In July, roughly 1,000 rural Sonoma County residents overflowed classrooms and small meeting chambers at five informational sessions convened by the State Water Resources Control Board. It would be hard to exaggerate many attendees’ outrage. At one meeting, two men got in a fistfight over whether to be “respectful” to the state and federal officials on hand.

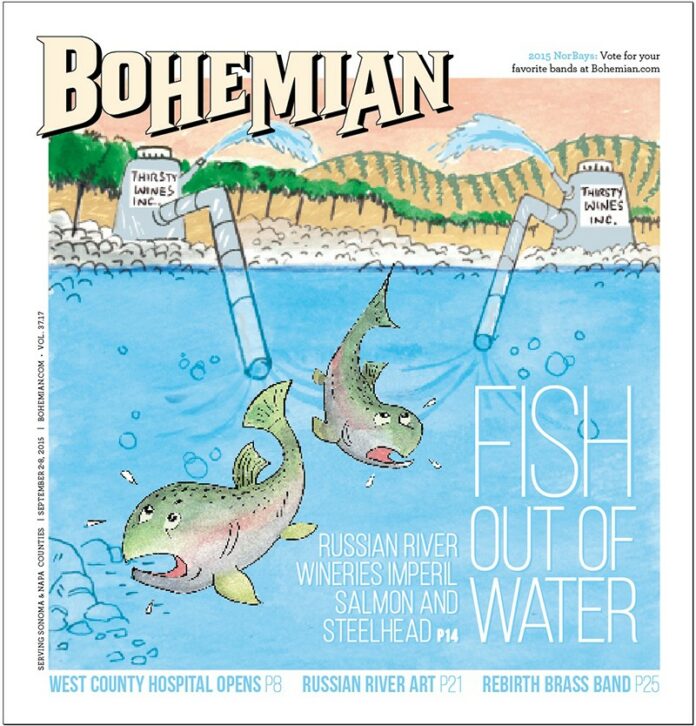

The immediate source of their frustration is a drought-related “emergency order” in portions of four Russian River tributaries: Mill Creek, Mark West Creek, Green Valley Creek and Dutch Bill Creek. Its stated aim is to protect endangered coho salmon and threatened steelhead trout. Among other things, the 270-day regulation forbids the watering of lawns. It places limits on car washing and watering residential gardens. It does not, however, restrict water use of the main contemporary cause of these watersheds’ decline: the wine industry.

“The State Water Resources Control Board is regulating lawns? I challenge you to find ornamental lawns in the Dutch Bill, Green Valley and Atascadero Creek watersheds,” said Occidental resident Ann Maurice in a statement to the water board, summing up many residents’ sentiments. “It is not grass that is causing the problem. It is irrigated vineyards.”

In what many see as a response to public pressure, the Sonoma County Winegrape Commission, an industry trade group, announced last week that 68 of the 130 vineyards in the four watersheds have committed to a voluntary 25 percent reduction in water use relative to 2013 levels. According to commission president Karissa Kruse, these 68 properties include about 2,000 acres of land.

Sonoma County Supervisor James Gore, whose district encompasses more Russian River stream miles than that of any other county supervisor, has been strongly involved in developing the county’s response to the water board regulations and was the only supervisor to attend any of the state’s so-called community meetings.

“I applaud the winegrowers for stepping up,” Gore says in an interview. “I think they saw the writing on the wall. They knew they weren’t going to continue to be exempt from this sort of regulation for long, and there are also winegrowers already doing good things in those watersheds who wanted to tell their stories.”

Initially, state and federal officials who crafted the regulation said they preferred cutting off “superfluous” uses as a first step. “Our target is not irrigation that provides an economic benefit,” says State Water Resources Control Board member Dorene D’Adamo of Stanislaus. D’Adamo has been the five-member board’s point person for developing the regulations and was appointed by Gov. Jerry Brown as its “agricultural representative.”

Many residents argue that there is no way of monitoring the vineyards’ compliance with the voluntary cutback because their water use has never been metered. Moreover, these residents’ passionate response to the regulation did not emerge in a vacuum. Rather, it tapped a deep well of resentment regarding the long-standing preferential treatment they say state, county and even federal officials have accorded the powerful, multibillion dollar regional wine industry.

As longtime Mark West Creek area resident Laura Waldbaum notes, her voice sharpening into an insistent tone, “The problem in Mark West Creek did not start with the drought.”

