The state housing department is gearing up to send stern warnings to cities trying to skirt a new housing law advocates hope will bring more affordable housing.

Senate Bill 9, a state law that went into effect Jan. 1, allows property owners to build duplexes and in some cases, fourplexes, on most single-family parcels across the state. Cities, more than 240 of which opposed the bill, have pushed back against the state with ordinances that would severely curb what property owners can build.

The Housing and Community Development Department confirmed it has received complaints about 29 such cities it told CalMatters it plans to investigate. If it determines cities are indeed defying state housing laws, the department will send letters that offer technical assistance, and request a plan to fix those issues within 30 days.

The first of those letters will be sent out “relatively soon,” according to David Zisser, who leads the housing department’s newly created Housing Accountability Unit. Zisser said he hopes the department won’t have to issue letters to all the cities they investigate.

“By the time we send out a few letters, my hope is that jurisdictions will start to see themselves in those letters and start to make corrections to their own ordinances,” he said.

If a second warning letter fails, the state attorney general’s office, with whom they have been coordinating closely, would step in.

In fact, Attorney General Rob Bonta has intervened twice already. Pasadena carved out exemptions for landmark districts within the new law, which could apply to vast swaths of the city. Bonta told the city last month they could face a lawsuit if they didn’t reverse course. In a response letter, the city’s mayor said they are in full compliance with the law.

In February, Bonta also called out Woodside, a wealthy Silicon Valley town that claimed its entirety was protected mountain lion habitat and therefore couldn’t accommodate duplexes. It quickly reversed course following the state’s warning.

Both cities were on the housing department’s list of 29 cities.

The state housing department doesn’t have authority to enforce the duplex law, according to Zisser, which is why the cities on their list will be investigated for defying the 16 housing statutes under their purview, one of which limits a city’s ability to restrict the development of new housing.

Who’s on the naughty list?

Temple City, a Los Angeles suburb of 36,000 with a median home value of nearly $1 million, crafted an ordinance in December—ahead of the law going into effect—with a list of more than 30 development and design standards property owners must meet in order to develop new homes under the state’s new duplex-friendly law. The purpose of the ordinance was not a secret.

“What we’re trying to do here is to mitigate the impact of what we believe is a ridiculous state law,” said councilmember Tom Chavez during a Dec. 21 city council meeting, in which they unanimously adopted an urgency ordinance limiting the effect of the duplex law in the city. He acknowledged the state may push back.

Traditional single-family zoning—with room for one house for a single family with a front yard and a backyard—is what has always attracted people to Temple City, said William Man, another councilmember.

“SB 9, at least in principle, is dismantling that before our eyes,” he said.

Temple’s ordinance says property owners must get rid of their garage or driveway before getting a building permit, and residents of the new unit will be banned from obtaining street parking passes. New tenants can’t own a vehicle and must intend to walk, bike or take ubers around the suburb, according to a planning memo.

The city is also demanding that all new units meet the highest level of LEED certification, a designation typically held by premium office buildings like Facebook’s Headquarters in Menlo Park.

Finally, the new ordinance says new homes can be no larger than 800 square feet—also the minimum set by state law—and must be rented at below-market value to be affordable to low-income families for 30 years, a standard that is echoed across multiple cities’ anti-duplex law ordinances. A family of four would need to make $94,600 or less to qualify, and could only be charged 30% of their total income in rent, or $2,365 a month.

The affordability requirement threatens the viability of these projects, according to Muhammad Alameldin, a policy associate at UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation who has been reviewing multiple ordinances for an upcoming analysis.

While developers who build affordable housing usually rely on subsidies from the federal and state governments to operate, “These are just homeowners who have no assistance from their localities or from anyone, and lack technical expertise,” he said.

