On Monday, Oct. 1 it was announced that Dominican-American author and Pulitzer Prize Winner Junot Diaz had been given a 2012 MacArthur “genius” award, a $500,000 no-strings attached grant to “talented individuals who have shown extraordinary originality and dedication in their creative pursuits.”

Diaz has received acclaim lately for his newest short story collection, This is How You Lose Her, released by Riverhead Books in August. His 2007 novel, The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao is considered to be one of the best books of the 21st century. It’s always at the top of my list of recommended books for a brilliant take on a sci-fi nerd turned wannabe lothario doomed by familial and socio-political history.

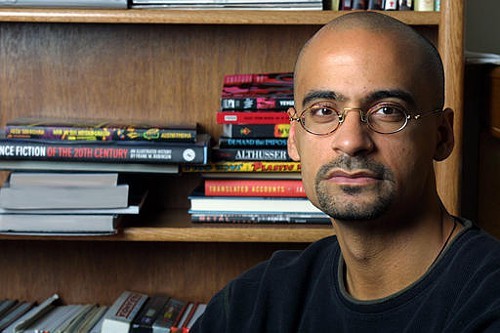

Here’s our interview with Junot Diaz, part of a Sep. 5 Arts Feature that came out right before Diaz’s packed appearance at Copperfield’s Books in Montgomery Village. By the way, at that appearance, Diaz was asked the question, “If you could be any other writer, who would you be?” In a fantastic subversion of expectations, Diaz said that he would be Octavia Butler, the African-American science fiction author of such classics as Parable of the Sower and Kindred. It was a beautiful moment in the history of literature.

How does the idea of apocalypse play into your current project and your work in general?

As far as the apocalypse, I grew up in the most apocalyptic area in the world. We can’t think of a place that has endured more apocalypses than the Dominican Republic and the island of Hispaniola, or the island of Haiti has endured everything expect for a nuclear catastrophe. I think these shadows, these historical echoes reached me and they both intrigued and troubled me. And I came up in New Jersey, within slight distance of New York City during the time of the possibility of total nuclear annihilation. I was one of those kids that grew up in a time where you would see, on the news, they’d suddenly flash a map of New York City and they would show a big black ring, of every area, every town, every person within that range would be utterly obliterated, and of course, we were deep in the heart of that ring.

The apocalyptic history of both the Dominican Republic and the United States has resonated with me and continues to shape a lot of the interests in my work.

I grew up in the 1980’s and remember being terrified by movies like “The Day After.”

I mean, that stuff just blows your mind. You’re like, “What the fuck!”

I don’t think it ever leaves you. That feeling of everything could end right now never really goes away.

These are things that, again, you learn in your childhood how to dream. We think that we just get dreaming built into us, that it’s something that comes natural. But, the shape and the content of our dreams is acquired in our childhood and I think it’s no accident that people like me and you have a strand to our dreams that’s apocalyptic. How could you not growing up that way? It’s not only Sarah Connor that dreams of the world exploding. We are all basically Sarah Connor’s children.

She’s the one from The Terminator right?

Yep, that’s how nerdy I am, girl.

(Diaz shows the film in a post-apocalyptic literature class that he teaches at MIT. He also shows “The Day After,” the 1980’s nuclear catastrophe made-for-TV movie. )

In this book that I just wrote, the character’s actually a conversation about The Day After. And in fact, in the story “Miss Lora,” the narrator Yunior dismisses The Day After as nonsense, and talks about how he prefers the more hardcore British movie Threads.

It took you 10 or 11 years to write “The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” and it seems like it was a fairly grueling process, not writing that writing a novel is ever easy. In comparison, what was the process of writing the stories in “This is How You Lose Her?”

It me took 17 years to write these. You can safely say that this was not an easy tow. I’ve pretty much been living them for a very long time. They’re kind of braided together, in a way, with my last book.

In an interview with Paula Moya for The Boston Review, you said about black women writers, “Why these sisters struck me as he most dangerous of artists was because in the work of, say Morrison, or Octavia Butler, we are shown the awful radiant truth of how profoundly constituted we are of our oppressions.” Do you do this in your own work? I’m thinking specifically of the stories in “This is How You Lose Her.” Are Yunior, Rafa and the narrator of “Otravida, Otravez” profoundly constituted of their own oppressions?

Oh god, that should be up to the reader to say, you know? I’m always very wary of explaining what I write because, I think that’s a great question, but I think that you would be better at answering than I would be. I do think that in the end it’s the reader that has to answer that question and not the writer. I raised the question, so custom dictates that the reader would the one to respond now. I really do understand the value and the merit of the question and as a writer I don’t want to be completely coy. I mean, to direct our attention to the most obvious, look at the way that Yunior’s sexism and his hetero-normative, patriarchal, master-of-the- imaginary leads him to view women as not fully human. Gee whiz, this engages and involves him in every aspect of his life. And it is as much of an oppression that he produces as he produces that produces him.