A RIVER RAN THROUGH IT

As California lurches through its fourth year of an unprecedented drought, it is no surprise that long-simmering Russian River water conflicts have come to the forefront. At the center of this struggle are salmon and trout, whose epic life journeys play out on a scale akin to Homer’s Odysseus.

Historically, the Russian River has been known for its runs of three different salmonids: coho salmon (which are federally listed as “endangered”), Chinook salmon and steelhead trout (which are “threatened”). All three fish are born in local creeks, or in the river itself, migrate to the ocean as they near adulthood and finally return to their natal streams to spawn and die.

As a growing body of scientific evidence indicates, salmon are crucial to the health of aquatic ecosystems, and their carcasses provide an enormous quantity of marine nutrients that can fertilize vegetation throughout a watershed. Much of the abundance of Pacific Northwest forests is traceable to the region’s salmon runs.

The mountains of Sonoma County are veined with streams that historically provided some of the Pacific Coast’s finest steelhead and coho spawning grounds and rearing nurseries. But the four horsemen of fisheries collapse—habitat degradation, dams, weakening of the genetic pool through the use of hatcheries, and overfishing—have taken an enormous toll. The destruction of ancient forests, instream gravel mining, the construction of the Warm Spring and Coyote Valley dams, and widespread agricultural development along waterways are among the main culprits. Overall, says National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) biologist David Hines, the river has devolved into “a basket case.”

“Some of the coastal streams in Mendocino County and further north have stronger fish populations because, even with the history of overlogging, the land hasn’t sustained as much damage,” Hines says. “In the Russian and San Lorenzo rivers [in Santa Cruz County], especially, much more of the habitat is simply gone.”

According to Fred Euphrat, a Santa Rosa Junior College forestry instructor who holds a doctorate in watershed management, the wine industry’s extraordinary expansion throughout the Russian River watershed in the last 40 years has been a major cause of the watershed’s enormous trouble.

“There’s been massive habitat destruction, habitat fragmentation, alteration of land and drainage water that delivers sediment to streams,” he notes.

The vast majority of regional vineyards are irrigated. Many use water from wells, an unknown proportion of which are hydrologically connected to the river. Others pump water directly from streams, creeks and the river itself.

[page]

Most of the vineyards in the Russian River’s lowlands are prone to frost damage. In spring, grape vines emerge from their winter dormancy with new vegetative growth that sprouts from buds established in the previous growing season. Frost can damage this new tissue and significantly affect the subsequent grape yields—and wine sales. Growers have increasingly sprayed water, via overhead sprinklers, on the vines to form a protective layer of ice over the new growth.

The amount of water that this practice requires, as Russian River grape-grower Rodney Strong noted in a 1993 interview with UC Berkeley’s Regional Oral History Office, is “horrendous”—typically, 50 to 55 gallons per minute, per acre. In 2005, University of California biologists documented up to 97 percent stream flow reductions overnight due to frost protection activities in Mayacama Creek, one of the Russian River’s five largest tributaries.

Frost-protection pumping in April 2008 led to dewatering on a scale perhaps unprecedented in the Russian River’s history. On several frigid mornings, winegrape growers diverted more than 30 percent of the river’s flow in Mendocino County alone, as measured at the Hopland US Geological Service gauge. The National Marine Fisheries Service estimated that 25,872 steelhead trout died as a result of frost-protection pumping in the upper Russian on a single day: April 20, 2008.

In response, the state water board moved to establish regulations on frost-protection pumping, albeit with the industry-friendly goal of “minimizing the impact of regulation on the use of water for purposes of frost protection,” according to a water board environmental impact report. The wine industry responded with an intensive lobbying campaign, punctuated by efforts from U.S. Rep. Mike Thompson of Napa—co-founder of the Congressional Wine Caucus and a Lake County vineyard owner himself—to forestall the regulations and question their scientific basis.

Close observers of county water politics say that such episodes have cowed regulators, since the wine industry wields considerable political muscle. Data I helped compile from California’s secretary of state showed that the California Association of Winegrape Growers and the San Francisco–based Wine Institute were two of the top five spenders among agribusiness organizations on lobbying California politicians in 2009 and 2010, when the frost-protection regulations were emerging.

“Regulators are under a lot of pressure to treat the industry with kid gloves,” says former Petaluma city councilmember David Keller, who is now the Bay Area director for Friends of the Eel River. “In the arena where the State Water Resources Control Board has jurisdiction, they’ve failed to strongly protect the public trust, although they are getting more serious. But the county has been missing in action on a lot of important issues.”

