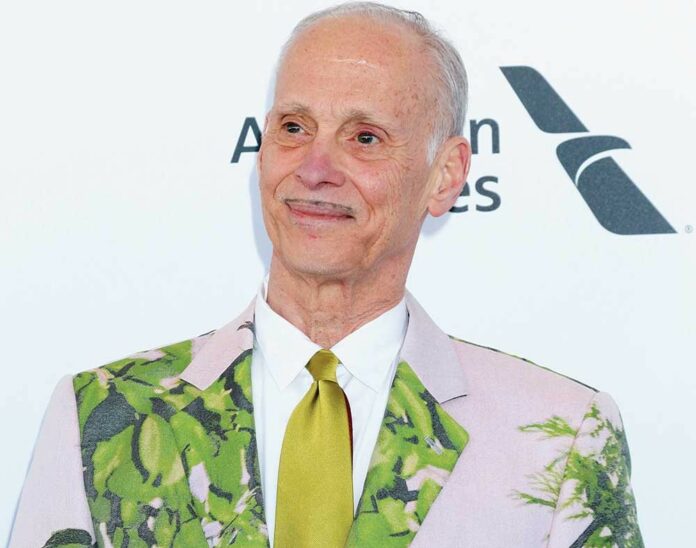

“Somehow I became respectable. I don’t know how,” writes John Waters in the opening lines of his new book Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder.

But the rest of us do. The world might have been scandalized by the sight of a 300-pound drag queen eating dog droppings in 1972’s Pink Flamingos—the only movie in exploitation history to have a tagline that actually undersold its excesses: “An exercise in poor taste.” But almost a half-century later, Pink Flamingos now plays unedited on cable, not to mention the fact that it’s one of most beloved cult films of all time. And Divine, the outrageous drag queen at the center of the Dreamland troupe of actors and associates who appeared in Waters’ early films—including the “Trash Trilogy” of Pink Flamingos, 1974’s Female Trouble and 1977’s Desperate Living—now adorns everything from shirts to votive candles to coronavirus-resisting face masks on Etsy.

Waters, meanwhile, is now the unofficial Dirty Grandpa of several generations of misfits. He’s been to Hollywood and back, and won over audiences in both arthouses and multiplexes. Hell, you could even take your mom to the Tony-award-winning Broadway version of Hairspray.

But when it comes to the question of how he became respectable, the answer is simple: He stepped out from behind the shock tactics and movie gimmicks (although, let’s be honest, the “Odorama” scratch-and-sniff cards for 1981’s Polyester—featuring scents like gasoline, dirty shoes, new car smell and farts—were genius). He started getting real all the way back in the ’80s with his book Shock Value, and he hasn’t stopped. His crazy early films were always comedies at heart, but the humor he revealed in his writing was warmer and more relatable, and he connected with his growing legion of fans in an entirely different way. That appeal has only expanded over the years through his subsequent books, live shows and holiday-themed music compilations. There’s even a John Waters summer camp now.

In Mr. Know-It-All, he connects all of his various cultural obsessions, sharing stories and offering advice on everything from filmmaking to fine art to food to political activism—and, of course, sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll. I spoke to Waters about his new book, and why respectability didn’t ruin his career.

I just finished ‘Mr. Know-It-All’ last night. I want to do a spoiler where I tell everyone ‘He dies at the end.’

JOHN WATERS: Yeah, you could do that, that’s definitely true. But I die and then tell you how to beat dying.

One critic called you ‘an indefatigable coiner of droll one-liners,’ and that’s as true as ever in the new book. It’s not really just one-liners though. You’ve expanded into two-liners and three-liners.

I could spend my entire life speaking in blurbs, in sound bites. I think that’s from enjoying the media and always reading how journalism takes something and makes it appealing to everybody. There was a headline in the New York Post the other day when Dr. Fauci threw out the first ball at the baseball game: “Catch This.” It was so funny. That’s the kind of thing that, I don’t know, you need media training. I mean, I start my day with about eight newspapers.

Has anyone ever actually called you Mr. Know-It-All?

Nobody ever called me that—well, I think it was always used in a negative way. People would say, “Well, Mr. Know-It-All! You think you know everything!” And I’ve kind of made a career of embracing negative images. I don’t know, I just liked the title. I always come up with titles. Every one of my movies, I had to have the title first. Since I was going to cover every subject and tell every anecdote I had in my anecdote bank, I thought it would be, in a way, passing on advice to young people about what I’ve learned about negotiation through 50 years. And I think it is a self-help book, for real, even though it’s a humorous book. Hopefully.

The first 100 pages or so is devoted to filmmaking. You write, ‘Winking at the audience was not necessary if you believed, as I did, that the lines were funny enough on their own.’ I love that, because your movies are often described as ‘campy,’ but I think of Steven Dorff in ‘Cecil B. Demented’ and how he’s playing the opposite of camp—with total conviction. And that’s why it works.

He doesn’t do that once—he never winks at the audience. That’s my first direction with everybody in every movie: “Say the lines as if you completely believe them to be the most serious lines.” And that is why I usually hate movies that the critics say are very “John Waters-esque.” Usually they’re in purposeful bad taste, being blatantly obvious about it, and trying to be campy. I like the idea of saying it as if you believe every word of it, and I think all my movies have had that. Even the most ridiculous dialogue, like in Female Trouble where Divine says, “I’m going to go upstairs and sink into a long, hot beauty bath, and erase the stink of a five-year marriage.” I mean, that is the most ludicrous soap opera line. But Divine said it as if she believed it. I think that’s important to the humor.

