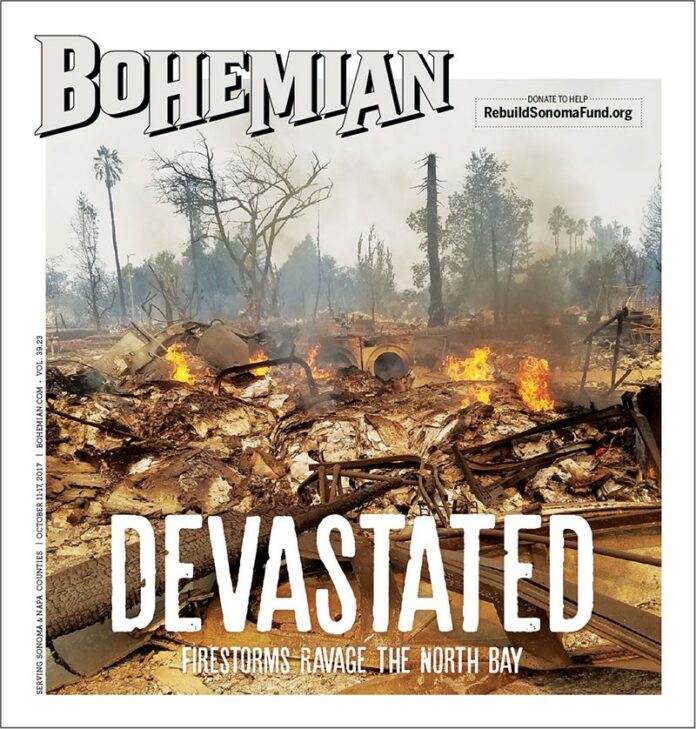

Devastating. Apocalyptic. Unprecedented.

Survivors of Monday’s North Bay firestorms used different words to describe the intensity of the wind-whipped, early-morning blazes that left much of the North Bay a smoking ruin, took at least 13 lives and left authorities looking for 150 missing people. By Tuesday, the multiple blazes in Sonoma, Napa and Mendocino counties were zero percent contained and more than 20,000 people had been forced to flee their homes after the worst natural disaster in Northern California history.

As of Tuesday afternoon, the fire was threatening the Oakmont Village retirement community and some 5,000 people were still in evacuation centers in Sonoma County—and nobody was being sent back home yet. PG&E reported that more than 100,000 people were still without power. Sonoma County Sheriff Rob Giordano said his department is “working on damage assessments so we can put people back in their homes” during an afternoon press conference where he stressed safety and patience. By Tuesday the death toll across the region had risen to 15, nine in Sonoma County, and more than 50,000 acres were burned in the Tubbs and Atlas fires in the Santa Rosa area and Napa County, respectively.

Santa Rosa police and the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office (SCSO) were on guard against looters, and the city enacted a dusk-to-dawn curfew; the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office closed access to mandatory evacuation areas and Giordano reported that increased police presence had contributed to “very few calls and no looting.” Fourth Street downtown was a shuttered ghost town as of Monday afternoon, except for the Chinese restaurant which was serving through the smoky day. It started to come to life again Tuesday, but school was out, the courts were closed and the SMART train was limiting its service. Twenty employees of the SCSO lost their home to the fire, says Giordano. One employee of the Bohemian lost hers.

“This is a huge event. This is an enormous fire,” Giordano told reporters. He added that he expected that there “may be a couple more” fatalities in the county.

The estimated number of homes, businesses or other buildings destroyed by the multiple fires was at least 2,000. The Tubbs fire, says Cal Fire spokeswoman Heather Williams, has claimed 571 buildings, 550 residential and 21 commercial. “There are 16,000-plus structures that are [still] being threatened,” she says. That fire started along the Sonoma-Napa County border Sunday night in Calistoga. Its cause is under investigation, Williams says.

The damage is numbing in its scope and cruelly democratic in its reach: rich and poor alike have lost everything to Tubbs. Local institutions are no longer: Santa Rosa’s Hilton Sonoma Wine Country Hotel and historic Round Barn in Fountaingrove. Gone. The eastern side of the Luther Burbank Center for the Performing Arts. A charred ruin. Kaiser and Sutter hospitals evacuated before the approaching flames. Paradise Ridge Winery. Reduced to ash. Downtown Glen Ellen, gutted. Arby’s. Trader Joe’s. K-Mart. Gone, gone and gone. McDonald’s, too.

Santa Rosa’s Coffey Lane neighborhood north of Piner Road, lit by embers that jumped Highway 101, was the site of utter devastation. Block after block of middle-class homes surrounding Coffey Park were reduced to smoldering ash. Bohemian contributor Thomas Broderick reports that he evacuated with his uncle early Monday morning and faces financial stress along with the loss of his home. He is not alone.

