Cycling is a great way to stay physically active. Biking is a carbon-free means of commuting and getting out of soul-sucking traffic. Slowing down and riding a bike lets you see things you would otherwise miss locked inside a speeding car. But the best reason to ride a bike is that it’s fun. And we need more fun.

The North Bay’s scenic coastal and vineyard roads and rocky trails through redwood and oak forests make the area a cycling mecca. As summer shifts into high gear, we celebrate two-wheeled pleasures with our first annual cycling issue and survey of the North’s Bay’s cycling scene. Also, on page 14, see where to get an espresso and bike tune-up, and find our story about the new Marin Museum of Bicycling and Mountain Bike Hall of Fame in Fairfax on page 21. Have a look, and then go for a ride.—Stett Holbrook

FITZ CYCLEZ

The garage is fertile ground for creative minds, be they musicians, engineers or artists. John Fitzgerald’s garage is no exception. In the back of his

St. Rose neighborhood home in Santa Rosa, amid the washer and dryer and tidy storage boxes, Fitzgerald builds beautiful steel bicycle frames for a devoted clientele under the Fitz Cyclez (fitzcyclez.com) brand.

The dirt trails and winding roads of the North Bay have long been a draw for cyclists and frame builders. The list of North Bay bike builders is long and storied: Joe Breeze (Breezer), Scot Nicol (Ibis), Ross Shafer (Salsa), Josh Ray (Soulcraft). Great riding attracts great frame builders.

But it was affordable housing, not cycling, that drew Fitzgerald and his family to relocate to Santa Rosa from San Francisco one year ago. The cycling scene was a bonus.

“The roads here are perfect for it,” says Fitzgerald, who has been building bikes for 10 years.

Fitzgerald, 43, a lanky man with glasses and a long goatee, began working on bikes during his time with AmeriCorps in Austin, Texas, as part of the Yellow Bike Project, a nonprofit bicycle-advocacy group. He went on to apprentice in frame building for Rock Lobster in Santa Cruz and Banjo Cycles in Madison, Wis., before setting out on his own almost four years ago.

Fitzgerald specializes in road and randonneur bikes. Randonneur bikes are built for all-weather, day-and-night, long distance rides. As such, the bikes have fenders, light systems and smalls racks for holding food and gear during self-supported rides.

“It’s a niche market that the big guys aren’t tapping into,” Fitzgerald says.

Randonneuring began in France as an alternative to competitive cycling. Randonneuring is not about racing, but getting from A to B and enjoying the ride and the company of fellow cyclists along the way. In events called brevets, riders must complete a course with stops at checkpoints along the way in set times, no earlier and no later.

While carbon fiber and full suspension bikes are all the rage, steel is Fitzgerald’s material of choice. It’s the material he knows best, and it appeals to his old-school aesthetic. He’s drawn to the lines and details of French-made bikes from the 1950s and ’60s, and he works in some of the style and design elements from that era into his frames.

“I’ve always had an affinity for older things,” he says.

He built himself a sharp-looking, single-speed mountain bike with a retro rigid fork, and delights in keeping up with riders on bikes tricked out with full suspension and other modern components.

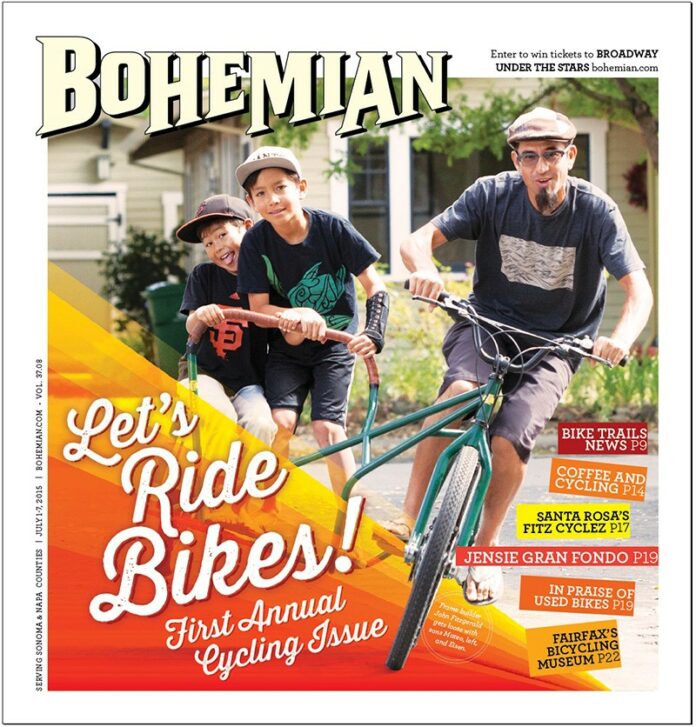

Fitzgerald’s wife, Sandra, is a psychology professor at San Francisco State University. He’s a stay-at-home dad who builds bikes in between school drop-offs, pick-ups and baseball practice. For his sons Mateo, seven, and Eisen, 10, he built a “side-hack,” basically a bike with a sidecar. He gets plenty of smiles when the three of them roll around town.

