How Jerry Got His Soul Back

Four years after their viciously fought battle in the 1992 Democratic presidential primary, Bill Clinton is in the White House while Jerry Brown lives in a west Oakland warehouse-turned-left activist lair. But guess who’s the happier man?

By Zack Stentz

“LET JERRY SPEAK.” OK, so it doesn’t rate up there with “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too” or “Fifty-four forty, or fight!” as an immortal phrase in the American political lexicon. But the oft-repeated chant at the 1992 Democratic Convention in New York still serves as a reminder of the formidable power wielded at one point in that year’s political cycle by none other than California’s own, er, interesting former governor, Jerry Brown.

Running a shoestring campaign on maximum $100 donations, sleeping in supporters’ guest bedrooms, and throwing well-aimed rhetorical grenades at rival Bill Clinton (at one point calling the then-chief executive of Arkansas a “union-busting, wage-depressing, scab-inviting environmental disaster of a governor”), Brown managed to shape profoundly the parameters of debate during the Democratic primary season, despite his eventual loss. And his once-derided flat-tax plan to radically alter the American income tax code is now a mainstream tenet of the Republican Party amongst the likes of Jack Kemp and Steve Forbes.

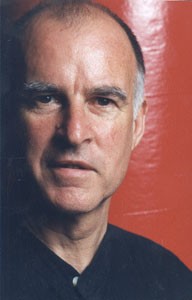

The four years since his last race have been kind to Brown the man. His now-buzzcut silver-and-black hair has receded to near-nonexistence, but the familiar hawklike nose and focused gaze make him a still formidably intense presence, a bit like Captain Picard crossed with your favorite college professor. It’s also clear that his political passions from the 1992 season remain undimmed. Asked whether his 1992 assessment of Clinton still holds after the president’s four years in the White House, Brown replies: “What I said in 1992 remains true today. Clinton is exactly as I perceived him to be.”

But though his former rival may have grabbed the political brass ring of the White House with all the power and responsibility it entails, while Brown is now ensconced in a converted warehouse living the life of an activist college undergrad, which man is leading the more fulfilled life?

Imagining Clinton, a man always more comfortable campaigning than leading, as happily dealing with Whitewater, welfare reform, and Bosnia seems difficult at best. But removed from the centers of power and influence–whether by fate, hubris, or his own design–Jerry Brown seems to be thriving as a born-again populist crusader.

Because of his Jesuit training and sometimes ascetic lifestyle, it’s become a cliché to compare Brown to some sort of monk (St. Francis to his admirers, Rasputin to his detractors). But watching him in his new home, petting a dog and smiling broadly while describing the world’s plight and the state of American politics in the bleakest terms possible, the analogy that comes more readily to mind is to Camus’ Sisyphus, happy and contented as he pushes his stone up an impossible hill for all eternity.

Mocking Clinton’s claim that life in America has improved during his term in office, Brown continues: “For Clinton, things are getting better. He’s making $200,000 a year, and the people spend half a million dollars each time he gets on a plane to give a speech. He’s living in the lap of power and luxury, and so are the members of Congress and their contributors and hangers-on.

“But for a huge number of the American people–whether its 40 or 60 percent isn’t important, it’s a lot of people–their quality of life, their economic security, the prospects for their children are diminishing, and have been diminishing for the last 20 years. That’s a fact. Take, for example, the failure to raise the minimum wage for nearly four years, and then to raise it 90 cents, to ensure that someone who works at the minimum wage of $5.15 an hour stays below the poverty line. That’s intolerable in a society this rich, when the Dow is near 6,000. It’s criminal. And yet, because [Republican presidential candidate Bob] Dole is the captive of the Right, Clinton is able to cozy right up to the Right, and the vast majority of Americans are left with symbolism and deceptive propaganda as the only things they get from their leaders.”

Brown even goes so far as to characterize Clinton’s presidency as being worse for the nation than a second Bush term might have been in its place. “It’s far worse,” he says. “Not even close. Clinton has imposed the most drastic cut in America’s commitment to poor children, since . . . well, we’ve never had it since Roosevelt. Not even Nixon or Reagan attempted to force the needy to fend for themselves, in an economy that, since it’s globalized, will force people into the streets, to huddle over grates to keep warm in the winter. The welfare bill that Clinton signed, in terms of its effect on children, on immigrants, is absolutely reprehensible and a moral blot that will become clearer in the years ahead.

