Indie Spirit

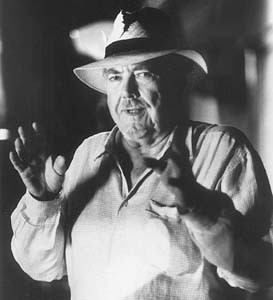

Robert Altman blasts Hollywood and discusses his new film, ‘Cookie’s Fortune’

By Nicole McEwan

I DON’T HAVE personality problems,” says director Robert Altman, referring to the notoriously troubled relationship he’s maintained with Hollywood over his long career making such critically acclaimed films as The Player. “I’m no maverick. It’s quite simple. The major studios and I and the business that they’re in are simply incompatible. I can’t make those films they sell, and they can’t sell the films I make with the machinery they have set up. Essentially, they sell shoes, and I make gloves.”

Because our conversation takes place only two days after the Oscars, the talk inevitably turns to that Hollywood institution. The 74-year-old director, speaking by phone from his office in Manhattan, bluntly compares this year’s Best Picture upset to the Holyfield/Lewis boxing debacle.

“It’s so wrong, boring, self-congratulatory, and fixed,” Altman says. “It’s not like someone actually puts money in your pocket to buy your vote; they just assault you with ads, which should be banned. Of course, that’s what Oscar is all about: advertising. It’s not about truth or any real thing. It’s not about the actual craft and it never will be.”

As for Shakespeare in Love, Altman goes on to describe Miramax, the company behind the evening’s biggest winner, as a “scavenger which picks up work when it’s already half-finished.”

In the year when George Lucas is releasing a large, but limited amount of Star Wars prints to ensure long lines at the multiplex, Altman’s cynicism about the economics of the business that has only sporadically embraced him seems less sour grapes and more harsh reality. It’s hard to avoid feeling that American cinema has become much like designer jeans–presold in splashy ads with A-list stars stamped on movie posters like corporate logos.

“This whole trend started in the ’50s,” Altman says. “Studios started telling us how much money they were making. Before then the public never thought about cost, profit, or loss. Now that’s all you hear about. It’s a different type of marketing. I have to laugh–or else I’d cry.”

This weekend, the director’s own new film, Cookie’s Fortune, hits theaters across the country, fresh from its showing in February at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival. Before a cheering crowd at the Utah festival, Robert Redford introduced the director with a heartfelt observation: “When one thinks about the definition of independent film and what it means, in my mind there is no greater example of that than Robert Altman.”

Altman quickly stirred the audience to laughter with his reply: “I was given a great opportunity 30 years ago, at what used to be the best festival, and it’s still OK. They call it Cannes.”

The year was 1970, and the tenacious Kansas City-born director had survived two decades of on-and-off work as a bit actor, writer, and TV series director. His first two films, Delinquent( 1957) and Countdown (1968), bookended that long climb. Then came M*A*S*H, the blissfully irreverent satire of the daily lives of Korean war medics. The film earned him the Palm d’Or at Cannes and an Oscar nomination for best director.

Suddenly the former World War II bomber pilot, ex-engineering student (he invented a machine for tattooing IDs on dogs), and insurance salesman was hot property. Having once said, “Filmmaking is a chance to live several lives,” Altman had already lived at least a dozen.

In the 30 years since, Altman’s output has included modern classics like McCabe and Mrs. Miller and Short Cuts, with numerous small gems, such as The Long Goodbye, strewn along what Altman calls his “journey.”

Cookie’s Fortune, his 31st film, stars Glenn Close, Julianne Moore, Patricia Neal, and Liv Tyler as three generations of women in the antebellum South. Like Ready to Wear, it’s a murder mystery with no murder. It’s also a Southern Gothic comedy of errors that gently spoofs Tennessee Williams while pointing a moralistic finger at “genteel” society.

Hardly a careerist, Altman takes on only those films that interest him. He chose Cookie for the ironic opportunities its setting presented.

“I love to look at these small towns in America where everybody knows exactly what everyone else is doing, yet they all pretend to know nothing,” he explains.

UNLIKE such mad perfectionists as Alfred Hitchcock, Altman has a technique that might best be described as jazzlike in its improvisational quality. Casting, he says, is “90 percent of the job. Once that process is done, I pretty much turn the work over to the actors. I don’t like to get in the way. If a film wound up coming out the way I envisioned it in the beginning, it wouldn’t be a very good film. So it’s a surprise. How can I sit there and ask the audience to be surprised if I myself am not?”

Surprisingly, though his career has spanned five decades and at least three so-called comebacks, the director has few regrets, other than losing Ragtime to Milos Forman in 1980.

“I know that there’s not a filmmaker alive, nor has there ever been, who has had a better shake than me,” Altman says. “I have never been without a project that I chose, [a project] of my own creation.

“Meanwhile, the press will come along and say, ‘Oh, God–the ’80s, where’d you go? Your career just crashed. … Did you have to eat off the street or what?’ My response is, ‘Well, I was doing great stuff, you just didn’t see it.’ To me those films that are dismissed by the general ‘publicity’–I just don’t see them from that negative standpoint, so I really don’t know how to answer those questions.”

Philosophically, he adds: “Really, there’s only one person who can like all my films, and that’s me.”

Relentlessly energetic, Altman is already preparing Mr. T and the Women–a comedy about a “pussy-whipped gynecologist.” He’s also at work producing Alan Rudolph’s follow-up to Breakfast of Champions, which has its U.S. premiere at the Rafael Theater in San Rafael on April 16 (see Film listing in calendar for details).

“The main thing which saves me is that I’m always working,” Altman says. “All that shit disappears and I’m really with the people I love. I’m creating, the actors are exploring, and the whole process is exciting. Overall, it’s a great way to spend one’s life.”

From the April 15-21, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.