Rave Up

Text by Shelley Lawrence

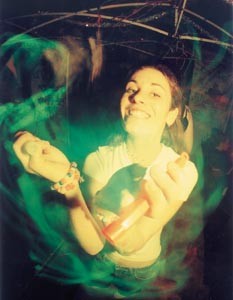

Photos by Brian Gaberman

NO, BABY, I don’t sell drugs!” Waldo says when asked for a comment on what it’s like being a drug dealer. “I just help my friends out. So, Shellacious, are you documenting everything, like, even the pre-rave trip to Safeway for power snacks?”

Waldo–a friend of mine whom I’ve chosen to follow around all night at the Harmony rave party–opens a plastic bag to reveal an air-sealed packet of Beer Nuts, an apple-cinnamon-oat PowerBar, a bottle of ginseng pills, three BlowPops, and a package of gum.

Gregarious and highly sought after, not for his snacks but for his illegal wares, the ever-grinning Waldo wears a red-and-white striped ski hat (as in the “Where’s Waldo?” kids’ book series), a bright-red polyester shirt peppered with large white polka-dots, a lime-green soccer jersey, and huge, tubelike jeans. His shoes remain a mystery because the elephantine pants cover his feet completely. He’s bedecked with sweet-colored plastic jewelry on all limbs, and peers at me through pink sunglasses that cover fully half his face.

Tonight, we’re on our way to a rave–a clandestine dance party characterized by ear-splitting electronic music at a location kept secret until hours before the event is announced on a voice-mail message. A blurb, printed on the back of the shiny, pocket-sized flyer that sports a picture of a baby swimming in a computer-generated star, lures ravers with visions of ecstatic experiences. The flyer reads like an advertisement for a New Agey self-help forum, promoting the event and setting the tone for the all-night happening: “On Saturday, Oct. 24, the Harmony Family will collectively go on a journey. A journey deep into our inner selves. We will connect not only with ourselves, but with our family as a whole. We will find the positivity and love inside that drives us all, and share it with our sisters and brothers. By dancing to celebrate life, love, and harmony, we will center ourselves and return to our INNERCENSE.”

It’s another episode in the scene that–with its big pants, funky dancing, electronic music, oddly shaped tennis shoes, and sparkly barrettes–first entered Sonoma County in 1992. Raves originated in London and northern Germany as huge (sometimes over 100,000 people), all-night, underground warehouse parties with live techno DJs galore, and spread from there into most of northwestern Europe, making the transition to America’s East and West coasts in the late ’80s.

These days, ravers are being chased out of the Bay Area urban centers where they were spawned. Greg Sandler, rave promoter and founder of the Santa Rosa-based Harmony party production company, claims that, owing to the intervention of San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, all Bay Area cities (excepting Oakland) have stopped issuing permits for the parties and shut their doors to DJs and drugs. Raves now are often held in out-of-the-way sites in the ‘burbs, but even there they are not free from hassle. Sandler claims that a recent Harmony party, held on private land in Vacaville, was broken up by Vacaville police. A lawsuit against the police department is planned, Sandler contending that the officers acted abusively and without provocation. Sandler refused comment on the lawsuit.

“Our job is to make these people trip out, and have an awesome experience. [A rave is] people all striving for the same thing. We all want to be loved and to have a community … . [For] a lot of kids we are there as their family–if they need help, we’re there; if they need love, we’re there; if they just wanna dance, we’re there,” says Sandler.

After a set, teenagers in bright yellow vests boredly usher us into a parking spot with green glow sticks. We enter Santa Rosa Armory’s rhythmically thudding hallway, which is hung with flowery, blacklit-glowing banners reading “We Are the Givers of Life.” We are patted down by same-sex bouncers and move into the main room.

Waldo’s glasses immediately fog over with the condensed sweat that hangs in the moist air.

“Groovy, baby!” he shouts in a nearly perfect Austin Powers impersonation, before bouncing toward the dance floor. “Sensory overload! Sensory overload!” screams my neocortex.

Once inside, I take stock of my surroundings. The decoration crew has done an impressive job with the armory’s austere interior. Suspended above a sea of wildly undulating, sweaty, glow-in-the-dark dancers, an enormous TV screen flashes computer-generated stars swooping over various landscapes. The ceiling is covered with drooping white veils, and on it brightly colored lights are projected from the corners and walls, casting quickly swirling threads of mesmerizing fluorescent green light. Large pink and blue stars appear occasionally around three huge disco balls.

The music isn’t at all the headache trance I’d expected. It’s intricate and, well, musical, and it’s hard to keep my feet still. The DJ, surrounded by scads of expensive equipment on the raised stage, intently mixes and spins loud techno-beat records. He’s doing a good job of matching the different bass beats perfectly and keeping the crowd’s mood high. I shuffle and bounce a little as I try to keep up with Waldo, who stops and chats with every second or third person we pass.

