HELPING HANDS Jenny Harrow and JoEllen DeNicola of the Integrative Healers Action Network sign up evacuees for alternative therapies at the Kenilworth Recreation Center.

HEALING HANDS Dr. Brian Bouch provides acupuncture to a shelter patient in the alternative medicine room.

Wind gusts blow dense streams of dry leaves across the quickly filling parking lot at the Petaluma Veterans Memorial Building. The location is one of many evacuation shelters available to some of the more than 180,000 evacuees from Santa Rosa, Geyserville, Healdsburg, Windsor, Sebastopol and more locations extending all the way out to the California coastline.

Up to 187,000 people have now been evacuated from Sonoma County, where over 75,000 acres of land has burned and still burning with only a 15 percent containment as of this reporting.

Inside, dozens of cots with exhausted people and their belongings fill the room. Breakfast tables and the last of the morning’s diners fill the next hall over. Organizers are staffing tables checking people in. More people arrive by the minute.

Evacuees’ emotions range from stressed to going-with-the-flow. April and Todd Axberg, both nurses at Kaiser Permanente and Santa Rosa Memorial respectively, arrived Saturday night from Santa Rosa. They camped out in their truck in the Petaluma Veterans Building parking lot with their dogs.

“I’m a veteran and ironically it’s the first time I’ve used the Veterans facility,” says Todd Axberg. Their former Mark West Springs home burned down in 2017 and they lived in a trailer for seven months while rebuilding. They have lived in their new home for about a year now.

“We already knew generator life, so we were fine with the outages,” he adds. “But when the wind started picking up we were acutely attuned to it.”

“We put a lot of work into the house but we don’t have a lot of connections there this time so it’s different from before,” says his wife, April Axberg, of leaving their home in the wake of fire danger.

The volunteers are busy and kind. One volunteer at the shelter said it was getting to capacity, but they weren’t turning people away. The city of Petaluma released a statement Sunday that the County of Sonoma has arranged for more shelters throughout the region. The city is also working with faith-based and nonprofit partners to open additional shelters on an ongoing basis to accommodate the many in need. Volunteers or donations can go through Petaluma People Services Center to ensure that evacuees and first responders receive what they need in the most organized and sensitive way possible.

Margery Egge of Healdsburg describes the surreal evacuation process, “I couldn’t believe how peaceful it was, you just watch your neighbors leave one by one,” she says.

Eventually she and her husband Ross Egge also left in their trailer and are now parked at the AMF Boulevard Lanes next to the Petaluma Veterans Building, which is near their daughter’s family.

Ultimately, the mandatory evacuations in potential fire danger zones made things more orderly for law enforcement and for people leaving their homes, according to some volunteers at the shelters.

“It’s not as hectic as last time,” says Morena Carvalho, a volunteer at the Sonoma-Marin fairgrounds shelter. “It’s much more calm.”

While many evacuees can go stay with friends or family nearby, or take their RVs to safety, many more must stay in the evacuee shelters set up all over the Bay Area. For many of the evacuated, life was already difficult. Immigrant communities and people of color, in particular, experience additional impact in these kinds of emergency situations including immigrant Latinx women who make up much of the home care, domestic, healthcare and hotel worker community.

“When fires hit, they are the most vulnerable,” says Mara Ventura, Executive Director for North Bay Jobs With Justice, which advocates for workers’ rights, “And for a lot of undocumented workers, a big impact is lost wages.”

One such group is home care workers.

“Many home care workers have been displaced,” explains Ventura. “Some are going with clients to the shelter, or they are home without electricity. Often, their clients are with their families during an emergency like this.”

Another impact is the fear of seeking services due to immigration issues. That said, U.S. Rep. Jared Huffman said today that they received official assurance form the Department of Homeland Security that “Everyone seeking services or shelter from the immigrant community should do so with confidence that there will not be immigration enforcement activity.”

Additionally, while uniformed Sonoma County probation officers are at the Veterans Center, they are only there to help with providing additional security and not to ask anyone questions. “We don’t want to cause any more stress, we’re just here to help with security,” one officer affirmed.

