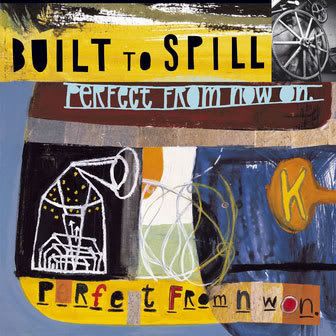

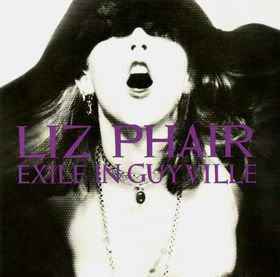

The news hit like a one-two kiss of sloppy, wonderful indie-rock love: both Built to Spill and Liz Phair have announced that they’ll perform their great masterpieces—Perfect From Now On and Exile In Guyville—in a series of shows around the country this year.

The news hit like a one-two kiss of sloppy, wonderful indie-rock love: both Built to Spill and Liz Phair have announced that they’ll perform their great masterpieces—Perfect From Now On and Exile In Guyville—in a series of shows around the country this year.

I’ve fielded countless questions about if I’m going to these shows, because of a truly million-to-one coincidence: I myself have actually performed both of these albums.

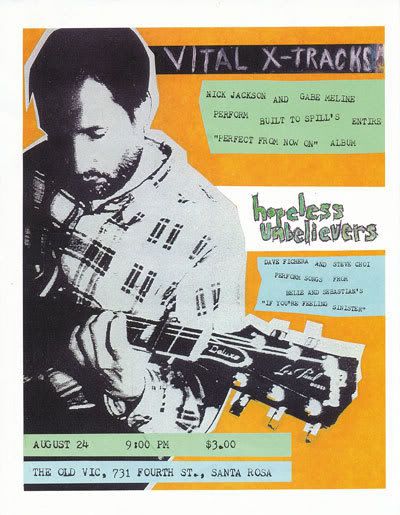

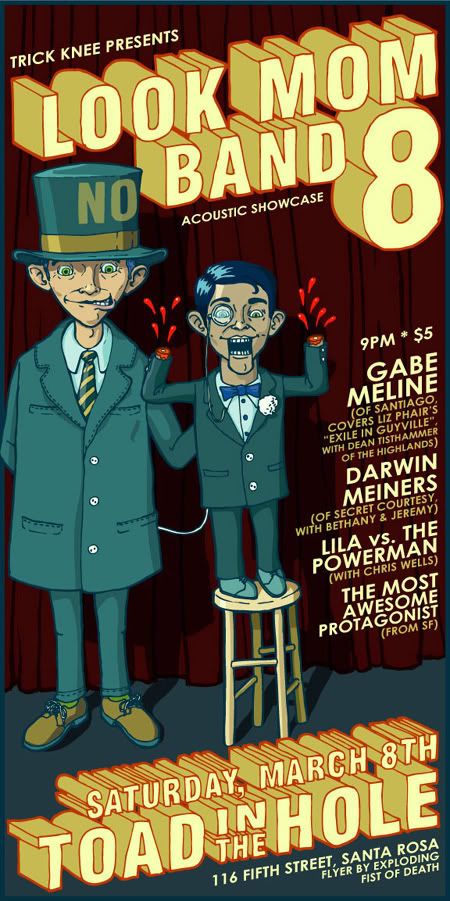

Okay, so maybe it’s not a million-to-one shot, but it’s pretty uncanny: in 2001 as part of a duo, and then again in 2006 with my band, Santiago, I learned and performed Perfect From Now On in its entirety. Earlier this year with my friends Dean and Steve, I learned and performed Exile In Guyville. And now, as if to answer our weird but urgent prayers, both albums are getting the ‘In Its Entirety’ treatment by the OGs.

I’m not claiming any kind of cosmic credit for altering the creative waves of the universe. Lets face it, Sonoma County’s not that big. But I will gladly use the news as a reason to talk about what it was like to learn two of the best records of the 1990s.

