It was a sobering moment in the studio where we realized the fire was here and it had hit us.”

The seat-of-the-pants broadcast built on itself. The more public officials and others with information about the fire appeared on the air, the more others turned to the station to get the word out.

“It began on the fly and remained on the fly,” Kerrigan says. “Most of the preparation involved somebody handing me a piece of paper with a note scrawled on it so I knew who I was talking to.”

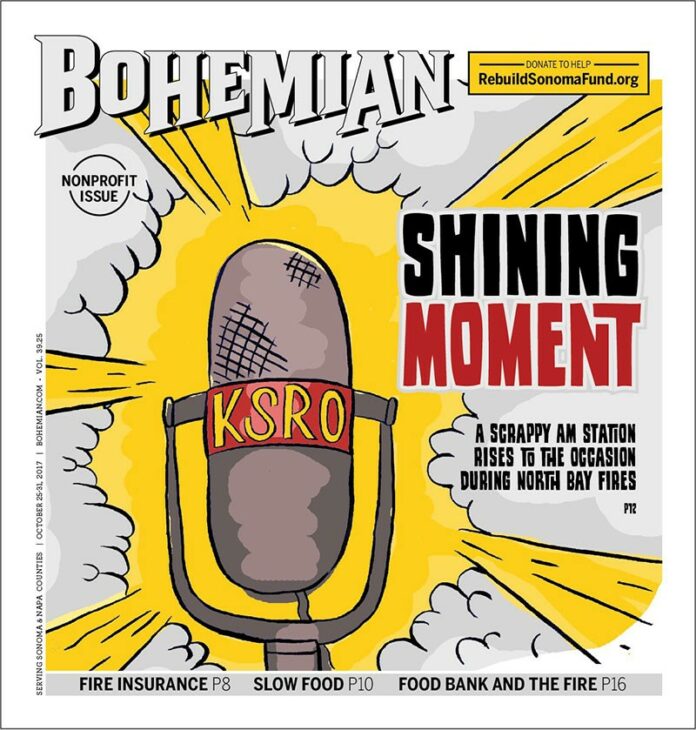

The station become a conduit of information, receiving news and broadcasting it in the same moment. In a crowded, highly fractured media landscape, frumpy AM radio emerged as the most essential source of information about the fires. Not bad for an 80-year-old radio station using technology that dates back to the late 19th century.

Kerrigan and Marques were on air until noon—for about 12 hours. DeWald pulled a 19-hour day behind the board; the next day was 17 hours.

With regular programming out the window, Steve Garner, Steve Jaxon, Heather Black and others stepped in to hold down the mic. Kerrigan, whose smoky voice, at once authoritative and comforting, is now inextricably linked to the fires, doesn’t know how she has a voice left at all.

“It doesn’t make sense. I guess that’s the way it’s supposed to be right now,” Kerrigan says.

Soon, everyone at KSRO was working long hours, answering phones, lining up guests, posting to Facebook and relieving DeWald, Kerrigan and Marques. And it continued in the days that followed before anyone could take a breath. The station went several days before they aired a commercial.

“It was like a telethon in the studio,” DeWald says.

KSRO became the voice of Sonoma County in part because early on there was no one else able to fill that role. Since the fires damaged cell towers, knocked out internet service and disabled Comcast cable for many hours, KSRO 1350-AM became the first and best source for information. The station, part of Amaturo Sonoma Media, also simulcast on its four sister FM stations. KSRO was omnipresent. Unlike FM transmitters, which use line of sight to broadcast their signal and must be erected on mountaintops and ridges, AM transmitters are located in lowlands, because AM radio waves travel near the ground. KSRO’s transmitter was well out of the path of the fire on Stony Point Road near Highway 12. The station is required by law to drop its signal from 5,000 watts to 1,000 at night, except in cases of emergency.

“That’s what we did,” says Michael O’Shea, Amaturo Sonoma Media president. “We broadcast at full power 24/7.”

[page]

By 3am, the station was getting crowded, as many of KSRO’s employees were evacuated. No one knew how long they would be safe, because the studio is located at the mouth of Bennett Valley, an area that would later be evacuated. O’Shea fled his Rincon Valley home and arrived at the station about 3:15am. He took a photograph from the station’s parking lot that showed how close the fire was. During one broadcast in the first week of the fires, Jaxon had to dash out to get his dogs when evacuation of his Bennett Valley neighborhood was announced.