Long after firefighters and Sonoma County sheriff deputies worked through the early morning hours to save as many lives as possible, the working-class neighborhood once adorned with Halloween decorations had come to resemble a burned-out city under military siege.

The National Guard has been called in to assist SCSO, says Giordano. The Guard was activated after Gov. Jerry Brown’s state of emergency declaration yesterday; Giordano noted that they have search-and-rescue dogs and other assets. The county has fielded 240 missing persons reports, he said, and has “located 57 people safely.” He encouraged families to contact the county Emergency Operations Center if they have a missing loved one, and attributed much of the concern to the chaos of the moment, with panicked persons leaving their homes and heading to one of 25 evacuation centers—often without a cell phone or a cell charger. “A lot of it is just confusion,” he said. “I’m glad we can chip away at that number.”

All over the region, gas mains roared with perilous open flames and broken water pipes feebly spewed water onto scorched earth as the acrid smoke of incinerated beds, couches, cars, bicycles and lives drifted through the air. Residents shuffled back to the now-unrecognizable Coffey Park neighborhood to survey their losses. They stood before chimneys that looked like gravestones in a smoldering cemetery, weeping and taking photos with cell phones.

Seaneen DeLong, 57, walked south on Coffey Lane away from the fire with her yowling cat Fritz in a travel carrier.

“It was the best neighborhood in the world,” she says. “Now it’s a charred ruin. It looks like a nuclear wasteland.”

She was awakened by the fierce winds that sent embers from the Tubbs fire to the east into her neighborhood and was able to get out with her cat and little else.

Scott Murray, 60, was heading in the other direction, slowly walking back to check on several properties, a rental unit he owned on Dogwood Lane, his ex-wife’s house around the corner and his home on Vermillion Way. The rental house, the place where he raised his children, burned to the ground. So did everything around it. The absence of familiar visual reference points—and the shock of the devastation—left him disoriented.

“It looks like Dresden.”

His wife’s house was also gone and he called to give her the news. Then he trudged across Coffey Park, where it appeared a car had exploded and landed upside down, to check on his home. He expected the worst but suddenly the scene of destruction stopped. Like stepping from black-and-white into color, the destruction stopped. His home, just a few houses away from piles of ash and twisted metal, was untouched.

“Oh my God,” he said, overcome with emotion. “Oh my God. How was my house spared?”

Chris Highland, 68, didn’t know what became of his residential-care facility in Fountaingrove, one of the hardest hit areas of the fire. He was evacuated early Monday morning. He milled around Santa Rosa Fire Station No. 3 near the Coffey Lane catastrophe.

“There was fire all around the place. It was unbelievable. It was just solid fire.”

On Monday morning, the scene was eerily calm, yet blazingly dangerous at the curving corner of Wild Lilac Lane and Selene Court, east of Fountaingrove and over a blazing ridge, near the Rincon Valley Christian School off Brush Creek Road. A reporter arrived, following the smoke, and no roadblocks had been established by law enforcement.

From a cul-de-sac in this neighborhood of high-priced homes—many with Spanish-tile roofs and many burned to the ground—one could watch fires popping up in an almost a 360-degree arc around the region.

Mike Alderman came running down Wild Lilac with a big wrench in his hand and sporting a Red Wing Boots T-shirt. Alderman is a plumber who came to Selene Court to check on his ex-wife, who was fine. He stayed behind to shut down gas lines on homes that had escaped the flames. It seems miraculous that any did escape, and created a jarring juxtaposition against neighbors’ homes that were reduced to smoldering ruins.

The gas also ignited small fires which started creeping toward houses that had escaped the flames. Eventually, a small out-building went up in flames and the son of the owner showed up from Sacramento to check out the destruction. He snapped photos on his phone and sent them to his parents, then distributed some water bottles and left.

Cal Fire trucks made a few passes through the area over the course of several hours, keeping a watchful eye on this little section of hell, and a California Department of Corrections fire crew was busily fireproofing another house that had escaped the wrath of Tubbs. They scratched dirt around and broke out the chainsaws to save the house, which was totally surrounded by destruction and on the neighboring lot.

A pool at one destroyed home was filled with water and the lawn furniture and colorful canvas umbrella had escaped the blaze, somehow.

Adding to the horrors of Monday night was the fate of the 200 patients who had to be evacuated from Kaiser Permanente and Sutter hospitals. Shawna Marzett, a patient-care technician at the hospital, said Kaiser was admitting ambulances bearing fire victims until early Monday morning until the fire bore down on them from the hillsides above, and then it was time to evacuate.