“And No. 2,” Brown adds, banging on a table for emphasis, “the crime bill and the anti-terrorist bill are both aimed at increasing police state powers of surveillance, wiretapping, and numbers of armed bureaucrats wandering about the country. All of that is a centralization of power, and divergent from the Jeffersonian ideal of a more decentralized democracy. Clinton has brought this about. And the adoption on the international level of NAFTA and GATT, with no real protection for the environment or the falling wage standards for so many Americans, is something that I believe a Democratic Congress would have blocked Bush from doing.

“So Clinton has in effect been able to destroy the vestiges of progressive politics and co-opt the global business perspective at the cost of American social stability and justice.”

Brown isn’t pleased, either, with the tattered state of the Democratic Party’s progressive wing. “The Left is totally co-opted, and Clinton’s domesticated them,” he says. “He had Jesse Jackson giving spin after the Hartford presidential debate and Cuomo praising him, but for what? They didn’t even get to speak in prime time at this year’s Democratic Convention. There was no debate at the convention. The Democratic Party is like the politburo in Russia. It’s strictly run by pollsters to curry the favor of campaign donors.

“It’s quite remarkable, the state of moral bankruptcy of the Democratic Party.”

Sounding closer to Noam Chomsky and Alexander Cockburn in 1996 than to his former Democratic comrades Dianne Feinstein and Dick Gephardt isn’t what one might have predicted for a man who, as governor of California from 1973 to 1981, once likened his job to paddling a canoe, “sometimes paddling on the left, sometimes on the right,” to keep the boat of state afloat. But while many cynics predicted that Brown’s 1992 run was a quixotic aberration that would quickly be followed by a servile return to the Democratic fold, Brown has instead moved ever further away from the political mainstream. He’s kept the 1/800 number he incessantly flogged in debates (1/800/426-1112 for the curious), but moved the daily radio show he started at the same time from the commercial ABC network to the venerable leftish Pacifica radio stations (Brown’s show runs locally from 4 to 5 p.m. on KPFA, 94.1 FM).

Brown, who during his stint as governor spurned the official mansion in Sacramento for a small apartment with a futon on the floor, has likewise sold the plush, converted fire station he once called home in San Francisco and moved into a warehouse turned live/work space across the street from Oakland’s Amtrak station, where he now hosts biweekly potlucks, discussion groups, tai chi classes, and community meetings on such topics as “The CIA Contra Crack Connection” and “Beyond Politics and Media as Usual.”

SO FIERCELY did Brown embrace his outsider status in 1992–champion the cause of political reform and rail against the corrosive role of money in politics–that it became easy to forget that this was the same man who, scarcely two years before, had been chairman and chief fundraiser for the California Democratic Party, not exactly a bastion of reformism and progressive activism.

But before an interviewer can ask a pointed question about his lightning switch from party hack to crusading outsider, Brown’s already there, making the connection himself. As he explains it, while there wasn’t a Saul-on-the-road-to-Damascus moment of clarity and conversion, the stint as Democratic Party chair played a major role in Brown’s disillusionment with politics as usual.

“I certainly had the experience of being party chairman and raising a lot of money,” he recalls, “and then the general reception by the party insiders was ‘Oh, you didn’t raise enough money, so Feinstein didn’t beat Wilson.'”

Clearly, Brown was stung by the widespread blame he received for failing to mobilize resources in Dianne Feinstein’s hard-fought gubernatorial race against Pete Wilson. “Forget whether victory was possible–I don’t think it was, I think Wilson would have won regardless,” Brown says, pointing instead to the larger implications of the criticisms. “What their statement implies is that I wasn’t corrupt enough, I didn’t do enough to buy and sell and engage in this form of bribery by currying favor with enough special interests. I thought I had done enough of that [fundraising] already, but they said you have to dive deeper into the pools of corruption. And at that point I said that doesn’t work. That was the point at which I decided to run for president and set the $100 limit, so the elite couldn’t participate in it.

