‘Explosive Acts’ captures the debauched atmosphere of 1890s Paris

By Christine Brenneman

IF ONE PERSON serves as an emblem of the turbulent, debauched atmosphere of 1890s Paris, it’s artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. He may have been a cripple, an alcoholic, and a syphilitic, but Toulouse-Lautrec was enormously connected to both the important figures of the arts community and the sleazy entertainers and prostitutes of fin-de-siècle Paris.

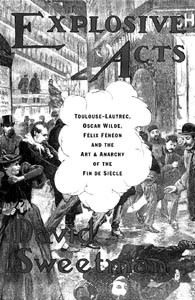

In David Sweetman’s Explosive Acts: Toulouse-Lautrec, Oscar Wilde, Félix Fénéon, and the Art and Anarchy of the Fin de Siècle (Simon & Schuster; $35), we gain entry into this swirling world of anarchists, artists, and whores.

But don’t be fooled by the expanse of the title: Toulouse-Lautrec is the hobbling axle around whom all the action revolves.

Sweetman traces the arc of Toulouse-Lautrec’s short existence, starting with his odd family life as a semi-aristocratic youth in the French countryside.

His parents were first cousins, which was most likely the cause of his health problems from the start. A doting mother couldn’t compensate for his estranged father, who wanted nothing to do with his small, crippled son. Thankfully, they had the foresight to send him off to Paris when he displayed enormous artistic potential.

This, of course, is when the story gets interesting. Toulouse-Lautrec studied art at a number of notable ateliers, but he also quickly fell in with a rambunctious, liberated crowd that included other artists and writers.

His family considered these rapscallions far too louche for their supposedly well-bred son, but this mattered little to Toulouse-Lautrec. He and his newfound friends embraced the dark underbelly of city life, much as reckless children far from home have always done.

At this point he encountered two things that he would love all his life, but that would ultimately prove to be his undoing: alcohol and prostitutes.

He hung out at bars and in maisons closes (whorehouses) and found that he felt quite comfortable in these lower-class environments.

His art began to reflect this fascination with working-class Paris, depicting real-life views of it. He created portrayals of entertainers and prostitutes from this point forward, all rendered with his signature empathy and candor.

This style and subject matter–which was considered entirely radical and subversive at the end of the 19th century–drew the attention of others who were hell-bent on upsetting the social and artistic status quos of this time, namely Oscar Wilde and Félix Fénéon.

In an intriguing interweaving of these three individuals, Toulouse-Lautrec made art, critic Fénéon wrote about this art, and Wilde read what Fénéon had written.

Wilde and Fénéon pop up intermittently throughout Explosive Acts, rounding out Sweetman’s idea that Toulouse-Lautrec was surrounded by like-minded, anarchist types.

Unfortunately, what begins as an exceedingly well-researched chronicle of Toulouse-Lautrec soon becomes an attempt to squeeze this entire era into one book. We are given detailed accounts of Toulouse-Lautrec’s every acquaintance, Wilde’s numerous paramours, and Fénéon’s writing career.

Although interesting, this wealth of information sometimes feels overwhelming.

Sweetman’s knowledge is clearly extensive, but too many tangents take away from his earnest campaign: that people should take Toulouse-Lautrec’s art seriously. But don’t we already consider him a truly great, if notorious, figure?

Whatever your opinion about Toulouse-Lautrec’s art, the story of the man and his compatriots, Wilde and Fénéon (and the myriad cast of characters from this epoch), still makes for an entertaining read when told by Sweetman.

It’s impossible to deny that these often outrageous and always brilliant individuals had personality in excess. Maybe that’s why, 100 years after their deaths, their tales are still riveting .

From the April 20-26, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.