Since #MeToo burst onto the stage this past fall, sexual violence against women has finally achieved the public recognition long overdue a crippling problem, one that has plagued women and girls for decades—maybe centuries. And it’s not going away.

But perpetrators are beginning to be held accountable. In May, Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein turned himself into police in New York for sex crimes. Bill Cosby, similarly accused of molesting dozens of women, faces 30 years in prison after his conviction. Still, the National Crime Victimization Survey shows that 99 percent of perpetrators walk free.

“The more high-profile these situations are, the more people will have to open their eyes and ask why this is happening,” says Yesenia Gorbea of Futures Without Violence in San Francisco. “Survivors are able to step forward because they feel they can be heard. It’s a cultural shift we’re seeing. Finally, issues are being talked about, informed by the survivors themselves.”

“#MeToo is fantastic, a huge breakthrough,” says Jan Blalock, chair of the Sonoma County Commission on the Status of Women. “It does bring to light what has been going on. But are people safer? No, but it’s safer to talk about things.

“We’re in a very dangerous time,” Blalock continues, “with the internet and easy access to pornography—especially for boys who think this is normal or what girls want. You can order a child to have sex with as easily as ordering a pizza.” But even more dangerous are the trafficking networks that use social media

to trap young girls into forced

sex work.

Sexual abuse is about power, says Caitlin Quinn, communications coordinator at Verity (formerly Women Against Rape), a social service nonprofit in Santa Rosa. “Abusers prey upon people that they perceive as weak in some form or another, with more marginalized identities or with disabilities,” Quinn says. According to a yearlong study by National Public Radio, people with mental or physical disabilities are five to six times more likely to be abused. “It’s an epidemic no one talks about.”

The National Sexual Violence Resource Center reports that one in four girls will experience sexual violence before the age of 18. If it’s about power, will empowering girls help keep them safe?

G3: Gather, Grow and Go is a Sonoma-based nonprofit for women that “creates experiences to help you leverage your best.” It offers programs for teen girls, and recently has developed programs for mothers with their daughters. The group holds daylong and weekend workshops aimed at “empowering girls to leave with a heightened awareness of who they are and who they want to become,” says co-founder Michelle Dale.

But Dale is clear that G3’s programs, which pre-date #MeToo, have not been adapted in response to that movement.

Dale is a bright, beaming single mother of two teen girls. She says the workshops take a holistic approach “to reignite the magic inside us that sometimes grows dim,” and encourage wellness to support self-confidence, as well as recognizing “the power of no.”

“We believe the work changes how people look at themselves,” she says.

Workshops for teens are designed to address the many challenges girls face. “First and foremost is technology and social media,” says Dale. “It makes girls feel left out, not good enough. Everyone else is doing everything they want to be doing. . . . It also limits your basic face-to-face social skills.”

And it also exposes them to the creeping tentacles of traffickers.

Dale favors limiting a child’s time on social media, and not only for girls. Perhaps most damaging is “the epidemic of young boys thinking it’s OK to play video games eight hours a day, winning the game by killing each other.” What about their social skills, their ability to feel empathy, she asks.

G3 workshops provide “opportunities for girls to feel empowered to stand up and give voice to what they will accept or not.” But they do not address the issue of sexual assault directly. “We build voice and confidence and sisterhood, and those things work to allow women and girls the courage and support to live strong, live brave and speak their truth and help others to do the same,” Dale writes in an email.