Custom bikes can cost as much or less than a store-bought bike. If you’re particularly tall or short, having a bike built to your measurements makes for a much more comfortable ride. And if you want something you don’t see on the market, like a rando bike, a custom build can be the way to go. His frame and fork sets start at $1,275.

“You want something funky that’s within reason,” says Fitzgerald. “I’ll build it.”—Stett Holbrook

JENSIE GRAN FONDO OF MARIN

Jens Voigt may have retired from pro cycling, but he’s still riding hard on the heels behind Levi Leipheimer. This year, the German cyclist lends his nickname to the inaugural Jensie Gran Fondo of Marin on Oct. 10 (thejensiegranfondo.com), trailing Sonoma County’s popular Levi’s Gran Fondo by just one week.

“It’s going to be a great event,” says Jim Elias, executive director of the Marin County Bicycle Coalition (MCBC). “It brings in one of the most iconic cycling personalities of our era.”

Voigt, a resident of Germany who announced his retirement in 2014, loves to ride in Marin, according to Elias. “He’s also quite a personality and a lot of fun,” Elias adds.

[page]

Voigt will ride the entire route with participants, and not just at the head of the pack.

“He’s not here to race; he’s here to be an ambassador, to share his wisdom and experience with all the riders,” says Scott Penzarella, a cofounder of the event and owner of Studio Velo in Mill Valley.

A portion of the funds raised by entry fees will benefit the MCBC for its bicycle education and advocacy programs, such as Safe Routes to Schools.

Part of the appeal for cycling fans is the opportunity to ride with the famously gregarious Voigt, who’s been called “the most fun guy in pro cycling.” Also known for his “attack” style of riding, Voigt placed second after Leipheimer in the 2007 Amgen Tour of California and triumphed in several stages of the Tour de France. Retiring in his “young 40s,” he stuck with it longer than most, says Elias.

Entry fees for the Jensie Gran Fondo, priced from $95 to $749, correspond to routes of increasing length, elevation, service and swag.

The 100-mile “Shut Up Legs” route ($195) gets its name from a signature Jensism, and takes riders up to Alpine Dam and around Mount Tamalpais.

The first such event for Marin County, the Jensie Gran Fondo kicks off at Stafford Lake Park in Novato and threads through the hills of West Marin. It’s not a race and it’s not only for hardcore competitors, although riders who finish before 5pm will be timed by electronic chip.

“Some people ride ambitiously,” Elias says, “but for most people, it’s a big cycling celebration.”

While CHP will offer support at major intersections, the mainly rural ride will not close down roads, and participants are encouraged to ride single file.

All routes lead to a gourmet service stop in Point Reyes Station with local food purveyors, and end at Stafford Lake Park for a festival with music and, of course, a local microbrew to shut up that thirst.—James Knight

USED BIKES, FRESH FUN

Bikes are expensive. Some can cost as much as a used car. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Everyone can own a bicycle. Used bike shops sell bicycles than can range from 50 days old to five decades old and cost a couple hundred dollars instead of a few thousand. The shops also offer repair services to restore old bikes, and some will teach you how to fix them yourself.

Santa Rosa’s Bicycle Czar

(201 Santa Rosa Ave., 707.528.8676) opened in 2007 and is the original used bike shop in Sonoma County, says owner Brooks Van Holt. His mission, he says, is “to bring order to the used bicycle world.” His business offers services and vintage parts rarely found anywhere else. The business is a resource for used parts and information on bikes of days

gone by.

“It’s fun not knowing what is going to come through the door,” says Van Holt. “That’s the exciting part. It could be something that was bought this year or last year, or something that has been hanging in a garage for 50 years that needs to be refurbished. We’ve got our technique down, and we know how to bring bikes back to life.”

Bird House Bicycles (birdhousecycles.com) owner Drew Merritt started his repair business after finding a used bike himself and discovering the market for them. His business is run on his parent’s west Sonoma County property in a red barn.

He crams in as many bikes as he can and gets them roadworthy.

He also offers classes on bike repair.

“I try to think of the average working man or woman who doesn’t need an $8,000 bike, who just needs a point-A-to-B bike,” says Merritt.

Frank Hinds, owner of Uncle’s Crusty’s Bike Shop (2076 Armory Drive, Santa Rosa; 707.292.4644), was originally a buyer or “picker” for Bicycle Czar and started his business after learning the trade. He’s interested in promoting cycling and helping customers who don’t want to spend $4,000 to get started.

“We provide a cost of bike and a cost of service that’s lower than other bike shops in town, so we have a different client base,” Hinds says.

All these businesses focus on recycling and returning bikes to the community, and each shop has bicycle gems awaiting discovery—and a ride.—Haley Bollinger.