As anyone familiar with Perfect From Now On and Exile In Guyville can imagine, they were incredibly daunting projects to take on, especially since I had to not only figure out some truly otherworldly guitar parts but also remember hundreds of lyrics. Yet each album compelled me. They’re both crammed with mystery. I felt like if I could wrestle with them in the most direct way possible—figuring out how to play them, and then playing them in public—I could unlock some of that mystery.

As anyone familiar with Perfect From Now On and Exile In Guyville can imagine, they were incredibly daunting projects to take on, especially since I had to not only figure out some truly otherworldly guitar parts but also remember hundreds of lyrics. Yet each album compelled me. They’re both crammed with mystery. I felt like if I could wrestle with them in the most direct way possible—figuring out how to play them, and then playing them in public—I could unlock some of that mystery.

When I first heard Perfect From Now On I hated it. All the songs were long and slow and repetitive, and it didn’t grab me at all. Then Built to Spill put out Keep It Like A Secret, which I instantly loved. “Finally,” I said, “I understand what all my friends have been crazy about!” So I went back and listened to Perfect From Now On. I still thought it was a boring formless piece of shit.

It was, however, a boring formless piece of shit that I kept coming back to, and I can’t explain how it happened, except that one night I was sitting alone in my apartment half-drunk, pitifully alone and staring at the carpet, and “Velvet Waltz” came on, and Doug Martsch sang those lines:

And you’d better not be angry

And you’d better not be sad

You’d better just enjoy the luxury of sympathy

If that’s a luxury you have

Suddenly, Perfect From Now On was the most incredible revelation in my entire life, bursting from its ruminations on the meaning of eternity to its sharp, final accusation: what are you gonna do? As a salve for one of my darkest hours, I listened to it every day and every night for a week, over and over. It was an enormous ocean, and I swam through it like a lost soul from a shipwreck, looking for an island.

I’d heard about a guy named Nick Jackson who played guitar and who knew how to play some Built to Spill songs, so I called him completely out of the blue. “Hi, Nick? Hey, my name’s Gabe. Rob gave me your number, and he says you know some Built to Spill songs on the guitar. I’ve got a totally ridiculous idea for you, and feel free to say no, but do you want to learn Perfect From Now On with me and play it at a show?”

His classic response: “Uh, sure. What’s Perfect From Now On?”

He went out and bought it and quickly and amazingly learned every single note, and we started practicing two weeks later. Just us and our guitars, with me singing. The show, at the Old Vic, went well, and afterwards I felt like I’d not only conquered the record in a way, but also made personal amends for talking so much shit about it all those years.

He went out and bought it and quickly and amazingly learned every single note, and we started practicing two weeks later. Just us and our guitars, with me singing. The show, at the Old Vic, went well, and afterwards I felt like I’d not only conquered the record in a way, but also made personal amends for talking so much shit about it all those years.

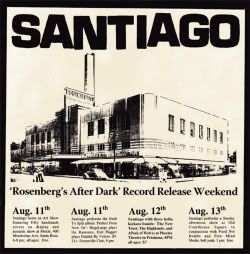

Fast-forward to 2006, and Santiago’s just finished recording Rosenberg’s After Dark, a sprawling concept album all about Santa Rosa. We needed to clean out our systems, so we started fucking around with There’s Nothing Wrong With Love. But it didn’t seem right, and we kept coming back to the songs from Perfect From Now On. It sure sounded a lot better with a full band. I called up Nick Jackson, who was down to fill in again on guitar, and we planned the ultimate joke: for our record release show, we’d play someone else’s record.

It was such an excellent idea. Then my world fell apart. In the middle of rehearsing, my mom died in a terrible car accident. Suddenly Perfect From Now On took on an entirely new emotion for me, and all of its intertwining mystery came rushing back. There was a lot of pain and confusion and heartache going on, and just as the album had earlier given me a salve for my solitude, it sprang up again and offered me a cathartic way to say goodbye.

The show we played was a blur. I remember only one thing vividly about it: singing those lines from “Velvet Waltz”—the ones about about anger, sorrow, and the luxury of sympathy. Someone recorded the show, and when I hear myself singing those lines today, I realize that I’m not one step closer to understanding Perfect From Now On. It’s still a vast ocean, and for as long as I spent swimming around in it, I never found the island. I like it that way.