“A hundred dollars won’t even pay for valet parking,” Brown snorts, with all the disgust of a man who’s attended one too many $1,000-a-plate fundraising feeds. “That created the gulf between myself and the Democratic Party establishment. And that’s where I am today.”

Brown motions around the room, set off in a corner of his year-old home and headquarters for We the People, the political reform organization he founded from the remnants of his presidential campaign. Padding around the airy, sky-lit space in his battered running shoes and casually shaving himself with an electric razor while talking to staffers, a photographer, and this reporter, the Brown of 1996 displays a lack of pretense and a sly, earthy wit that’s disconcerting coming from the former governor of 23 million people and the world’s eighth largest economy–even an ex-guv with Brown’s reputation.

When I mention the name of a college friend whose wedding Brown recently attended, he grins and declares: “Oh, you must have gone to UC Santa Cruz. One of those pot-smoking environmentalists, are you?”

And Brown’s comment isn’t the only thing around to remind me of Santa Cruz. With its long, communal eating tables, rooftop organic garden, bulletin board full of study session and political rally listings, and retro-’60s, comradely vibes, the We the People building resembles nothing so much as one of that college town’s numerous activist-oriented collective living houses, only with a lot more money and a better architect behind it. All it lacks is a corporate crime-fighting lab in the basement and an alternative fuel-powered Batmobile parked out back to be every lefty crusader’s ultimate dream domicile.

Brown also keeps busy on the lecture circuit–he’ll be at Sonoma State University on Oct. 21–and writes a monthly column on politics for Spin magazine. Ironically enough, Brown’s column is illustrated by Winston Smith, the same artist who provided visual accompaniment for the Dead Kennedys’ 1980 anti-Brown anthem, “California Über Alles,” which imagined the then-governor as a “Zen fascist” president, forcing children to meditate in school and sending the un-cool off to concentration camps to be exterminated by “organic gas.”

But even the Dead Kennedys’ lead singer, Jello Biafra, later changed his mind about Brown, saying in 1992: “I’m considering endorsing him for president,” as did Chicago columnist Mike Royko, who retracted the “Governor Moonbeam” sobriquet he’d once coined.

Waiting for the photographer to set up, Brown wanders over to the office end of We the People headquarters to discuss some matter with Sarah Wellinghoff, one of his group’s three paid staffers. Just how charmingly shoestring an operation this is becomes clear when Brown extends me an invitation to an upcoming speaking event. “Whom do I call to make arrangements with?” I ask, expecting to be foisted off on an aide or camp follower. “Oh, just me,” replies Brown.

So much for the trappings of power. I take the lull in the conversation as an opportunity to poke around the building’s conversation space/entertainment center, looking atop the massive big-screen television (used no doubt only for screening earnest political documentaries about exploited Third World peasants, and never for lighter explosion-fests like Terminator 2) at the former governor’s CD collection, hoping to glean insights into his character. Music taste often provides a window to the listener’s soul, and it’s tempting to equate the Beethoven and Bach with Brown’s Jesuit-trained, Yale-educated analytical side, the Kate Bush with his sensual, Esalen workshopattending and Linda Rondstadtdating side, and American Music Club with . . . oh, never mind. The records probably belong to someone else, anyway.

And before I can make it to the kitchen space to surreptitiously inspect the cupboards for contraband Hostess products and Coco-Puffs hidden behind the brown rice and barley, Brown is back, speaking about the experiment in communal living and working he’s engaged in as a living embodiment of the values he supports. “That’s why we’re here,” he says, “that’s why we’re living and working together, and why we have the radio show.

“We want to be sustainable, convivial, and working for a just future.”

Brown admits that We the People is still a work in progress. “Definitely,” he says. “There is not a blueprint at this point for what we’re trying to do. But I believe that as the ugliness of the current regime becomes manifest, individuals will be inspired, throughout America and throughout the world, to organize an effective resistance.”

Actually, admits isn’t the right word. One of Brown’s more appealing traits has always been his willingness to say openly that he doesn’t have all the answers, as when he describes the difficulty of fighting the hydra-headed corporate beast he rails against: “It’s very hard, but it may be that as the supply lines expand, space may open for local initiative.

