Class War

Always Running doesn’t belong in classrooms.

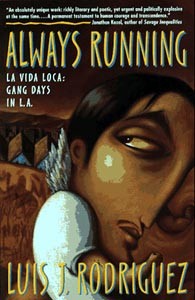

Luis Rodriguez casts a skeptical eye on attempts to ban his autobiography

By Patrick Sullivan

IT’S A HARD-CORE book. I’m the first to admit that,” says Luis Rodriguez. “There’s a lot of graphic material. But that’s done for a reason. There’s no way you can write this kind of book without getting as close as possible to what these young people are going through.”

Speaking by phone from his home in Chicago, the controversial author maintains a remarkably even tone as he discusses ongoing efforts to boot his award-winning autobiography out of school libraries and classrooms across California. His gravelly, lightly accented voice betrays no hint of anger as he tallies up the growing list of bitter battles over Always Running–a graphic account of life among L.A. street gangs. Last July, the Santa Rosa Board of Education voted unanimously to sharply restrict use in district schools of the 1993 book. Recently the book has been the focus of school board struggles in Fremont and San Jose, and just last week San Diego began to grapple with the issue.

Rodriguez is fighting back by speaking out in defense of his life’s story. He will appear at the Sebastopol Veterans Auditorium on Feb. 20 to talk about Always Running at a banquet given by the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, which recently sponsored a high school essay contest on the issue (For the winning contest entry, see “Contest Winner, next page). And no matter how nasty the fight gets, here or elsewhere, the author says he’s determined not to take the attacks on his book personally. He has, after all, been through all this before.

“In Rockford, Illinois, when they banned my book, which was the first time [book banning] was ever done in the Rockford school district, they went ahead and banned 16 other books,” he says. “So there seems to be more than just my book at stake. There’s an agenda of keeping other voices, certain experiences, certain kinds of literature out of the hands of our kids. It’s bigger than just Always Running.”

About the only time Rodriguez does get hot under the collar is when he starts discussing common attitudes toward the troubled kids his book was intended to help, the at-risk teenagers that he still works with as a youth counselor and community organizer. Many people, Rodriguez says, don’t understand inner-city kids and gangs half as well as they imagine they do.

“They don’t know these kids,” he says emphatically. “They haven’t spent time with them. People want to be tough on crime, but I tell you, the toughest thing is to walk down these streets, to care about these kids. That’s tough.”

Banned in Santa Rosa?

A Windsor High School student speaks out on the controversy.

Life on the street is a subject that the author himself, now 45, understands from firsthand youthful experience. Born in Mexico, Rodriguez grew up in East Los Angeles amid poverty, racism, and gang warfare. By the time he was a teenager, he’d witnessed countless acts of savage violence committed by everyone from gang members to the L.A. Sheriff’s Department. As he explains in Always Running, Rodriguez joined a local gang because it seemed to offer protection and power in a dangerous world: “I was a broken boy, shy and fearful. I wanted what Thee Mystics had; I wanted the power to hurt somebody.”

But years spent immersed in La Vida Loca, the crazy life, left a terrible mark on the young man. Suicide, murder, and drugs took the lives of friends and family members. Slowly, painfully, he broke free from violence and despair, and eventually went on to become an award-winning poet (his latest book is Trochemoche), an activist, and a journalist.

Then, in the early ’90s, Rodriguez saw his 15-year-old son, Ramiro, descending rapidly into gang life. Determined to educate and protect the boy, the author put his own youthful experiences down on paper. Always Running was the provocative result.

Critics of the book argue that, far from preventing gang violence, Always Running actually glorifies it: “Mr. Rodriguez is long on graphic sex, drug abuse, and violence, but short on consequences,” one speaker told the Santa Rosa Board of Education.

Rodriguez is flabbergasted by such views.

“I would say they haven’t read the book,” he says. “It does not glorify or demonize gang involvement. Both views distort reality. I work with gang kids today, and I realize that these kids have rational reasons for joining gangs, and I also realize that it can be very destructive and against their own dignity and value as human beings. It’s a complicated thing, and we should spend time looking at it.”

What, exactly, is all the fuss about? Here’s one excerpt from Always Running that’s outraged critics: “The dude looked at me through glazed eyes, horrified at my presence, at what I held in my hands, at this twisted, swollen face that came at him through the dark. Do it! were the last words I recalled before I plunged the screwdriver into flesh and bone, and the sky screamed.”

Could Rodriguez have told his story without the use of graphic language? Would the book have packed the same powerful punch?

“I’m convinced it wouldn’t,” the author says. “There’s a level of authenticity, a level of ‘Do you know what you’re talking about?’ You can’t just preach to people about this. What the kids are living is even worse [than what I wrote]. The sex scenes are nothing compared to what some of these kids are going through today. The drug scenes, which are very vivid in my book, are so much worse now. The violence, even as terrible as it may have been in my book, is just more extensive and more intensive today. “

Some observers, including the ACLU, argue that racial tensions play an important role in the Always Running controversy. All the critics of the book who addressed the Santa Rosa Board of Education in July were white. Among the book’s most ardent defenders were several Latino youths. That’s no surprise to Rodriguez, who says he’s seen this pattern repeated in other communities across the nation. He chalks the division up to what he calls the country’s “highly polarized” racial climate. But for those white critics who go so far as to argue that a book about gangs has no possible relevance for children in their affluent suburban communities, the author offers a wake-up call.

“The fastest rise of gang membership in this country is among suburban white kids,” Rodriguez says. “Parents don’t realize how much some of this stuff is actually going on. The drugs, the meth, the heroin, some of the crack, it’s going on in these suburban communities. It’s a kind of denial, that they’re above all of this.”

Despite his hopes, Always Running did not achieve everything that Rodriguez had hoped for. The book helped for a time, but last year his son Ramiro was sentenced to prison for attempted murder. That fact was seized upon by activists in San Jose in an attempt to discredit Rodriguez, a tactic the author calls “ugly.”

“They said, ‘If he couldn’t help his own son, how can he help others?’ ” Rodriguez recalls. “But that’s just not the way it works in the real world. I’ve mentored a lot of kids out of the violence, kept them in school. The fact that my son is in prison doesn’t make him the worst person in the world either. He’s still a poet, he’s still a leader. He did leave the gang, by the way. He made a terrible mistake, and he will pay the consequences. But I don’t think he should be written off.”

As for the struggle over the book itself, Rodriguez expresses hope that eventually, through open and honest discussion, communities and school boards will come to terms with the controversial subject. He’s looking forward to a time when it’s no longer an issue.

“I actually hope that my book will lose its validity some day, that there isn’t a need for a book like Always Running,” Rodriguez says. “That we don’t have gangs, and kids killing each other, and drugs in the communities. I hope that some day it becomes obsolete. But right now that’s not the case. The book is very relevant, and as long that’s the case, then we should make sure that people can get access to it.”

From the February 4-10, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.