HEADWATERS

During the dry months, the Sonoma County Water Agency releases water from the Lake Mendocino and Lake Sonoma reservoirs (with much of the former consisting of water diverted from the Eel River) to ensure they meet the minimum stream flow in the river mandated by the state. In part, these minimum flows are designed to ensure fish survival.

The water agency supplies this water to the cities within the Russian River watershed, such as Santa Rosa, but also shunts these liquid resources across the Petaluma Gap via pipes to Petaluma and the water-starved towns of northern Marin County, which lie outside the Russian River drainage. This year, the agency has been under a requirement to reduce its diversions from the river by 25 percent in keeping with Gov. Brown’s emergency drought order.

This requirement does not extend to vineyards. Even if it did, there are few means to monitor the wine industry’s water use—unlike that of municipal residents—due to a lack of metering.

“We don’t have a countywide breakdown of water use for residences and agriculture,” says water agency spokeswoman Ann Dubay.

Having lived in the Russian River watershed for several years, I’ve been fascinated by the idea that Hopland and Ukiah grape growers had the capacity to reduce the Russian River’s flow by as much as 37 percent during an extraordinary 2008 frost-protection “event,” to borrow growers’ jargon. On July 15, two photographers and I set out on kayaks to document what these pumps actually look like from the perspective of the river.

Our 12-mile trip spanned only a fraction of the 110-mile river artery. Still, what we encountered was staggering. The most immediate problem we noticed is the extent to which river banks are eroding. By trapping sediment, dams force a sluggish river’s banks to erode. Lake Mendocino has caused so much erosion that the river channel has dropped by as many as 30 feet in some areas.

[page]

The number and size of the river’s diversion pumps are just as staggering. We captured photos of 27 diversion pipes that, as a conservative estimate, ranged from eight to 24 inches in diameter. All were attached to intake pumps submerged in the river channel. In several cases, part of the river channel had been excavated with heavy machinery, no doubt, behind small rock wall dams to allow more water to collect at the pump intakes. We also found a handful of artificial channels that led straight to growers’ pumps. Two of the pumps’ generators were running in the afternoon.

Section 1600 of the California Fish and Game Code requires a permit for “excavating material from channels to install and submerge a pump intake,” according to a 2010 Fish and Game memo. Department of Fish and Wildlife environmental scientist Wesley Stokes, who manages stream alteration permits on the upper Russian River, did not respond to requests for information about whether the growers’ dams and channels are permitted. According to Chris Carr of the State Water Board’s Division of Water Rights, these dams “do not fit the jurisdictional requirements of the California State Water Code.”

Most, if not all, of the pumps appear to conform with the legal requirements of the state’s water-rights system. And that system requires no meters or any special drought provisions for Russian River grape growers, other than those in the four Sonoma County creeks. Along with residents, the water board is now asking growers in those four areas to file monthly reports on their water use.

VOLUNTARY MEASURES

For years, wine-industry leaders have opposed regulation on the grounds that it is burdensome and of questionable value. California agribusiness representatives have consistently maintained that they can manage their properties in an environmentally responsible manner without the need for government oversight. In the case of the wine industry, the leading edge of this effort is a marketing and certification initiative called “fish-friendly farming,” which has certified 100,000 acres of vineyards, including a majority of those that suckle at the banks of the Russian River.

The initiative was developed by the California Land Stewardship Institute (CLSI), a nonprofit organization based in Guerneville. “I’m not a big fan of regulations,” says the group’s founder and executive director, Laurel Marcus.

“I think they lead to a lot of conflict.”

Marcus notes that grape growers are undertaking numerous efforts to increase water efficiency, such as construction of off-stream storage reservoirs in the upper Russian River, which they can fill during high-flows in the wintertime and thereby reduce demand during the frost-protection season and in the summertime, as well as soil-moisture meters to help minimize use of irrigation water.

Industry giant Kendall-Jackson has donated money to the “Flow for Fish” rebate program to provide free water tanks to individuals in the four watersheds who agree to conserve water voluntarily. The program is overseen by Trout Unlimited, and several property owners have signed up so far.

A review of the CLSI’s Form 900s filed with the IRS reveals that

eight of the organization’s nine board members are grape growers. The lone exception is Marcus. The organization’s president is Keith Horn, the North Coast vineyard manager of the world’s largest wine corporation by revenue, Constellation Brands.