Other obstacles include the reality that for undocumented families, federal help is not available. For those families, Undocufund Fire Relief provides assistance to those who can’t otherwise receive help. According to their website, after the 2017 fires, Undocufund “distributed almost $6 million to undocumented families in Sonoma County impacted by the fires to support them in recovering and rebuilding their lives.”

Ventura is part of a network of community organizers who work with communities of color started by Criminal Immigration Specialist, Deputy Public Defender Bernice Espinoza as a Facebook group. She created it to coordinate services for immigrant and Spanish-speaking groups, especially in emergency situations when they can fall through the cracks.

“We can communicate needs we’re seeing in the places we’re working, we can put a call out to the network for what is needed, from bilingual services to culturally competent food,” explains Espinoza. Culturally competent food refers to the fact that many individuals won’t eat food outside their ethnic upbringing that they aren’t familiar with, and need more explanation before they feel comfortable with it.

The network is now coordinating bilingual volunteers and childcare for families at shelters, as well as a comprehensive list of volunteers.

“Our biggest role right now is compiling a master volunteer list, mostly bilingual people—not just Spanish—whom we’ve been dispatching to the shelters,” says Ventura.

The network of organizers is also coordinating with the local Methodist church to ensure that the latest information gets to the homeless since they don’t always have smartphones.

Cities and organizations are much more in synch this time around, thanks to work done in the aftermath of the 2017 fires.

“There were many good lessons learned during the 2017 fire, but it was hard to coordinate then. This time it’s been so much more connected. I really appreciate it and hope that in the debrief of this fire we plan to be even more coordinated with community organizations and county efforts.”

Approximately 4,000 customers have lost power, mostly on the west side of the city. Another similar wind event beginning early Tuesday morning on Oct. 29 could lead to even longer power outages.

Ana Paladi from Romania and Jarkko Hartikhainnen from Estonia are interns at the Michael David Winery in Cloverdale, “We arrived in August to work” says Hartikhainnen. “Right now we’re staying with friends from work on an air mattress on the floor. What can you do about it?”

They are two among many young interns who chase the wine harvests across the world, working in countries as far flung as Chile, Brazil, and Australia.

“I was riding my bike to work at 4 a.m. in the dark and could see the fire on the horizon and the helicopters working hard, they were like bees in a field,” Hartikhainnen says.

Even after the fire ends, volunteers are still needed. There is a need for so many things, including people to do cleaning, night shifts, child care and entertainment, as well as therapeutic and bilingual volunteers.

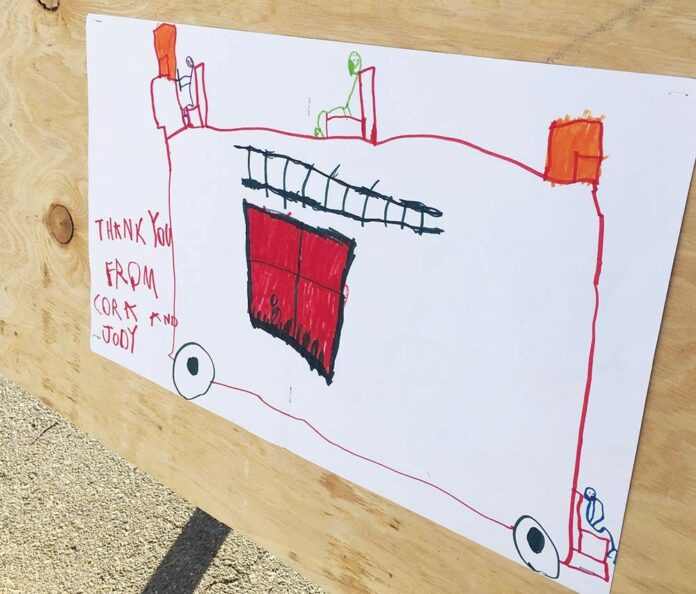

At the Kenilworth Recreation Center in Petaluma, cheerful volunteers sort through the many donations, cook food and check people into the alternative healing room, where evacuees can receive acupuncture, massage and other therapies to help with trauma. Across the street in the shelter, volunteers are doing art projects with children and giving them ukulele lessons to distract them and help pass the time.

“The shelters may be around for weeks or even months in the aftermath,” says Ventura, “and we need to have as large a list of people as possible so we can make sure volunteers have adequate rest and are able to have their normal lives too.”