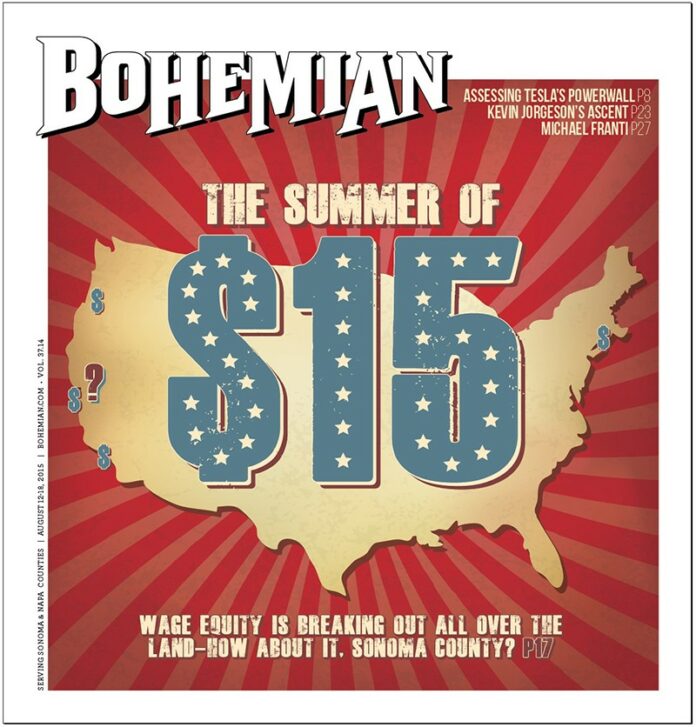

The summer of 2015 is also the summer of $15. In cities and states around the country, underpaid workers have broken through political inertia and corporate pushback to help bring wages to a semblance of decency. In Los Angeles, city leaders passed a $15 an hour minimum wage that’ll phase in over the next few years. San Francisco did the same, following on Seattle’s living-wage ordinance, and in New York, a state wage board has taken the remarkable step of advocating that big-time fast-food restaurants pay a $15-an-hour wage.

New York governor Andrew Cuomo has accepted that recommendation, even as Dunkin’ Donuts warns of total catastrophe, a massive doughnut hole in the company’s profit margin, layoffs and the whole fear-mongering shebang you’d expect.

A compliant business press, led by Forbes magazine, is now predictably rolling out articles that speak of the hidden dangers of the fight for $15: It’s a job-killer! Closer to home, a bill to raise the state minimum wage to $13 an hour by 2017 has languished in the assembly after passing out of the senate. Gov. Jerry Brown opposes it. Under a previous bill, the state minimum wage will rise by a buck, to $10, on Jan. 1.

Meanwhile, Walmart, the behemoth of fine Chinese products, has slowly raised its wages to around that same California minimum in the face of relentless pressure from activists. Sen. Bernie Sanders is calling for a doubling-plus of the federal minimum wage, from $7.25 to $15 an hour.

Yet the buck stops here in Sonoma County for a large group of workers not covered under a county living-wage ordinance under consideration by the supervisors. The supervisors have been under a relentless wave of wage-hike agitation from the coalition North Bay Jobs for Justice and have steadfastly refused to raise the rate to all who would labor under the county’s bosom.

County workers who aren’t already earning a living wage (custodians and other blue-collar workers, mainly)—they’re covered. Contractors with county business are also covered, but they don’t have to raise the wages of county-contracted workers until their contracts are re-signed or amended. Living wage activists also point to a group of airport workers excluded from the ordinance, as well as concessionaires who, for example, work at the Sonoma County Fair. And then there’s that big bloc of critical workers: thousands of in-home supportive service (IHSS) workers stuck at $11.65 an hour.

Marty Bennett, an organizer and spokesman with the organization North Bay Jobs for Justice, calls the proposed ordinance “the most ineffective, least comprehensive living-wage ordinance ever passed.”

The supervisors pushed off a living-wage agenda item for another day on Aug. 11, but IHSS workers showed up in force anyway to protest in front of the County Administration Building.

They are not letting it go in this summer of $15.

In some measure, the wage fight in Sonoma County finds civic leaders caught between the forces of an unfolding and historic moment for workers across the country, and a county whose own public persona is progressive and eager to lead on issues like climate change, “sustainability” and other national concerns.

A county-commissioned study by the Oakland-based Blue Sky Consulting Group noted late in 2014 that, because of the outsized costs that get passed on to localities by the IHSS workers and then on to taxpayers, “most counties in California with living-wage policies exclude IHSS workers.” So why should Sonoma County seize the IHSS initiative when nobody else in the state is doing so?

Marin County has done so, and raised its wage for those workers to $13.10 an hour, says Bennett. Ditto San Francisco, which passed a living-wage ordinance following on a local referendum—and included that city’s IHSS workers.