How much did Divine influence your view of gender fluidity?

Well, Divine had no desire to be a woman at all. He was not trans in any way. He was a drag queen and an actor. In the old days, when I first saw the Jewel Box Revue [a company of female impersonators which toured for decades, beginning in the late 1930s], you had to go see it in African American theaters, even though white people went. That was the first drag show I ever saw; it was a professional drag show that toured. Diane Arbus took a lot of pictures of that. It was all men playing women, except the lead was a woman playing a man—a drag king, which was even kind of more radical then. Milton Berle fucked with it; he was the most watched person on television, and he was in drag. But then Divine fucked with it, because he was overweight. They all tried to be beauty queens and Miss America—Divine would have burned down Miss America’s house! Divine was a monster and a drag queen. And Divine got his best reviews when he put aside that image he first got famous for and played a loving mother, a normal person, because he was going so much against this type we had made up for him.

Your memories of ‘Hairspray’ are very sweet, and it’s funny that the name of that chapter is ‘Accidentally Commercial,’ and then the following ones are ‘Going Hollywood,’ ‘Clawing My Way Higher’ and then ‘Tepid Applause,’ ‘Sliding Back Down’ and ‘Back in the Gutter.’

I failed upwards a lot. I don’t know if that’s as possible to do today. But it is, in a way. Something has to have been successful recently that it reminds [studio executives] of, even if it’s not yours. You can pitch it in a certain way, although every pitch I ever gave about my films being commercial, I meant it. I was never lying. I believed that every one of them could make money. And weirdly enough, eventually they all will. Because they won’t go away.

Was there a particular moment where you felt like, ‘Finally, the weirdos won!’?

Yes, I think three times in my entire career. Once, when Pink Flamingos had been out, and I had been showing it myself in different cities and saw that it worked—but it had never played New York. New York was the very last place it played. Finally, New Line picked it up, and we showed it one week at the Elgin, and maybe 50 people came. They said, “Okay, you can have one more week,” and I went back the next week and the line was around the block from word of mouth. That was one night my career changed. Another night was when Hairspray won the Tony. I mean, that was definitely career-changing. And the first time one of my later books made the bestseller list. Not because that says it’s good or bad, but it was something I never thought possible.

How did mainstream culture come to accept the Pope of Trash? Do you think you changed, culture changed, or both?

I didn’t change that much, but I kept up with the times and always knew the audience was changing—and coming my way. I realized that people wanted me to scare them, but not in a negative way. I loved everything I made fun of, always. I think that’s why I lasted. I mean, I can be mean-spirited, but if I ever am, it’s about Forrest Gump. Who cares that I don’t like Forrest Gump? Even Tom Hanks doesn’t. The movie won every Oscar and made a billion dollars. I never say negative things about people too much, except Donald Trump. And even when I make fun of him … no, I’m mean about him. I don’t feel guilty about that. Because he won’t last. That’s why I would never put him in anything I write or anything. He’s not mentioned in the book, because that dates it. You immediately date yourself if you put something in like that.

Speaking of being caught up in the moment, was it hard to write your commencement speech to the graduating class of the School for Visual Arts in May?

Well, I had to write it in the middle of the virus—it was supposed to be 5,000 people in Radio City Music Hall, but of course I had to do it virtually. Now, I must admit I’m a little lucky because it happened right before the racial uprising, which would have been even harder—as a white man—to ever cover that with humor in any way. I think that anybody that has any speaking engagement, everything has to be completely rewritten now. Because you can’t just ignore what’s going on now. It’s a completely different time. I did say in that speech, “You kids, if it ever goes back to the old way of ‘normal,’ it’s your fault.” I didn’t mean to be prophetic, but they didn’t go back to the old normal. They certainly thought up the new normal in protesting, and how great that it’s gone this far. And how sad that I’m old! I don’t want to get the virus!

I love that the only reason I have to ask whether this is actually true is because you’re John Waters and it just might be, but that part in the book about you and your staff licking every parcel you send out to studios—is that a joke?

No! I have pictures of them doing it. In the old days—well, when I finish something I still don’t submit it totally online. If I had a new script, I would send them a bound copy with a cover and everything, right? As we put it in that FedEx, as we turn in the final thing—like when I send in a book for the first time—everyone who works for me knows they have to wet the package before they put it in the mailbox.

What the hell? How did that even start?

I don’t know! It was just for good luck. It’s a little ritual. I have a picture somewhere—I’m not going to give it to you—of the staff all licking the same envelope out in front of my house. These days, I guess that’s not too safe. I hadn’t better be saying that, or FedEx won’t come to my house for pickup! I guess I’d have to put that on hold if we were doing it today. Then I wouldn’t get the deal, though.

John Waters speaks in conversation with Steve Palopoli for a virtual event presented by Bookshop Santa Cruz on Wednesday, Aug. 12. 7pm. $24; includes a shipped copy of ‘Mr. Know-It-All.’ bookshopsantacruz.com.