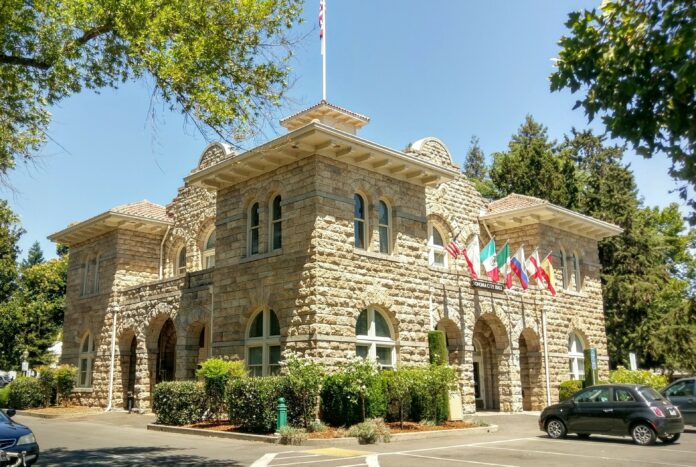

Another city on the housing department’s list: Sonoma, a historic city north of San Francisco known for its ritzy wineries. Besides requiring similar affordability covenants for new housing, Sonoma now requires that any prospective duplex property have at least three mature trees and 10 shrubs. The new duplex unit or singular house would have a maximum area of 800 square feet, and at least 600 square feet of shared yard space.

The count of cities with restrictive ordinances is higher among some pro-housing advocacy organizations, like the California Renters Legal Advocacy and Education Fund. They identified more than 55 cities by following city council and planning department meetings in which “it’s pretty clear the intent is to limit the use of SB 9 as much as possible,” said the group’s executive director Dylan Casey.

The typical median income across the 55 cities was $129,000, while the average home cost $1.9 million.

“With few exceptions, these are mostly the very expensive, very high- income suburbs that are rushing to prevent implementation of SB 9,” Casey said.

A few other cities have engineered creative strategies to work around the law without catching heat from the state yet.

Absent from the state’s watch list is Laguna Beach, a surf town in Orange County, which is playing with geometry to ensure property owners don’t split their lots, according to Isaac Schneider, co-founder of Homestead, a startup that helps homeowners develop Accessory Dwelling Units and more recently, split their lots under the new duplex law.

Schneider said the law’s power lies in lot splits, whereby property owners can cut their land in half to create smaller, more affordable parcels and thus spur homeownership. Laguna Beach’s ordinance says the owner can’t do that, unless the new lot is a perfect rectangle.

That presents an issue, Schneider explained, because the line for most lots would need to be drawn behind an existing house—in the backyard. But in order to have street access, as required by law, planners normally create a flag shape, with a driveway or other access point to reach the new house without demolishing the existing structure. (Sonoma’s ordinance also bans flag lots.)

The ordinance also requires the new lot to border the road for at least 30 consecutive feet. However, the typical lot is 50 feet wide in Laguna Beach, Schneider’s group found. That means if a house is situated in the center of the lot, a lot split would require demolishing the existing home.

“They’ve made a math problem you cannot solve,” Schneider said.

When CalMatters asked if these restrictions would render most projects infeasible, Laguna Beach Community Development Director Marc Wiener wrote in an email: “The intent is that subdivided lots have standard property boundaries and that there is adequate vehicle access to both parcels. Most lots are rectangular and meet the 30-foot frontage requirement, therefore it is not viewed as a limiting factor.”

While the duplex law was a nail-biter in the Legislature, and continues to incite resistance among cities, it has barely made a dent in housing production. Planners in Bay Area cities haven’t heard a peep from property owners looking to split their parcels or build a duplex.

Sen. Scott Wiener, a Democrat from San Francisco, says the law has only been in effect for 90 days, and resistance from cities is just a feature of housing legislation in the state.

“It’s not surprising at all that there will be resistance and cities will try to find loopholes,” he said. “We just need to enforce the law, and we now have the attorney general and (the housing department) willing to do that plus private litigants who will sue if need be. And if it turns out that there are loopholes that need to be closed, we can do that.”

But cities are also reverting to legal challenges. A group of four LA County cities, led by wealthy Redondo Beach, filed a lawsuit March 29 in Los Angeles County Superior Court against the attorney general’s office, claiming the state “eviscerated” cities’ land use control.

Bonta’s office issued a statement in response: “We look forward to defending this important law in court and we will not be deterred from our ongoing efforts to enforce SB 9 and other state housing laws.

This article first appeared in CalMatters.