The living-wage ordinance under consideration by the Sonoma supervisors also includes in its scope “franchisee” contractors that do big business with the county.

That includes, for example, the Ratto Group and Republic Services. The latter is one of the country’s largest waste-management firms, and now runs the county-owned landfill and five garbage-transfer stations. The Ratto Group picks up much of the county’s garbage and recyclables.

[page]

Under the terms of the Sonoma County living-wage ordinance, county spokeswoman Rebecca Wachsberg says, both companies would be on the hook to pay their county-affiliated workers $15 when contracts are re-signed or amended.

The catch: It could be a while.

Sonoma County Transportation and Public Works director Susan Klassen says there are two contracts split between the respective companies. “There is the master operations agreement with Republic Services for operation of the county landfill and transfer stations,” she says via email. “It was originally approved by the board in 2013, but became effective in April 2015. The term of the agreement is technically for the life of the landfill, estimated to be greater than 25 years. The Ratto group is a subcontractor to Republic Services in this agreement. They provide operations for the transfer stations.”

The other contract, says Klassen, is a “county franchise agreement for curbside and commercial collection of garbage and recycling in the unincorporated county. It is with the Ratto Group. It started in 2009, and ends 20 years later, in 2029.”

So one contract is for at least 25 years and the other is for 20. Wachsberg, however, says that “the chances of their not being amended is not very likely” over the duration of the contracts.

Ratto Group spokesman Eric Koenigshofer says the company hasn’t taken a position on the ordinance. “We’re neutral on it, and as far as I know, we are subject to it.” He says that a “brand-new, day-one employee on the recycling line [starts at] $9.50.”

But Ratto workers’ wages climb into the $24-an-hour range for drivers, and, says Koenigshofer, the company offers everyone a health plan after 90 days with no employee contribution beyond a nominal co-pay. Depending on the employee’s family situation, he says, that can translate into between about $600 and $1,800 a month worth of benefits paid by the company. “It adds a lot to the total compensation,” says Koenigshofer.

Carol Taylor is an IHSS worker who lives in the town of Sonoma and has been fighting for better wages for herself and other workers for a long time. She’s been in the business for 14 years—”This time around,” she says—and first started doing the in-home care work when her husband was sick. “I nursed him until he died,” says Taylor, who went on to study nursing for a while before returning to the IHSS fold.

Taylor also has an accounting degree but would rather help people in need than do people’s taxes for a living. She says that this work is “really a calling for me. People ask me, ‘You have an accounting degree, why are you wiping behinds for $11.65 an hour?’ Because I like it.”

[page]

The $11.65 wage paid to IHSS workers was the supervisors’ attempt at wage equity in the face of a determined push for $15 that has failed to gain traction. The supervisors raised their rate by 15 cents in 2013, and even that was no easy task, says Taylor. “We bargained for three years for the 15 cent raise.”

County supervisor David Rabbitt recently told the Bohemian that the annual county IHSS budget is around $13.5 million, and that the county “struggled to find the 15 cents to add” to get it to $11.65.

Taylor understands that, from the county’s perspective, raising the IHSS wage by more than $3 all at once to $15 is a tall order. The workers are licensed by the state and operate under the aegis of a state program, the Coordinated Care Initiative, which was created in 2012 to help manage a growing industry of in-home workers, a critical cadre of healthcare employees engaged in eldercare and care for the developmentally disabled.

It’s not easy work, says Taylor, though it is rewarding. The hours, she says, are oftentimes a “crazy quilt where you work two hours here, three hours there. It’s not a 9-to-5 job.”

Another problem for the workers is that there’s a rolling critique of the industry as a whole that’s a legacy item from the administration of former governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. The Governator’s infamous take on IHSS workers was that this was the sort of work families should be doing on their own dime, not the state’s.

“I don’t know about [Gov.] Brown,” says Taylor, “but [this mindset] is still the biggest obstacle.”

“People do have to stop and think about this,” she adds. “Gone are the days where there’s a single family earner. And the reality is, we do lots and lots of work with autistic kids. Social workers say that family members work far more hours than nonfamily caregivers—they take care of them for a lot of hours that we’re not getting paid for. Most of us don’t have grandma waiting in the wings; that’s part of what our society has become.”

But Taylor does admit that the county “doesn’t really have control over the number of workers or the number of hours they work. It is kind of a blank check, but it’s one that Marin County was willing to sign.”

The Blue Sky Consulting Group report, for which the county paid $90,000 and based its ordinance around, recommended that Sonoma County leaders continue to set IHSS worker wages “through existing collective bargaining practices” with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU)—and that’s been the county’s posture.

Blue Sky also set the stage for what critics charge is a county punt to the state; by 2018, wage negotiations for Sonoma County IHSS workers will shift to the state.