Tito Sasaki, chairman of the Sonoma County Farm Bureau’s water committee, says his organization is “against meaningless regulations imposed upon us” and notes that some farmers have agreed to release water voluntarily. In a letter to the water board earlier this year, he wrote, “[R]egulations put a wedge between the regulator and the regulated” and “at times become a hindrance to practical solutions such as the aforementioned release of privately held irrigation water.”

Kimberly Burr, an environmental attorney based in Forestville, takes the opposite view.

“If the wine industry really wants to be sustainable, it needs to invite regulation,” she says. “And I believe there are some in the industry who truly want healthy, thriving rivers and will come out in favor of regulation.”

THE NO. 1 THREAT

The lynchpin of state and federal agencies’ effort to recover Russian River coho salmon populations is a hatchery breeding and monitoring program that began in 2001, after the river’s coho population had plummeted to fewer than 10 returning spawners. The program has cost taxpayers more than $10 million so far and has led to a slight rebound in the river’s overall population of fish, which UC Cooperative Extension coho monitoring coordinator Mariska Obedzinski says is in danger of unraveling in the drought.

Fishery officials have been compelled to assess the wine industry’s impacts on occasion. At a November 2009 workshop, a National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) biologist presented data showing that, of 60,640 acres of vineyards in the Russian River watershed, an estimated 70 percent come within 300 feet of salmon-bearing streams. In its 2013 Russian River coho salmon recovery plan, NMFS lists agriculture—meaning vineyards, mostly—as the fish’s

No. 1 threat.

As Alan Levine of the environmental advocacy organization Coast Action Group notes, California State Water Code 1243 orders that the Department of Fish and Wildlife “shall recommend the amounts of water, if any, required for the preservation and enhancement of fish and wildlife resources.”

“Exercising regulatory authorities to protect fish is very unpopular with agriculture,” says Levine.

Many observers of regional water politics lay much of the blame for a regional lack of watershed protection at the feet of Sonoma County. As a 2011 Bohemian story, “The Wrath of Grapes” noted, the county has elected not to conduct environmental reviews of vineyard well permits. And, as the article also noted, the county’s planning supervisor could not recall a single case where the county had rejected a winery application.

[page]

When the state was preparing to institute its new emergency regulations on the river, county supervisors Gore, Efren Carrillo and Susan Gorin traveled to Sacramento and met with state officials, including California Secretary of Food and Agriculture Karen Ross (who was a chair of the California Association of Winegrape Growers for 13 years), Department of Fish and Wildlife chair Charles Bonham and water board representatives. According to Gore, the emergency regulations offer a chance for rural residential property owners and the wine industry to work together toward a common goal over the long-term.

“We need to do everything we can do to get water into those streams this year for coho, and then we can have a full-court press when it comes to increasing long-term storage and permanently reducing water use in those areas,” Gore says. “For that to happen, everybody—and this includes grape growers—needs to step up.” One thing the county is talking about, he says, is targeting marijuana eradication operations in the four watersheds.

A common complaint among environmentalists and other residents is that the county has failed to safeguard limited water supplies by approving all new well construction and vineyards under its jurisdiction, including in the four critical areas for salmon, on a “ministerial” basis instead of requiring environmental review, such as a scientific assessment of the development’s impact on endangered species habitat. And, while there are an estimated 800 illegal diversions of waterways in the Russian River watershed, according to water board documents from 2010, the county does not require that developers demonstrate they have a legal water right.

Gore says that the county’s “ministerial” well-permitting will remain in place and cited a new well ordinance requiring that wells be installed at least 30 feet from streams as an example of progress toward a stricter groundwater policy.

A HIGH PRIORITY

Few California waterways are historically as important to coho and steelhead as Mark West Creek, one of the four creeks subject to the water board emergency regulation. Veteran fisheries ecologist Stacey Li, formerly with NMFS, says he had “never seen abundances of steelhead that high anywhere else in California” when he worked there in the 1970s and 1980s. The Brown administration’s California Water Action Plan acknowledges the creek’s historical role, having named it one of California’s five highest priority waterways for restoration funding.

Vineyard development in the headwaters started in the late 1990s when the owner of a multimillion-dollar dentistry consulting business in Marin County, called Pride, bulldozed about 80 acres of ridge-top oak woodlands to plant grapes (some of which were not in the Mark West watershed). Next to plant a high-elevation vineyard was Fred Fisher, a General Motors scion. But the coup de grace occurred when Henry Cornell, a hedge fund manager whose investment portfolio includes the world’s largest corporate distributor of pipes and valves to the oil industry, purchased 120 acres and clear-cut much of its forestland to make way for a vineyard.