“It’s true that McDonaldization is spreading throughout the world, namely a centralized, uniform distribution system. Is there room amongst all that for a local hamburger shop anymore? We’ll see. At the very moment when a large structure seems to have triumphed, cracks appear and preferences arise that demand something more human, more original, more face to face, more creative.”

So amid all the gloom, does Brown see any signs of effective struggle and resistance? “Many signs,” he replies. “People engaging in home schooling. People doing socially responsible business. Cooperative communities. Alternative media. Organic permaculture. There are green plans different cities are creating. People fighting the rape of the Headwaters, where a thousand were willing to get arrested. Those are very hopeful signs that people are fighting against an inhuman structure that does not reward virtue. Return on investment is not a valid criterion for civilization.”

PRESSED TO DESCRIBE positive aspects of the state of mainstream politics in 1996, Brown has a more difficult time. “Pathetic,” is how he describes campaign ’96. “Dangerously irrelevant. Exhibit A would be the failure to discuss the state of race relations in the country, and the failure to honestly address the falling standard of living for vast numbers of American people, and the failure to confront the ecological disasters that are building up for all humanity.”

But what about the newly revived AFL-CIO and its efforts to influence countless House races through a massive advertising and get-out-the-vote blitz? Surely that’s a hopeful sign for a labor-friendly lefty like Brown, isn’t it? “You can look at that glass as half full or half empty,” Brown replies, sounding as though he’d rather ask why one would use something as primitive as a glass at all. “If they unleash their organizing skill at Clinton to demand accountability and push him toward labor law reform after the election, it’ll be fine, but if they think that simply by electing Democrats they’re accomplishing something, then it’s just status-quo politics.”

Ambivalence toward the Democratic Party is certainly an emotion Brown is familiar with, and he empathizes with progressives like Jesse Jackson who have opted to stick with the “Party of the Ass,” as British politico singer Billy Bragg once called it, and attempt to reform the Democrats from within. “Clinton’s convinced people that Dole will be worse, and that’s an intellectual debate you can have,” he says. “Jackson thinks that the people who he cares about will be better off under a Clinton presidency, and you can make the argument that if Clinton is re-elected, progressive people and groups can put pressure on him to achieve things that wouldn’t be possible in a Dole presidency. Opening up the CIA, pressing for more labor reform, pressing environmental issues, rebuilding the cities–Clinton will have a hard time resisting that, if there’s a progressive power base that gets ignited.

“I just feel that to go to that convention and lend one’s integrity to what’s essentially a lie doesn’t feel right.”

BROWN DESCRIBES his current ties to the party for which he thrice sought the presidential nomination–in 1976, 1980, and 1992–as “just the ties of who I am, what I’ve done, and what I might do in the future,” and leaves open the perennial possibility of joining third-party politics.

“Whatever will work,” Brown says. “A new party for a new millennium? That sounds very attractive. Whether it will work or not remains to be seen, or whether this 170-year-old horse called the Democratic Party can have new life breathed into it. I’m dubious, but I’ll leave it as an open question for now.”

Eschewing direct participation in electoral politics for the moment, Brown prefers to continue working on grassroots, We the People projects. “Expanding the radio show to new cities and launching the We The People law firm” are what Brown describes as his top priorities. “We’re about to file a lawsuit against some wrongdoers. And we’re scheduling more events, and working to join with other groups who want to create an alternative power base to the two-party scam.

“You could call what we’re after a call for perestroika in the American context,” Brown adds. “But I hope what happened to Gorbachev doesn’t happen to me.”

Brown pauses a moment, maybe considering the fate of another slightly aloof intellectual/political leader who led his homeland through hardships, only to be muscled aside by a puffy-faced, more cutthroat rival, then to eventually find redemption and renewed purpose in the activist arena.

“Or perhaps,” he adds, “it already has.”

Jerry Brown will speak at Sonoma State University on Monday, Oct. 21, at 8 p.m. in the Evert B. Person Theater. Tickets are $7 general/$5 students presale, $10 general/$7 students at the door. Call 664-2382 for more information. There is also a We the People website.

From the October 17-23, 1996 issue of the Sonoma Independent

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

© 1996 Metrosa, Inc.