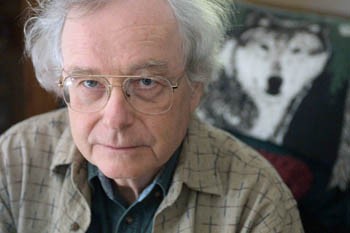

Exotic battleground: Ralph Metzner, editor of Ayahuasca, an anthology of scholarly and first-person accounts of the yagé experience, says there are anecdotal reports of the complete remission of some cancers after one or two ayahuasca sessions. Yet the drug is at the heart of the anti-drug wars.

Vision Quest

Shamanism vs. capitalism: The politics of ayahuasca

By Martin A. Lee

WANDER long enough through the bustling passageways of any crowded village marketplace in the northwest Amazon and you’ll come upon herbalist stands with dried plants, hanging animal parts, and lots of bottled medicines. Among the local offerings you’ll inevitably find “ayahuasca,” a fearsome, foul-tasting, jungle brew sold by the liter.

Pronounced “ah-yah-waska,” the word is from the Quechua language; it means “vine of the soul,” “vine of the dead,” or “the vision vine.” Known by various names among 72 native ayahuasca-ingesting cultures in Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador, this legendary, industrial-strength hallucinogen is used by curanderos, or witch doctors, to heal the sick and communicate with spirits. Many rainforest shamans simply refer to ayahuasca as el remedio, “the remedy.”

Revered by indigenous people as a sacred medicine, a master cure for all diseases, it is without a doubt the most celebrated hallucinogenic plant concoction of the Amazon. But it’s also under threat from both anti-narcotics agencies and corporations that want to patent it and corner the market on its use.

Plant Teachers

Long ago, South American Indian medicine men and medicine women became adept at manipulating an array of ingredients that were mixed and boiled into ayahuasca, or “yagé,” as it is often called. An elaborate set of rituals governed every step of the process, from gathering leaves, roots, and bark to cooking and administering the intoxicant.

Ayahuasca is unique in that its powerful psychopharmacological effect is dependent on a synergistic combination of active alkaloids from at least two plants–the Banisteriopsis caapi vine containing the crucial harmala alkaloids, along with the leafy plant Psychotria viridis or some other hallucinogenic admixture that contains dimethyltryptamine (DMT) alkaloids.

Most curious is the fact that when taken orally, DMT is metabolized and deactivated by a particular gastric enzyme. But certain chemicals in the yagé vine counter the action of this stomach enzyme, thereby allowing the DMT to circulate through the bloodstream and into the brain, where it triggers intense visions and supernatural experiences.

Contemporary researchers marvel at what chemist J. C. Callaway describes as “one of the most sophisticated drug delivery systems in existence.” Just how the Amazon Indians managed to figure out this amazing bit of synergistic alchemy is one of the many mysteries of yagé.

The ayahuasqueros, the native healers who use yagé, will tell you that their knowledge comes directly from “the plant teachers” themselves. Hallucinogenic botanicals are viewed as the embodiments of intelligent beings who become visible only in special states of consciousness and who function as spirit guides and sources of healing power and knowledge.

According to indigenous folklore, ayahuasca is the fount of all understanding, the ultimate medium that reveals the mythological origins of life. To drink yagé, anthropologist Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff once wrote, is to return to the cosmic uterus, the primordial womb of existence, “where the individual ‘sees’ the tribal divinities, the creation of the universe and humanity, the first couple, the creation of the animals, and the establishment of the social order.”

The Great Cleansing

Ayahuasca was never used casually or for recreational purposes in traditional societies. Only a ritually clean person who maintained a strict dietary regimen (low on spices, sugars, and animal fat) for several weeks or months was deemed ready to partake of the experience. Shamanic initiation rites entailed a lengthy period of preparation, which included social isolation and sexual abstinence, before novices got to ingest yagé with the curandero.

A connoisseur of the chemically induced trance state, the curandero provides guidance to those who wish to embark upon a “vision quest.” But rainforest shamans typically “resist the heroic mold into which current Western image-making would pour them,” says anthropologist Michael Taussig. Instead, they often exude a bawdy vitality and a funny, unpretentious, down-to-earth manner.

More of a trickster than a guru or saint, the curandero is unquestionably the master of ceremonies, the key figure in the ayahuasca drama. After nightfall, the bitter brew is passed around a circle from mouth to mouth, and the shaman starts to sing about the visions they will see. Listening to his chant, the novices feel some numbness on their lips and warmth in their guts.