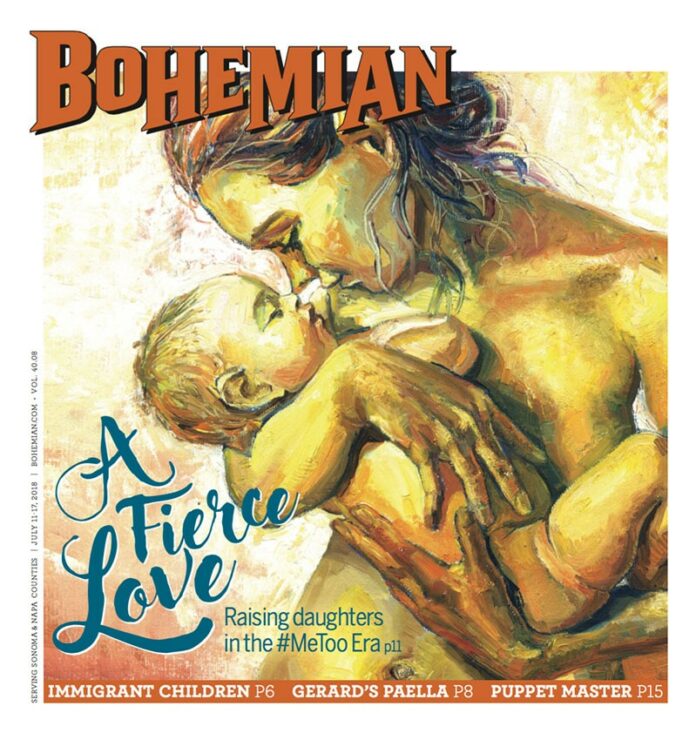

Bringing mothers and daughters together for quality time is key. “It allows everybody to slow down to find the connection that brings them closer together.

“Your relationship with your mother is very important, maybe the most important one you have.”

Quinn seconds that. “Mothers need to do everything they can to talk to their daughters. Sometimes that means being vulnerable. A lot of mothers don’t want to share what violence has happened to them, but that can help a daughter understand her point of view. Lots of women are still blaming themselves for what happened to them.”

But for Dmitra Smith, vice chair of the Sonoma County Commission on Human Rights, it’s not possible to look at this issue without considering intersectionality, the interplay of race, class and gender.

[page]

“What if Mom is a single mom working several jobs to make ends meet? She may not have time to talk to her daughter,” Smith says.

“If you look at the #MeToo movement, that term was coined over 10 years ago by Tarana Burke, a black woman who was largely ignored. For me, as a woman of color, it’s great that so many women are finding their voice, but there’s a sense of frustration at how it took a segment of mostly white women who are affluent to talk about it for it to be receiving the attention that it deserves.”

Reports vary, but generally white women and Latinas experience more assault than black women, while Native American women endure the most abuse; and assault by a white man is the most common.

“I’m still reminded that women of color, indigenous, undocumented and poor women are systematically sexually and physically abused by law enforcement and incarceration systems who then evaluate themselves and find nothing wrong with their actions,” said Smith.

Worsening the problem for all women, social media has made the world more dangerous than ever, especially for young women, and it is one of the hardest to combat. “As soon as the police or our advocates have figured out one new lure or app,” says Quinn, “these guys come up with another one.”

One example is Snapchat, “an app that teens love to use,” Quinn says. Users can have their location “turned on,” allowing friends and contacts to see where they are. Kids need to know that setting it “public” is risking trouble, Quinn says.

Social media has enabled traffickers to make easy contact with vulnerable girls. And once they target a young girl—promising her a fabulous career as a model—it may be hard for her to resist.

Even harder is for a girl once trafficked to get out. Tiburon’s Shynie Lu, a recent graduate of Sonoma Academy, made a video as a project for the Sonoma County Junior Commission on Human Rights, called Strong Survival. In it, she interviews Maya Babow, who managed to escape from her traffickers after six years.

“People ask, why didn’t she leave sooner?” says Lu, “But when you hear her talk about the threats they made, how they would hurt her family, and about withholding food and water from her, she made it clear why she wasn’t able to walk out.” Now an ambassador for Shared Hope International in Marin, Lu helps inform high school students about the danger.

So once #MeToo drops off the radar, will perpetrators again find refuge in the surrounding silence?

Rates of sexual violence are declining, and continued outcry will certainly help, but empowering girls may not be enough to create the kind of change women rightfully demand. “I was a highly empowered teen,” says Blalock, “an athlete, but I was raped.”

Maybe change has to happen on the other end of the spectrum. As Babow says in the film, “We need to stop the demand. If you can stop the demand, there is no need for supply.”

Futures Without Violence has started a nationwide program called Coaching Boys into Men, in which male athletic coaches are trained to lead workshops for their teams to deliver the message that is is manly to respect girls. But there do not seem to be many such programs currently in place in local schools.

“The onus is on society to see girls and women as equal, intelligent beings worthy of respect rather than objectifying them,” said Blalock.

Instead of teaching girls not to get raped, we can teach boys not to rape—soon.