In studying the potential budgetary impact on Sonoma County, Blue Sky found that “at a wage rate of $15 per hour, the total cost to the county for the living-wage ordinance would be an estimated $12.3 million annually,” the report determined. “Most

of this cost, $11.2 million, or

91 percent, would be attributable to IHSS providers.”

Blue Sky also highlighted the state-county relationship on this issue, and essentially provided cover for the county to push the IHSS question to the state and SEIU negotiators, which will occur across the state under the Coordinated Care Initiative.

To wit: “It is anticipated that the state of California will take over collective bargaining with IHSS providers beginning in 2018,” says the Blue Sky report. “However, until this occurs, the county will be responsible for determining (and paying for) the amount of any pay increase for these workers, and any additional increases provided prior to the state taking over will be borne solely by the county and the federal government, with no state contribution, even after the state assumes negotiations responsibility” (emphasis added).

In other words, it would appear to be in the interest of budget-conscious Sonoma County supervisors to keep IHSS wages as low as possible until 2018. According to the Blue Sky report, any increase they agree to between now and then will be charged to the county and can’t be laid off on the state or feds.

[page]

In a recent interview with the Bohemian (see “House of Payin’,” June 24), Rabbitt told the paper that he agrees IHSS workers are underpaid, “and the reality is, yes, it’s a state issue.”

But even if, as the Blue Sky report claims, most counties in California with living-wage ordinances don’t include IHSS workers in their scope, Bennett says that San Francisco included those workers when voters there passed a countywide minimum-wage ordinance in 2014.

In a June 28 letter to the Sonoma County supervisors, Bennett took them to task for ignoring the very recommendations the county itself made in its 2014 report “A Portrait of Sonoma,” which, he wrote, “recommends that the county ‘ensure that all jobs, including those that do not require a college degree, pay wages that afford workers the dignity of self-sufficiency and the peace of mind of economic security.’ The report explicitly calls for building upon other living-wage ordinances implemented in the county to ‘raise the wage floor further.'”

Instead, wrote Bennett, “the proposed ordinance exempts far more workers from the $15-an-hour wage than it covers.”

County leaders have taken the position that there are other ways to lift people out of poverty besides raising wages to $15—an emphasis on early education, affordable housing and the like.

Twenty fifteen is also shaping up as a year of pre-primary posturing on the national political front. Most of the Republican contenders for president are, unsurprisingly, not in favor of raising the federal minimum wage, and a few of them would outright abolish it. Talkin’ to you, Scott Walker.

Ralph Nader offered up a useful article on the Huffington Post in June that surveyed the field: Only GOP candidates Rick Santorum and Ben Carson have made positive gestures in the direction of a higher federal minimum wage—sans detail, of course—and Donald Trump says he’d create two minimum wages: one for youth, and one for everyone else. Of course there wasn’t a peep about the fight for $15 during last week’s debate on Fox. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, has supported a $10.10 federal minimum wage since last year.

OK, let’s say unicorns are real, Bernie Sanders is elected president, and his first order of business is to push congress to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. Or let’s say the Sonoma County supervisors decide to just go ahead and pay those IHSS workers $15, budget be damned. Stranger things have happened.

Unfortunately, even at $15, those IHSS workers are still living in poverty, unless they take Jeb Bush’s advice and work 80 hours a week—which is what a lot of working people already do to make ends meet, so thanks for that, Jeb.

A person working a humane 35-hour week at $15 an hour earns a pre-tax annual income of $27,300. For a family of four, $27,300 is about $4,000 a year above the national poverty line, but don’t book that reservation at the French Laundry just yet.

The Pew Research Center issued a study in late July that looked at the impact of the national push for $15 to see how effective it would actually be at lifting people out of poverty. Surprise, surprise: $15 an hour doesn’t go nearly as far in the North Bay as it does in, say, the Confederate state of Alabama.

The organization researched the buying power of $15 in all 50 states, got granular on a region-by-region basis and found that in our neck of the woods, $15 an hour translates to about $12 worth of buying power. We pay a premium for all this natural beauty and ace weather in high food costs, ridiculous rents and eye-popping costs at the gas-gouger’s station.

But wait, it gets worse.

The Pew study came on the heels of another from early June that this paper reported on at the time, from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, “Out of Reach: Low Wages & High Rents Lock Renters Out Across the Country.” The study found that California rents average $1,386 a month for a two-bedroom apartment. Santa Rosa rents average around $1,370, but as we reported back in June, Sonoma County rents are generally on the rise; the countywide average is $1,624 for a two-bedroom. To pay that rent without blowing more than 30 percent of your paycheck, you’d have to be making $26.65 an hour.

That’s a far cry from $15 an hour, and an even farther cry from the $11.65 people like Carol Taylor are earning.

Hey, here’s a thought: Anyone up for making the summer of 2016 the summer of $26.65?