“Looking through those big glass windows you could feel the heat,” she said. “We had doctors and nurses watching their homes burn while they were helping.”

She and the staff went room to room, wheeling out patients with IVs and babies from the intensive care ward and then slapping “empty” signs on the rooms when everyone was safely out. In about two hours, the hospital was empty.

“Kaiser did an amazing job getting people out,” she said.

Patients from Kaiser and Sutter were bused to Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital and neighboring facilities. A hospital spokeswoman reported that about 170 patients had come through with fire-related injuries by Tuesday, far lower than anticipated. Most were treated for minor burns or smoke inhalation and released, though a dozen patients had more significant burns and four had to be transferred to burn centers.

On Monday night around rush-hour, Highway 101 was choked with smoke and traffic, and dozens of lights blazing atop ambulances were headed north on the highway into the pop-up inferno zone.

The firestorm was prompted by very low humidity (11 percent) and very high wind gusts. The wind had died down Monday, but Tuesday forecasters warned that offshore winds were picking up again and would blow 25 to 30 miles an hour from the northeast on Tuesday night.

Williams at Cal Fire says firefighters have “worked diligently at the southern end of the fires,” to build defenses to prepare for the windy prediction.

Vice President Mike Pence was in Sacramento on a previously scheduled trip and he gave a press conference on Tuesday focused on the fire and the federal response. President Trump had just approved a disaster declaration, which means funds from the Federal Emergency Management Agency are on the way. Pence spoke for many when he highlighted the work of first responders.

“Cal Fire is inspiring the nation, and we stand with them with great admiration and appreciation.,” the vice president said as he assured the North Bay that “more assets are on the way.”

There are currently at least 600 fire personnel and 84 engines fighting the Tubbs fire, with assets drawn from the Cal Fire mutual-aid ranks of San Diego to the Oregon border.

[page]

OCTOBER FIRES

A bitter end to the 2017 vintage

Grieving the loss of wine is no frivolity in a time like this, when you consider the dreams and long years of work that built the wineries and vineyards damaged and lost in the fires that swept through Napa and Sonoma wine country this week, not to mention the livelihoods of the many residents employed in the business of making wine—even the good memories that wine lovers have of spending time at these places and the moments shared with their wines.

And after the day that I spent rototilling some semblance of a fire break while watching two plumes advance on either side of my family’s property, I have to report that a still-cool glass of rosé wine was quite welcome.

This is what we know so far about the wineries affected by the blaze:

Paradise Ridge Winery, opened in 1994 by Walter and Marijke Byck and beloved for its views, sunset winetastings, Nagasawa historical exhibit, and sculpture garden, has been destroyed. The newly designated Fountaingrove District was hit particularly hard by the fire as it swept from Calistoga over the hill and through Santa Rosa neighborhoods. Just below, winemaker Adam Lee says that Siduri survived. “A minor miracle,” Lee reports. “Things burned on all sides of it.”

The big custom-crush operation Punchdown Cellars, where many small wineries get their start in the business, remarkably is still standing amid a scene of devastation in North Santa Rosa, according to Suzanne Hagins of the organic-focused Horse & Plow. “Not sure the fate of the wines currently fermenting,” says Hagins, “but it sure seems unimportant in the face of all this.”

On Silverado Trail in Napa Valley, photos of Signorello Estate Winery document that it went up in flames.

In nearby Napa’s Stags Leap District, staff reports that White Rock Vineyards is gone, while an initial report of the loss of historic Stags’ Leap Winery was not correct. As of Tuesday, wine associations were hesitant too. “We’ve all been collectively concerned with each others’ well-being and property,” says Stags Leap District Winegrowers Association director Nancy Bialek, in a statement. “There has been much texting but damage has not been fully assessed as the Trail is closed. I do know vintners fought through the night to fend off flames and evacuate all.”

Separate fires threatened the grassy slopes of the Carneros district. “Right now the fires remain in Carneros, and we won’t know the impact of the fires until we can assess the damage,” says Carla Bosco, Carneros Wine Alliance board chair. “Our two local fire crews, Carneros and Schell-Vista, have been amazing in protecting Carneros and we are grateful for their diligent work. We are ready to help those in need when we get the clearance to go back in.”

It’s worth mentioning that while some have said that vineyards are a natural firebreak, it depends on whether the soil was tilled under or not—and other factors. St. Francis Winery reported that fire damaged some vineyards, while the winery stands. Early reports that picturesque Chateau St. Jean was burned were not correct. Meanwhile, the Nuns fire still threatened to jump the ridge back toward Napa on Tuesday afternoon.