The removal of anchoring vegetation activated a landslide on Cornell’s property, which caused 10,000 cubic yards of soil to wash into the creek during a 2006 winter storm. The stream’s staircasing pattern of slow deep pools, separated by abrupt but short waterfalls, had been ideal for fish. The landslide filled in many of the spawning pools and turned much of the staircase stream structure into a rapid water chute.

The threat of hillside and mountaintop vineyards, which became an industry craze in the 1990s, was already well-known. The trend was driven by companies like Jackson Family Wines (owners of Kendall-Jackson), which touts the superior quality of mountain-grown grapes in its marketing. The resulting bulldozing of hillside oak groves and grasslands has caused enormous amounts of erosion to wash into streams. The vineyard operators have also dammed or diverted numerous streams and drilled deep wells, equivalent to placing plugs and straws in the very mountain veins that had served as the fish’s remaining refuges.

In 1999, UC Cooperative Extension specialist Adina Merenlender undertook the only concerted effort to quantify hillside vineyard growth. She found that 1,631 acres of dense hardwood forest, 7,229 acres of oak grassland savanna, 278 acres of conifers and 367 acres of shrub land in Sonoma County succumbed to wine-grape plantings from 1990 to 1997 alone—42 percent in elevations higher than 328 feet. While no similar studies have been conducted since, Sonoma County vineyard acreage grew from 40,001 acres in 1997 to 64,073.2 in 2013, according to the Sonoma County Agriculture Department, with most of that expansion occurring in the Russian River watershed.

Kendall-Jackson’s Santa Rosa corporate office did not respond to requests for comment.

A PUBLIC TRUST

For years, Laura Waldbaum and other Mark West Creek residents tried in vain to compel fisheries agencies to intervene in the creek’s plight. In Waldbaum’s words, they received the “same cut-and-paste answer every time”: the county, rather than the state, is the “lead agency” on land-use decisions. Therefore, the state is not in a position to intervene. Moreover, the Department of Fish and Wildlife claimed that the vineyards, because they rely on well water, are not subject to regulatory action.

Mark West Creek residents eventually succeeded in convincing NMFS to do one thing: install several low flow gauges in the creek to help quantify the effects of various water uses.

The meters provided data for a November 2014 study by the environmental consulting company Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration (CEMAR). It is one of two official studies on water use in the creeks subject to the water board regulation. It notes that approximately one in eight Mark West Creek residences “have a lawn, visible garden, or other irrigated landscaping.” Although the area CEMAR’s biologists selected for study only contains three vineyards, these properties’ annual water demand is more than two-thirds of the area’s 222 residential properties.

As fisheries officials noted at each of the Russian River emergency regulation meetings last month, however, young coho salmon and steelhead trout are most vulnerable in the summertime, when streams are not being replenished with rain. And that’s exactly when the grape growers now pumping at the banks of these fish’s rearing habitat need water for irrigation. The wine industry uses a similar share of the summertime water in Green Valley Creek, according to a separate CEMAR study.

Now that so much damage has already taken place, Waldbaum and other residents view the state’s relatively sudden interest in Mark West Creek water use as part tragedy, part irony.

“This is ground zero for the state,” Supervisor Gore says. “If the drought continues, everyone else in California will be looking at the same type of regulation. So the state is looking at this area to see if we can achieve success.”

The measure of that success is not only whether coho salmon and steelhead trout survive, environmentalists and policy analysts note, but whether they start to recover. California’s Supreme Court has upheld the primacy of the “public trust doctrine,” which obligates state government to protect public-trust resources, our common heritage of water, rivers, animals and plants, and their interrelationships, whenever feasible. The doctrine is supposed to underlie all efforts undertaken by regulatory agencies to protect the state’s waters. It provides that no one has a right to appropriate water in a manner harmful to the interests protected by the public trust, including fish.

“Salmon bring their biomass back to our rivers from the oceans every year, for free,” notes California water policy expert Tim Stroshane, a policy analyst for Restore the Delta in the Bay Area. “What a miracle. That’s what protecting the public trust is for. That amazing natural subsidy is why it’s the duty of the state to protect them.”

An increasing number of Sonoma County residents are deciding that neither the state nor the county are upholding that duty.