Language on the Line

Poetry as the ultimate act of self-creation

By Louise Brooks

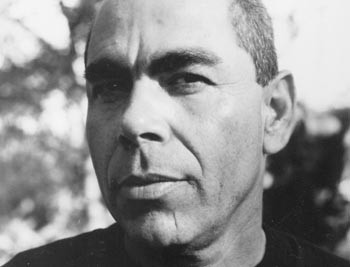

IT’S CLEAR from Jimmy Santiago Baca’s voice that he hasn’t done an interview in a while. Talking on the phone from his home-office in Albuquerque, N.M., the poet seems happy to talk, is constantly laughing along with his comments, and expects an interviewer not only to ask questions, but to answer them as well.

Baca–who will be in town July 14 for a reading at the Sonoma Valley Poetry Festival–has been sticking close to home in recent years, passing up teaching opportunities in order to “live among the coyotes and the horny toads, and track down a roadrunner to see where its nest is.

“That gives me pleasure,” he explains. “I can write about that. So that’s what I do. I try to not distract myself with Madonna’s newest CD.”

Over the past two decades Baca has gained recognition, numerous literary awards–including the American Book Award–and chairs at Yale and Berkeley for his lyrical volumes of poetry (Immigrants in Our Own Land, Martín & Meditations on the South Valley, Black Mesa Poems). His vision focuses on the arid, impoverished, searingly beautiful Southwestern landscape of his youth.

Much of his poetry and autobiographical writing (Working in the Dark: Reflections of a Poet of the Barrio) also focuses on his continual rebirth through poetry. He does not describe an easy, blissful emergence, however. His is a wrenching, painful birth from which the poet emerges, ragged, bloody, and squinting in the light.

“It really is beautiful to encounter pain,” Baca says, “because right behind the pain is God waiting, you know? . . . But we gear this whole society, everything we have, and everything we do, to go away from pain.”

Pain has not been rare in Baca’s own life, as he makes clear in his long-awaited memoir, A Place to Stand: The Making of a Poet, out this month from Grove Press, which is also publishing a new collection of his poems, titled Healing Earthquakes.

Baca grew up in New Mexico, largely by himself, spending some time in an orphanage. He points out, however, that his self-sufficient childhood gave him a huge freedom of imagination and exploration. “Left to the resources of a child’s innocence,” he says, “I think it’s really amazing what can happen.”

But his life took an ugly turn. Hitting the streets as a teenager with few resources and no education, Baca soon ended up in prison on drug charges. It was in prison that Baca stole a book of Romantic poetry and taught himself to read and write. It was a process he compares to putting on glasses for the first time and discovering he’d needed them his whole life. He remembers the first poem that he wrote during this time.

“I was naked in the shower,” he recalls. “I was in prison, and I think I was reading Turgenev. I soaped myself up, and all of a sudden I got hit with a lightning bolt. You know how they call it the ‘muse’? I call it the ‘Mohammed Ali left hook.’ These lines came to me, and I ran out of the shower naked, and the guard hit the alarm button, because you can’t run, you know?

“Besides, there goes a naked Mexican running down the hall, so what are you going to do?” Baca continues. “He hit the alarm button, and I ran into my cell with soapy hands and stuff, and wrote down these six lines of poetry. And then of course, the soap got in my eyes and reality came back and I had to rush back to the shower to wash the soap off. But at that point I think I was classified as a nutcase.”

The poem was a response to a group of senators who had come touring through the prison the previous day, examining the aftermath of a riot. Baca’s first poetic refrain was: “Did you tell them, that hell is not a dream, that you’ve been there, did you tell them?”

If prison was hell, then poetry was Baca’s salvation. In fact, as his new memoir makes clear, poetry literally saved him from becoming a murderer. As Baca tells it in A Place to Stand, he was standing over another convict with a weapon, ready to finish him off. Suddenly he heard “the voices of Neruda and Lorca . . . praising life as sacred and challenging me: How can you kill and still be a poet?”

These days, Baca is almost as well known for his work with at-risk youth as he is for his poetry. He’s given workshops to homeless teens, to prison inmates, and to kids in a juvenile detention center. Partly, Baca believes that poetry gives voice to individuals who might otherwise remain silent.

He writes about the silence that he witnesses in the Latino community, a silence he terms “protective.” He argues that when Latino kids grow up hearing that their community is filled with nothing but drugs and crime, and they know this not to be true, they learn to mistrust and remain silent around the society that tells them this.

Baca says his work with kids also keeps his own voice strong.

“There’s dead languages that you study in classical-language departments that are never used,” he says by way of explanation. “And then there’s the language that you hear on the street corner, or the language that you hear on Wall Street, or the language that you hear during the Beat generation, or the rappers, or techno people. You have all these different kinds of languages that are immediately describing the lived experience of people that are [living] now.

“I don’t dismiss the academic and scholarly sectors of society,” he continues. “I go listen to what they say, and I read what they write. But it’s not near as exciting as hearing language invented from experiences that have truly been lived, almost, in many cases, on the verge of dying.

“I’ve never heard a professor stand up and say, ‘I’ll give my life for this,’ ” Baca continues. “And yet I listen to these kids and they say, ‘I’ll give up my life, I put my life on the line with this poem about my mom.’ And I’m like, ‘Wow.’ That keeps educating me about where my poetry should be.”

ULTIMATELY, for Baca, poetry becomes a personal process of representation and creation. Through the act of writing, Baca constantly re-creates himself; he becomes a man capable of healing some wounds and humble enough to accept that others cannot be healed.

“You can’t write poetry and be an asshole,” Baca claims. “Not while you’re writing it. You can be an asshole after you write it. I’ve heard some really bad poems in my time, but I’ll bet you the person felt like a saint when he or she was writing it. So I’m saying that the act of writing poetry is a beautiful act.”

He starts to laugh. “It’s like seeing a dog pee on a fire hydrant. It’s just so natural, so normal, it’s just the way it goes.”

Jimmy Santiago Baca reads on Saturday, July 14, at 7:30 p.m. at Readers’ Books, 130 E. Napa St., Sonoma. The Sonoma Valley Poetry Festival continues through July 29 at various venues. For details, call 707/280-4696.

From the July 5-11, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.