One of the main fashion themes is aliens: People are swinging plush alien backpacks, stuffed aliens are tied to the kids’ belts, and alien jewelry and clothing abound. The bathroom is filled with a swarm of girls (I’d guess their average age at about 14), wearing lots of makeup and practicing dance moves in the mirror–glitter covering their skin, pants hanging low, bright-colored shirts cropped right below their breasts, hair in kiddie pigtails.

As I wait in line, I’m given the once-over by several girls who appear to dismiss me, probably because of my now bland-looking street clothes: jeans, sneakers, and a tank top (maybe I would’ve been thought cooler if they’d seen my pierced tongue). But I feel less invisible when someone kindly hands me toilet paper over the stall as they hear my exclamations of dismay upon discovering the lack of supplies.

As I’m exiting, a young man wanders through the girls’ line. “Hey, Happy, what are you doing here?!” a beglittered and multicolored girlie shrieks. Happy grins vacantly and affirms that he always goes into girls’ bathrooms because the conversations there are much better.

I emerge from the restroom to find Waldo sitting on the floor, surrounded by a group of seven or eight girls (older than their counterparts in the bathroom, they look about 16), busily pasting him over with stickers. One reads “Hello, my name is Sasparilla Sweetcheeks.” He obligingly poses for a few photographs, kneeling among the girls, who look adoringly up at him.

It’s odd to see kids I went to high school with at this rave. A girl I knew is wandering around in running pants and a leopard-skin bra, sucking on a baby pacifier (to keep her teeth from breaking when her jaw starts to clench and chatter–symptoms that appear about two hours after taking the popular hallucinatory drug Ecstasy). She keeps tripping over her feet.

Many kids are wearing paper surgical masks that I find out have been soaked in Vicks VapoRub or eucalyptus oil, which is supposed to enhance any kind of high.

I consider borrowing a pacifier to keep my teeth from being jolted out of my head by the shaking bass that permeates every corner, even outside.

Waldo ambles over to a group of guys and begins removing his stickers and talking about what he did last weekend. The conversation revolves around drugs and parties past, the logistics of warehouse renting, and the designing of glossy fliers.

“Listen, you can take it or not,” he says to a dubious-looking young man. “You can have it, man. Put it in a bowl and smoke it–do whatever you need.”

Waldo hands the pill over and accepts in return a free capsule of “prescription speed,” whose donor recalls, “Uh, I can’t remember what it’s called, but it will get you a helluva high. My ex-girlfriend used to take it.” Waldo swallows it cheerfully with a gulp of water from his industrial-sized bottle. He sells two hits of Ecstasy (at $20 each, the standard price) from a full sandwich bag and then pulls out another baggie.

“This is St. John’s wort, baby! It’s a mood enhancer. Just try it and see.”

He turns quickly to a few people who have congregated on his other side. “You want some pills? The best, baby, the very best. I have zee best pills.” He sells another three hits of “E,” “pills,” or “candy,” depending on whom you ask. Waldo’s giving away free ginseng and St. John’s wort. My theory is that when he gives potential buyers free “drugs,” it makes him more popular, thus making it easier to sell more of the real McCoy. I notice that the eyes of the people who are milling about with pacifiers in their mouths are growing notably wider. One teenaged girl, overhearing Waldo’s conversation, gazes at him and then says emphatically, “Life is not reality. Reality is not life.” She takes a drag of her cigarette.

“What do you mean by that, baby?” asks Waldo.

She thinks hard, takes a few more ecstatic drags, and says, “You know? Reality isn’t life! And life isn’t reality! Think about it, man, just think.”

A friend nods sagely, and they wander off together amid the muttered cries of “Doses, speed, crystal meth. Crystal, doses, speed.”

A wiry, bleached-blonde boy runs by, shouting loudly, “Does anybody know where I can get some crank?”

I wonder, do all these mind-altering substances create an illusion of community that isn’t really there? When asked about the use of drugs at his parties and the “friendship bonds” that they form, Sandler answers, “Is it an illusion or is it a reality? If you have that experience, then it’s reality. If kids come to do drugs, to experiment with their consciousness, then they need to experiment. Through raving, I learned how to be a good person here on earth, and I try to spread the word. Our main force is to give the kids a safe place to be with their friends.”

But others disagree with that assessment. A friend of mine named Jennifer, who used to rave but has since become disillusioned with the scene, sums it up this way: “It’s too synthetic. Synthetic lights, synthetic music, synthetic drugs, synthetic feelings … I just can’t be around it for too long anymore. Plus, it’s scary to see all those 15-year-olds running around with pacifiers in their mouths, all high on drugs.”

My own night of rave ends early. After two hours, this “safe place” is starting to drain me. I’ve been asked three times if I want to buy drugs, twice if I have any to spare. I’m sweaty; my head hurts from speedy music, gyrating lights, and too many spinning dancers with glow-sticks. I walk quietly home, thankful to be inhaling deep breaths of smoke-free air.

From the December 31, 1998-January 6, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.