The show we played was a blur. I remember only one thing vividly about it: singing those lines from “Velvet Waltz”—the ones about about anger, sorrow, and the luxury of sympathy. Someone recorded the show, and when I hear myself singing those lines today, I realize that I’m not one step closer to understanding Perfect From Now On. It’s still a vast ocean, and for as long as I spent swimming around in it, I never found the island. I like it that way.

Exile In Guyville is another story altogether.

I have an ex-girlfriend who listened to Exile in Guyville all the time when we were together. I’d heard about the album when a friend of mine saw Liz Phair on the cover of Rolling Stone, and at first I thought it was basically a wimpy soft-rock record with some token sex references thrown in for attention’s sake. I couldn’t understand why my girlfriend loved it so much, but how can you argue with a girlfriend who loves songs about sex? So I put up with it. She played it over and over.

Eventually, in a haze of prescription Vicodin and Seagram’s gin and English ovals, Exile In Guyville sunk in. I realized that there’s a lot of songs on the record (like “Explain it to Me”) that drone in a really cool way and some (“Dance of the Seven Veils”) that are just plain surreal, lyrically. Those are the ones that I really fell in love with. The eerie ones. My girlfriend kept on playing the ones about blowjobs, though. Years later, as our relationship soured, she kept turning to the blowjob songs for support, and I decided that I couldn’t understand her anymore at all if she still, after all those years, found more solace in “Fuck and Run” than in “Shatter.” So fuck her and fuck Liz Phair and fuck that record, I thought.

Songs don’t disappear. I eventually bought Exile in Guyville again, cuing up my favorite songs first, of course, and then listening to the whole thing. A healthy dose of distance from the mitigating circumstances of its arrival into my life helped me appreciate it all over again. And again, I picked up the phone and called some people and somehow talked them into learning it and playing it in public.

Songs don’t disappear. I eventually bought Exile in Guyville again, cuing up my favorite songs first, of course, and then listening to the whole thing. A healthy dose of distance from the mitigating circumstances of its arrival into my life helped me appreciate it all over again. And again, I picked up the phone and called some people and somehow talked them into learning it and playing it in public.

This idea actually had its genesis in 1995, when I distinctly remember walking around a small town in Indiana, waiting for a flat tire to get fixed, singing “Fuck and Run” in my best Johnny Cash impersonation with Alyssa. How crazy would it be, I asked, to take on the ultimate indie-rock feminist statement and perform it from a male point of view?

13 years later, I had even more of a reason to learn and perform Exile in Guyville. Liz Phair had started completely embarrassing herself with teen-girl-whore pop bullshit, and I needed to remind myself and others that she was once great. Also, there was a serious element of reclamation involved; a personal creed, I suppose, that I could love a record on my own terms, and that it didn’t belong to any one person, or to one ex-girlfriend, or to one gender, or to one line of thinking. Plus, a couple years after being stranded in Indiana together, Alyssa had died of a heroin overdose, and I always remembered that she thought it was a cool idea.

We learned the thing in about 4 or 5 practices, cramped into my small office room, and it was an amazing musical experience. Lots of unnerving surprises. I played piano on “Canary.” The show went incredibly well—even the songs about blowjobs—and I think, somehow, we achieved our goals. If nothing else, it was intensely satisfying.

My favorite Exile in Guyville song is still “Shatter.”

So anyway, the long and short of all this is that no, I don’t think I’m going to see Built to Spill perform Perfect From Now On in its entirety, nor do I fathom I’ll go see Liz Phair perform Exile in Guyville in its entirety. The purpose of going those kinds of shows is to commune, in the most direct way, with an album that you love, and I feel like I’ve already done that in the best way possible. Actually, I feel like I’ve inhabited those albums—and to paraphrase the song, I’m not sure I want to go back to the old house.

TRENDING:

Awesome article. That Vital X-Tracks show was a life-changing experience. Thanks for recreating it so eloquently.

[…] triumphant Berkeley show last year, in which they performed their masterwork Daydream Nation in its entirety, the subject even crept into the heckles. Bassist/vocalist Kim Gordon responded by reminding how […]

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new feedback are added- checkbox and now each time a remark is added I get 4 emails with the identical comment. Is there any manner you’ll be able to remove me from that service? Thanks!