In the early days of the fire, there was no time to plan the broadcasts because there was so much happening, so much news to report. “It was just, keep it going and keep talking to people,” O’Shea says. He adds that Kerrigan was the best talker of all.

“I cannot offer any higher accolades to anybody,” O’Shea says. “She was our quarterback.”

Kerrigan has only been the news anchor at KSRO for a year, but she clearly rose to the occasion.

“I’m old-school radio,” she says. “I think that’s why radio stations were created: to be of service to their community, and this is the perfect example of it.”

DeWald, during the long hours in the studio (which he calls a “a 30-by-30 box”), worked to maintain mental focus. He likens his job of producer to that of a conductor.

“Whoever is on the air plays off of me. I have to keep calm as a middle point between things happening in the newsroom and things happening on the air. Because if that chain breaks, then the sound on air becomes more chaotic.”

And chaos is not what people needed to hear. Local and state officials have been profuse in their appreciation of KSRO’s coverage.

“I want to thank KSRO for keeping the community apprised from top to bottom,” said State Sen. Bill Dodd in an interview on Monday with Kerrigan.

Like Kerrigan, Sonoma County Sheriff Rob Giordano became a household name in the wake of the fire and a regular on KSRO.

“They did quite the job,” he said. “They just kept covering everything and talking to everybody.”

In a disaster, cell phone and internet service can be unreliable. But not radio, he said.

“It’s old technology and it works great.”

While he spent most of his time in the studio, DeWald went to Coffey Park the fourth day of the fires to report from the field, a first for him. The photographs he saw and interviews he heard did not prepare him for the devastation.

“When you actually stand in the center of Coffey Park,” DeWald says, “you see it’s just pieces of everyone’s life sitting in front of you in this area of desolation. To actually stand there and see it was just a really heavy moment.”

As the fire entered its second week, staff shifts began to normalize. DeWald was able to take time off to see a Shark’s game. Marques visited a friend in Petaluma and played Legos with her four-year-old daughter, a welcome change of pace. As of Friday, Kerrigan had not had a day off, but she was planning a break.

Even on her time off, Marques says she was still texting DeWald about the fire, processing what she’d seen and heard. “You’re terrified and you can’t really rest.”

During her second day on the job, the events of the fire got to her.

“I didn’t cry the first day,” Marques says, “but I did have to stop a couple of times the second day to just cry, and I couldn’t be on the air because it was awful. We were finding out how many people had died.”

When he first got home, DeWald said he needed time to decompress and reflect on what he had seen and heard.

“It weighs on you so much, but in the heat of it, it doesn’t hit you. But in the quiet by yourself, all these things you’ve heard come back to you. It’s a powerful thing.”

As firefighters gained control of the blazes last week, Santa Rosa residents expressed their appreciation to Cal Fire, the Santa Rosa Fire Department, the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office, PG&E—and KSRO. Banners were hung from freeway overpasses and placards went up on light poles. The praise is not something Marques is comfortable with, especially since there are people still unaccounted for. “I don’t feel that’s appropriate. We were just doing our job.”

DeWald was taken aback by the banners.

“We don’t belong with those names. We weren’t running into the fires, but seeing that did choke me up a little bit. It made me realize what we did had an impact.”

For Kerrigan, who has been a Sonoma County broadcaster since 1980, she appreciates the praise but hasn’t been able to pay much attention to it. She just returned home home last week.

“I’m honored by it,” she says. “I hope one day to be able to sit down with all of that, but I don’t know when it will be.”

The fires are all but out as the cleanup and long road to recovery begins. I knew things were getting back to normal when I tuned into KSRO last week and Coast to Coast was back on air. The show focused on some apparently compelling photos of an alien that had crash-landed in Roswell, Ariz., in 1947. Lamentably, the bilious Laura Ingraham is back on the air, too, a study in contrast to the goodwill on display in the North Bay. Syndicated programming had been suspended during the early days of the fire.

Monday, I heard a commercial from a prospecting law firm looking to sign up clients interested in suing PG&E, even though the cause of the fires has yet to be determined. Life goes on. But like the fire, KSRO’s role won’t soon be forgotten.

“The story was and is maybe the biggest thing that will ever happen to us as individuals and a community,” Kerrigan says. “It’s been the kind of radio people like me dream of—except for the circumstance of it.

“If it weren’t for all this death and destruction it would be a great couple of weeks of radio.”