Power Lunch

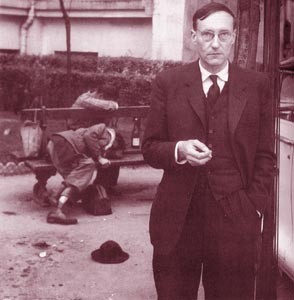

Dead beat: Before his 1997 death, beat-era author William Burroughs shook the writing establishment with such provocative prose as Naked Lunch and Junky.

New book examines early works of beat-era author William Burroughs

By John Sinclair

WRITERS ARE, in a way, very powerful indeed,” William Burroughs once noted. “They write the script for the reality film. Kerouac opened a million coffee bars and sold a million pairs of Levi’s to both sexes. Woodstock rises from his pages. Sometimes, as in the case of Kerouac. the effect produced by a writer is immediate, as if a generation were waiting to be written.”

But despite–or is it because of?–their enormous impact on the cultural life of the second half of the 20th century, the great American author William Seward Burroughs and his contemporaries Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg were despised and reviled by the literary establishment for most of their creative lives.

Even now, the vast body of innovative literature created by this holy trinity of the Beat Generation is scorned by the academy and mainly denied its seminal influence on the course of creative writing since 1950, let alone its central role in the development of modern consciousness.

But the enlightened legion of Beat literature enthusiasts is nothing if not persistent, contributing massive biographies like Ginsberg, Memory Babe (Kerouac) and Literary Outlaw (Burroughs), and stunning collections of excerpts from their works designed to introduce contemporary readers to the high quality, artistic scope, and apocalyptic intensity of their writing.

Now we must add the newly published Word Virus: The William S. Burroughs Reader (Grove Press, $27.50), lovingly assembled by James Grauerholz and Ira Silverberg, to The Portable Jack Kerouac, the thrilling compilation edited by Ann Charters, and The Collected Poems of Allen Ginsberg, as essential texts for understanding the modern era, the cultural revolution of the ’60s and the postmodern nightmare prophesied in their writings.

Slowly emerging against the barren cultural landscape of America in the ’50s, the iconoclastic early works of Kerouac and Burroughs did not reach publication until several years after their composition. On the Road, Kerouac’s sensational portrait of America at the turning point, was set in the late ’40s, written in 1952, but not published until 1957. Naked Lunch, Burroughs’ visionary tour de force begun in 1954-55, didn’t see the light of day in the United States until 1962. Neither would have met their wildly responsive public without the tireless efforts of Allen Ginsberg, who persisted in presenting the manuscripts of his friends to publisher after publisher until success was finally assured.

Burroughs met Ginsberg and Kerouac in the early ’40s, when the younger men were students at Columbia University and Burroughs an anomalous inhabitant of the seedy underbelly of Manhattan who had left behind an upper middle-class upbringing in St. Louis and a Harvard degree for the life of a petty hustler and dope fiend without a single literary ambition. Only through the constant urging of Kerouac and Ginsberg, both committed from an early age to writing as a means of immediate personal expression, was Burroughs finally persuaded to take up pen and typewriter around 1949.

“Until the age of thirty-five, when I wrote Junky, I had a special abhorrence for writing, for my thoughts and feelings put down on a piece of paper,” he wrote in “Lee’s Journals” (1955). “Occasionally I would write a few sentences and then stop, overwhelmed with disgust and a sort of horror. At the present time, writing appears to me as an absolute necessity.”

Burroughs may have started late, but once he committed himself to writing he enjoyed a long and productive literary life until his peaceful demise at age 83 in 1997. His first novel, Junky: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict, a straightforward account of his experiences as a heroin addict in the small-time criminal underworld of ’30s and ’40s America, was published as a garish paperback (coupled with an anti-narcotics tract). His second, Queer, reported the author’s adventures in the homosexual underground of the period and was deemed unpublishable.

Hereafter, Burroughs’ writing would be obsessed with seeking solutions to the fundamental problems of modern life. He would juxtapose direct reporting of present conditions with fantastic passages satirizing human degeneracy and futuristic depictions of scenes from an intergalactic life-and-death struggle between the forces of intelligence and the agents of evil and greed. Sections of the novel that Kerouac named Naked Lunch–“a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork”–were retyped and assembled by Ginsberg and Kerouac into a package of pure literary dynamite that exploded the boundaries of modern fiction upon its publication in 1962.

“This novel is a scenario for future action in the real world,” Burroughs wrote in “Ginsberg Notes” (1955). “Junky, Queer, ‘Yage [Letters]’ reconstructed my past. The present novel is an attempt to create my future. In a sense it is a guidebook, a map.”

By the time Naked Lunch was completed, Burroughs had intuited that the sickness at the heart of Western civilization seemed to be rooted in the very language itself, a fairly recent development–say 10,000 years at best–in the 500,000-year evolution of the human species. With the painter Bryon Gysin he invented what he called the “cut-up method,” literally scissoring diverse texts and taping them together at random to create new passages that could be eerily prescient or incomprehensibly banal, but unmistakably added a new edge to his writing.

Word Virus provides generous samples of Burroughs’ mature work, from Naked Lunch, Soft Machine, and Nova Express to Cities of the Red Night, The Place of Dead Roads, and The Western Lands–the latter three being the Red Night Trilogy, completed in 1987, that was his final major achievement as a writer. Excerpts from The Job, The Adding Machine, The Wild Boys, Exterminator!, and the remarkable late works The Cat Inside and My Education: A Book of Dreams complete the picture first sketched out in Burroughs’ earliest writings–a pair of collaborations with Kells Elvins (“Twilight’s Last Gleaming,” 1938) and Jack Kerouac (“And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks,” 1945)–and the first two novels, Junky and Queer.

Perhaps most spectacularly, Word Virus presents us with the opportunity to follow the progress and development of one of the most brilliant minds of the 20th century as its ceaseless workings manifest themselves in his writing. Particularly illuminating are Burroughs’ mid-’50s musings, collected in The Yage Letters, “Lee’s Journals,” and “Ginsberg Notes,” where he begins to understand his mission as a writer and to accept the awful consequences of its pursuit, which will be evidenced in the pages of his mature works, such as “Remembering Jack Kerouac” (1969): “[W]riters are trying to create a universe in which they have lived or where they would like to live.

“To write it, they must go there and submit to conditions that they may not have bargained for. In any case, by writing a universe, the writer makes such a universe possible.”

THE BIOGRAPHICAL passages written by James Grauerholz to title and introduce each section of Word Virus provide an extremely useful exegesis of Burroughs’ life and work, rooting the writing in the details of geography and circumstance that shaped the writer’s peculiar consciousness. And Burroughs himself makes the writings come alive on the bound-in 23-minute CD of excerpts from John Giorno’s magnificent four-disk compilation for Mouth Almighty Records’ The Best of William Burroughs.

There was nothing quite like hearing the old master inhabit his bizarre characters and bring them to life in his concert performances and readings, but this is just as close as you can get now, and the recordings are going to last a long, long time.

His novels and other writings, too, will be around as long as there is literature, and Word Virus will lead you without fail into the complicated universe created for us by William Seward Burroughs.

In 1965, poet, deejay, and bandleader John Sinclair wrote his master’s thesis on Naked Lunch for Wayne State University.

From the March 4-10, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.