Over the past year, the U.S. has experienced a surge in labor organizing.

After decades of decline in union participation and real wages, workers at Amazon, Starbucks, REI and numerous other companies big and small have voted to form unions or participated in other forms of labor actions, often in the face of fierce resistance. The surge in labor action has been accompanied by historic popularity of unions, with 71% of respondents to an August Gallup poll voicing approval for unions, the highest rate since 1965.

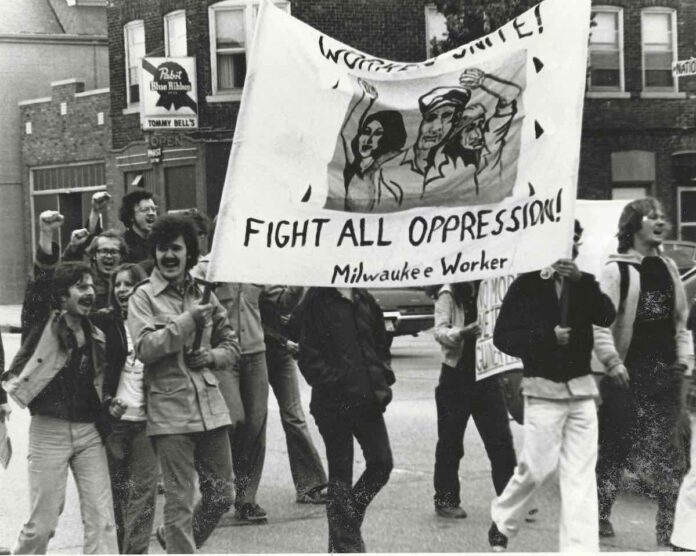

This makes it a fitting time for the publication of Sonoma County resident Jonathan Melrod’s new memoir, ‘Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class Struggle.’ The book centers on Melrod’s 13-year effort to “harness working class militancy and jump start a revolution on the shop floor of the American Motors’ auto assembly plant.”

After cutting his teeth as a college radical, Melrod takes a union job at an American Motors’ factory and begins to make trouble. Melrod and his colleagues publish a radical workers’ newsletter titled ‘Fighting Times,’ lead numerous strikes and walkouts, and, ultimately, face down the American Motors-funded defamation lawsuit against the newsletter’s editors.

Much has changed in the world since the 1970s, but Melrod’s memoir, jam-packed with stories from the front lines, makes for an entertaining, educational and timely read. An excerpt from the book follows.

‘Fighting Times,’ published by PM Press, will be available in stores and online on Sept. 27. Melrod will speak at the Sebastopol Copperfield’s Books on Thursday, Oct. 6 at 7pm. The event is free, but RSVPing online is recommended. —Will Carruthers, News Editor

—

The ups and downs in auto, based largely on consumers’ preference for this or that model, meant assembly plants went through cycles of layoffs and expanded employment. The Kenosha American Motors’ plant saw a mass hiring of young workers who were rebellious and not cowed by the company or the union. And dissatisfaction with Department 838 long-term chief steward Russ Gillette reached a tipping point.

Gillette’s name did not even appear on the vote tally for the 1979 stewards’ election. I can no longer recall if Gillette went on sick leave or chose not to run, but he’d had enough. Gillette’s departure fractured his clique’s standing.

When election results were posted, I had placed second with 132 votes, topped only by Peggy Applegate, the only woman steward.

For the election, I organized a team of fresh, young activists, loosely affiliated with the UWO United Workers Organization, to run for stewards’ positions. Of the twelve positions, four of our candidates won in addition to me. The most significant victory accrued to Jimmy Graham as the first steward of color in Department 838.

The vote totals presented a conundrum. Kojak, my former Milwaukee head steward, was elected and announced his intent to run for chief. Jim Gathings, who had placed behind me with 127 votes, also announced he was running for chief.

Gathings hailed from the 838 old school and was a pickup-driving, tobacco-chewing, self-proclaimed cowboy with an inflated belly hanging over a large turquoise belt buckle. Like quite a few in the plant, Gathings’s other job was tending his farm, and he also held a semiskilled repair job.

Rather than run for chief, I opted to let Kojak challenge Gathings, planning to devote the year to teaching UWO-affiliated candidates how to become effective union reps. I could be patient, as I was down for the long haul.

Gathings, still able to rally Gillette’s base, beat Kojak, who had appealed primarily to former Milwaukee guys who had previously transferred to the Kenosha plant.

By virtue of being chief, Gathings gained entitlement to overtime if any worker in 838 on his shift was scheduled to work overtime. Gathings sucked up every minute of overtime, providing a fat paycheck but also inextricably tying him to management, as a piglet latched to its mother’s teat.

While daily interaction between Gathings and me remained superficially cordial, underlying tension tinged our every conversation. Our clashing outlooks surfaced with venom one Monday morning. Heading for nine thirty break, I ran into an animated scrum of young department members. “Melrod, did you hear? Gathings told Cathy (the steward) she shouldn’t be kissin’ on a nigger. It’s way fucked up.”

A group of Department 838 folks had been partying behind Madore’s bar after work the preceding Friday. Cathy and Jessie Sewell, a Black worker, exchanged a kiss. A kiss between a Black guy and a white woman—nothing more.

Nevertheless, the incident was stoking a brushfire, and I needed to get the facts down.

Jessie worked one station up the line. I had spent hours hanging with Jessie, and other regulars, behind Madore’s, drinking pints. Jessie was also a solid Fighting Times ally.

As soon as I could get a utility worker to relieve me, I checked in with Cathy. She was a new steward, and I had been mentoring her to adopt a more confrontational stance with management.

“Hey, Cathy—heard some bullshit’s going down with Gathings. He’s been running his mouth spouting racist shit about Jessie and you. What’s up?”

