Art History

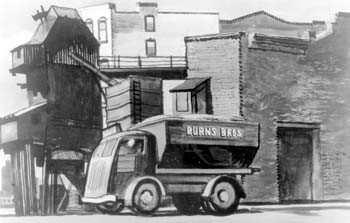

Golden State: The work of painter Millard Sheets, such as “Burns Bros., 1936,” above, documents California as it was.

“California Scenes” exhibit paints the state

By Gretchen Giles

SURELY THERE ARE MANY of us left who remember those times, in the 1930s and ’40s, when California was still an unmolested land of yellow hills, green oaks, and golden promise. The Depression was bending the nation at the knees, but California remained relatively untested, booming still with land developers, timber harvesters, farmers, speculators, filmmakers, and the tidal bounties of the ocean.

That time is not lost for those with memories or life too short to recall it, captured yet in the paintings of the era. “California Scenes,” an exhibit of some of these works opening Aug. 21 at the Sebastopol Center for the Arts, evokes that decade before the Second World War when young painters such as Millard Sheets armed themselves simply with a set of watercolors and an eye for the land.

Curated by Sheets’ son David Stary-Sheets, a Laguna Beach gallery owner who formerly had a gallery in Gualala, “California Scenes” features the work of Sheets and 26 contemporaries. After leaving Sebastopol, the exhibit will travel to the Orange County Museum of Art and the Ventura Museum of History and Art, not dismantling back into the collectors’ homes from which it was culled until early next summer.

“I think that the important thing from the standpoint of a show like this is that [the artists] are portraying a period of time in history. They are a commentary on that time, and in relationship to that time. It was two of the roughest decades that this country’s ever been through,” says Stary-Sheets by phone from his Southern California gallery.

“They portrayed it in the sense of how they lived it, and luckily for Californians, it wasn’t so bad as the rest of the country, so there’s an optimistic quality to the works.

“Art is as important in describing historical events as all of the articles in all of the papers of all time,” he continues. “For centuries, art was the communicative force, and now it’s TV and radio and newspapers, which I think are very important, but we’ve lost the sense of the importance of communication through the arts.”

Communicating is paramount to the works shown in “California Scenes.”

“They were early American impressionists,” Stary-Sheets says of the artists. “They were painters who were painting real life, and what was happening in city streets and the construction of buildings and those kinds of views were much more interesting to this young group of artists.

“Now, it wasn’t just in California where the idea of the American scene was being recorded,” says Stary-Sheets, who is an expert on this era. “It was a national movement. It just happened that in California there was this absolute fascination with watercolors.”

Long considered useful for sketching, for containing quick ideas, and for grading out color concepts, watercolors are often the sneered-at sister of the painting media. For Sheets and his contemporaries, they were pure magic.

According to Stary-Sheets, the work of his father–who was also a renowned architect, known for his murals and for the brilliance found in his designs for over 40 Home Savings and Loans buildings statewide–“brought watercolor to national recognition as a finished form of art. When I say that, I’m not ignoring the fact that [painter] Winslow Homer had done that almost a century before, but he was an individual who only served himself and his art; he didn’t cause watercolor to be accepted nationally.

“Millard and his contemporaries brought watercolor to the masses,” says Stary-Sheets, who refers to his father formally in conversation as ‘Millard Sheets.’

More masses may become familiar with these watercolors if a plan to house a permanent collection of Sheets’ work is successful. A donor stands poised to bestow some 55 of the painter’s works on the center if matching funds to build a separate housing for them can be raised. Inspired in part by Tony Sheets, Millard’s Sebastopol-based son, and an artist who sits on the center’s board, this endowment could prove very significant to the center and to the county as a whole.

IRONICALLY, Sheets is best known for his oil paintings, in which medium he painted a yearly exhibit; the watercolors generally languish in drawers. “His watercolors are in every museum in the country; you just never get to see them,” says Stary-Sheets shortly.

Not slid away, however, are his wartime works, paintings done in Burma depicting the brutality of the war and the terrific injustices of life, such as children starving outside of restaurants while rich people dined richly. They are on permanent display at the Department of Defense in Washington, D.C.

“It’s probably going to be recognized as one of his most important contributions,” says Stary-Sheets, “but it’s very tough stuff. And the pictures that I’ve picked for the exhibit in Sebastopol are not the starvation pictures. I want people to come in and enjoy the show and gain knowledge, but not turn people’s stomachs.”

Millard Sheets lived for almost 82 years, not an inconsiderable time. “He had a heckuva a life,” says his son. “I wish that he was still here, but he was pretty well satisfied that he had met the challenge.”

And like his life, his work lives on. “Properly cared for, just like any work of art, watercolor is as durable as time. After all,” says Stary-Sheets, referring to tomb and cave paintings, “the oldest paintings known to man are watercolors.”

“California Scenes” shows Aug. 21 through Sept. 28 at the Sebastopol Center for the Arts. A public reception is planned for Thursday, Aug. 21, from 6 to 7:30 p.m. Tony Sheets gives a special presentation on Thursday, Sept. 4, at 7 p.m. 6821 Laguna Park Way. 829-4797.

From the August 14-20, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.