And traps him in his own misery

Without any question.

But that can make the stories difficult to read in a way too. I was talking to a friend of mine about how I was reading your new collection and she told me that she couldn’t read your books because of the way that women are represented. She said that it’s just too painful for her. The references to “bitches” and “ho’s” made me wince at times.

That’s just strange because that would be like, none of these people have every spent any time in the public sphere of America or listened to hip hop. Or have never listened to a politician, or don’t live in this culture. I think what’s happening here is that we’re far more comfortable living our oppression as long as no one represents it to us in art. In other words, the fact that you guys are not around this shit all the time, and I mean ALL THE TIME. I think the difficulty is that we are so unaccustomed, we live basically in the emperor’s new clothes, where we’re undergoing this oppression, but we all sit around and say, “No, we’re not.” And then what really excruciates us, what shocks the shit out of us is when somebody makes the mistake of pointing out that the emperor has not clothes. Or when somebody makes the mistake of saying, “Hey, this is what’s happening to us.” We’ve gotten super twisted as a society. It’s really fascinating. If you think about the 60’s, you didn’t surprise or shock anybody in America, white, black, brown, yellow to say that there was racism in America. White people would have been like, “Yes, there is racism and we want more.” You know? Now, if you say that there’s racism in this country, every single person will try to silence you. Everybody will be like, “No, that’s not true.”

I can’t speak for your friend, I’m sure she just thinks I suck at it and that I’m not just simply representing, that I’m approving of this stuff. I would disagree. I think that people confuse representation with approbation. How can you even be in the conversation if you avoid it? What I’m specifically saying is that, we’ve gotten into a very weird place in our culture where I think most of us are deeply avoidant of the kind of conversation that would be required to, in many ways, alter or improve our situation. Because to alter and improve our situation literally means looking into the abyss.

The hardest thing to do is to live our oppression. It’s not to encounter it in art. It says a lot about how much pain we must be undergoing, that to encounter oppression in art is unbearable.But I know that fear, I know that agony. I think that we’re in a space where there are not many spaces of deliberation; We’re not accustomed to them. We didn’t grow up with these expressions and certainly the culture has done everything possible to bend us away from them.

It’s almost like the classic, you have to be able to hold two opposing ideas at the same time, in reading the stories in “This is How You Lose Her.” This is a representation of something that’s real. This isn’t made up, but that’s not necessarily saying that it’s right.

I think it’s no accident that the people who do the best job of reminding us of our oppression are artists. And that the one area of our education that has been most systematically gutted in this country is arts education. It’s no accident that people confuse representation with approbation. It’s almost like a natural leap for most people. They’re like, “Oh, he says the word ‘n****r’ must mean he completely agrees with it.” I think that there’s a deep connection. There’s something about art that really engages us in questioning our social lives.People’s lack of arts education has taken out a lot of our teeth.

In terms of activism, how do you balance those two? How does your activism feed into your art or are those two things separate?

I look at people like Maxine Hong Kingston. She’s been a long, long-time peace activist and she’s one of the most important writers. I look at Sandra Cisneros. Sandra Cisneros has been a very active member of the Chicana feminist community and she’s been able to do it. It’s the same question as “Can a woman work and have a family?” For me, we’re always being told that these things are mutually exclusive, that you’ve got to choose one or the other. But you know, I’m always being asked to choose between categories where I would never choose one or the other. I would always choose both. Arts and activism for me is a natural. Being of African descent, being from the Caribbean and being Latino. Anytime I’m asked to choose one, I look at the person and say, “I totally fucking reject your request.”

It’s like an inability to understand, at least in the United States, the ability to exist in-between.

Yeah and simultaneous. Often in-between, there’s something skulking a lot of times when I hear the term in-between. I think there’s always this either/or but for me it’s like, how about both?

Final question: Will Yunior ever find decolonial love?

I think the book asks the reader at the end. I think the book makes some very strong claims about his journey, about what he learned. I guess you read the book, and by the end it asks, do you think he’s changed enough where that’s possible? It would be too simple to show Yunior at the end meeting someone on a park bench and going, “Wow, here’s the future.” Instead, I leave Yunior at the cusp of transformation and I ask the reader, “Well, is he a different person than the person who opens the book saying, “I’m not a bad guy?” The book doesn’t end with Yunior saying “I’m not a bad guy.” It’s up to the reader to write that final chapter.