“Jon, I’m afraid for this to turn into a big public incident. I don’t want Gathings coming down on me.”

“I hear you, Cathy, and I get it, but Gathings got no right to talk about you. Just because he’s chief doesn’t mean he’s got any business getting in your face about who you want to party with or who you kiss! That’s sexist, racist b.s. Plus you’re a steward now, and you need to set an example of good unionism. Gathings, and I don’t care if he’s chief, can’t go around mouthing racist bullshit. He’s gotta treat you like a grown woman, with respect. Gathings is way out of line.”

“Jon, please let me think about it.”

“Cathy, it’s not you causing trouble—it’s Gathings. But if you feel like it’s over and want to drop it, I’m cool.”

By lunch, the whole department buzzed. Blacks were outraged. Many grabbed me, wanting to know what could be done. In the past, a racist incident might have sparked an angry reaction and then fade; not this time, I thought.

As department chair, I put the incident on the agenda. I met with the other stewards who had run with me, and we discussed our obligation to address racism at the department meeting. Graham took a strong position, as he had previously complained about Gathings’s shit attitude toward Blacks.

With increasing intensity, word spread of a confrontation going down. Black people, many of whom had never thought of attending a department union meeting, beat the drum to call out Gathings. Similarly, many younger whites took offense at Gathings’s behavior.

I needed to get Jessie onboard. “Hey, bro. Que pasa? What’s up with this Gathings bullshit? He’s been mouthing some nasty name calling ’bout you.”

A pained look crossed Jessie’s face, a stark contrast to his usual clowning demeanor. He looked hurt and embarrassed. Even though he was free and equal to Gathings, he felt stuck taking shit from a self-proclaimed cowboy whose primary reason for being chief was greed.

“Melrod, what I’m gonna do? Ain’t nobody care. Gathings is chief.”

“Fuck that, bro! We got our guys—Ernie, your main man—and Pedro got the Mexicans. We got the Blacks who are tired of racist shit. We got the young people and the Fighting Times people. We don’t gotta let this slide. We gotta jack Gathings up. It’s on the agenda for the department meeting. Ya with me?”

Tension on the floor ratcheted up. I noticed Gathings huddling with his white repair buddies (there being only one Black 838 repair worker).

It might have been the largest department meeting in 838’s history. I looked out, and many of our people had shown up, particularly Blacks. I also noticed a gaggle of repair workers and a smattering of old-school, conservative types who I assumed had attended at Gathings’s urging. I called the meeting to order. Old business first.

“Hey, Melrod, we ain’t here for no old business. We’re here ’bout what Gathings said about Jessie.”

“All right then, new business.”

I called an audible, turning toward Gathings sitting next to me, a rather uncomfortable seating plan.

“Jim, I believe folks want to hear about the incident with Jessie and Cathy that involves you.”

“Yeah, yeah. I wasn’t serious. I was just joking ’bout what I said. It ain’t that big a deal.”

I’d been watching Jessie; his face tightened. He sat for a few uncomfortable seconds. I waited for the slightest movement of his hand and immediately called on him before he put it back down.

“I been hearing Gathings has been talking about me. He got no business talkin’ about me being Black or any color.”

Gathings, in a voice barely audible, said, “Yeah, I shouldn’ta said nottin’.” This can’t be the end of it, I thought. This is too important.

I saw Graham’s hand. “Jimmy.”

“That ain’t an acceptable apology. If Gathings is chief, he can’t be talkin’ racist shit about no one. The union is about us all. The union’s strong only if we are together. I never want to hear no one using language calling a brother or sister that fucked-up word! You hear me, Gathings?”

“I didn’t mean no harm.”

“Gathings—ain’t the point. Your talk is harmful. You got no right talkin’ about Jessie or Cathy. Ain’t your business.”

For the first time, Blacks in the department stood their ground and made their voices heard, not just about the incident with Jessie and Cathy but also how they felt ignored and disregarded by the union. Gathings had been the catalyst, but the discussion was cathartic for airing long-held grievances about discriminatory treatment and favoritism—from both management and union.

Somebody tapped a keg, and I noticed people filling big red cups with beer. Beer on an empty stomach, particularly as tempers flared, didn’t portend well.

“I think we covered the agenda, but I have a few comments. First off, I want to thank the huge turnout. Anyone who’s got something to say can say it here. Having said that—the bottom line is there’s no place for racism in our union, no way, no how! Adjourned.”

Steward John Leyendecker and I chatted in the beer line. Beers in hand, we talked. In the drift of the crowd, we ended up across from Gathings and another old-school steward. You could cut the tension.

Gathings stared at me with palpable scorn. We couldn’t have come from two more different worlds. I had left the East Coast for college in Madison. He had stayed on the farm and gone to work young at AMC. He chewed tobacco. I smoked pot. His proudest moment was when his daughter placed first at 4-H for her cow, and I had come from Milwaukee and uprooted his world, in his eyes.

“Hey, Melrod. I don’t like what you been saying about me.”

“Only talkin’ truth, Gathings. You had a chance to call me out but didn’t. I don’t like hearing how you dissed my partner Jessie. I can’t change your thinking, but we all got to act right in the union.”

“Fuck you, Melrod. I’ll say what the fuck I want.”

The space between us shrank. I braced for incoming, but then Leyendecker [one of the recently elected young stewards] inserted himself between us. Leyendecker, at least according to him, had been a Navy SEAL. I admit, he threw down like a guy who knew how to fight.

“Go ahead, you redneck, bring it.”

The other old-school steward jumped in. “Let’s all cool it. Meeting’s over.”

“Yeah,” I said as Leyendecker and I turned to leave.

In a testament to the power of grassroots union democracy, the department meeting had taken up the key issue of racism, previously ignored or swept under the carpet.