A vertiginous surge of energy envelops them. And then all hell breaks loose: retching, vomiting, diarrhea–an unstoppable high colonic that penetrates the innards, sweeping through the intestinal coils like liquid Drano of the soul, cleansing the body of parasites, emotional blockages, long-held resentments. It is for good reason that Amazonian natives refer to la purga when speaking of yagé.

“One cannot help being impressed by the remarkable health-enhancing effects attributed to the purging action of the vine,” writes Sonoma-based psychologist Ralph Metzner, editor of Ayahuasca, an anthology of scholarly and first-person accounts of the yagé experience. Metzner notes that there have been anecdotal reports of the complete remission of some cancers after one or two ayahuasca sessions. The rejuvenating impact of la purga would help explain the exceptional health of the ayahuasqueros, even those of advanced ages.

“Space/Time Travel”

After the unavoidable episode of purging, the senses liven up and the initiate experiences a kind of “magnetic release from the world,” as Wade Davis, author and explorer in residence with the National Geographic Society, puts it. This is followed by an onslaught of spectacular visions, a swirling pandemonium of kaleidoscopic imagery that changes faster than the speed of thought.

While under the influence of ayahuasca, it is not uncommon for people to feel as though they have been lifted out of their bodies and catapulted into a strange, aerial excursion. During this voyage to far-off realms, they see gorgeous vistas and enchanted landscapes that suddenly give way to harrowing encounters with fierce jaguars, huge iridescent snakes, and other predatory beasts intent on devouring the novice.

William Burroughs described the sensation of long-distance flying when he took ayahuasca during an expedition in South America in 1953. “Yagé is space time travel,” he wrote in a letter to Allen Ginsberg. “The blood and substance of many races, Negro, Polynesian, Mountain Mongol, Desert Nomad, Polyglot Near East, Indian–new races as yet unconceived and unborn, combinations not yet realized pass through your body. Migrations, incredible journeys through deserts and jungles and mountains . . . A place where the unknown past and the emergent future meet in a vibrating soundless hum.”

It is not known why the visions provoked by ayahuasca often involve Amazon jungle animals, even when people from other continents swallow the acrid tonic. Stories of anacondas the length of rivers and electric eels that light up the night sky are classical elements of the yagé experience. Heinz Kusel, a trader living among the Chama natives of northeastern Peru in the late 1940s, recounted how an Indian once told him that whenever he drank ayahuasca, he had such beautiful visions that he “put his hands over his eyes for fear that someone might steal them.”

Drug Wars in the New World

Indeed, there was a time when people did try to steal the visions. Ever since the European invaders came to the New World more than 500 years ago, they scorned and demonized ayahuasca and other hallucinogenic substances that were employed by native peoples in their healing rituals.

Western knowledge of yagé ceremonies was first recorded in the 17th century by Jesuit missionaries who condemned the use of “diabolical potions” prepared from jungle vines. The ruthless attempt to eradicate such practices among the colonized inhabitants of the Americas was part of an imperialist effort to impose a new social order that stigmatized the ayahuasca experience as a form of devil worship or possession by evil spirits. But the ingestion of yagé for religious and medicinal purposes continued, despite the genocidal campaigns of the conquistadors.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that Richard Evans Schultes, director of Harvard University’s Botanical Museum, provided a scientific analysis of the complex ethnobotany of yagé and many other psychoactive plants in the Amazon region. By this time, the shamanic use of ayahuasca had spread from remote jungle areas to South American urban centers, where mestizo curanderos added a Christian gloss to archaic Indian ceremonies. Several Brazilian churches started to administer ayahuasca as a sacrament in a syncretic fusion of Catholicism and shamanism.

The two largest of these church movements–Santo Daime and União de Vegetal–utilized yagé in their religious services without interference by the Brazilian government until the mid-1980s, when U.S. officials pressured Brazil’s Federal Council on Narcotics to put the Banisteriopsis caapi vine on a list of controlled substances. The ayahuasca churches protested, and a government committee was appointed to investigate the matter. After examining the churches’ use of yagé and testing it on themselves, the members of this committee recommended that the ban on ayahuasca be lifted.

The Brazilian government acted upon this recommendation and legalized the sacramental use of yagé in 1987, much to the dismay of the U.S. Embassy.

Resurgent Shamanism

The revival of shamanic rituals found a fertile ground, particularly in areas where wealthy plantation owners and multinational corporations displaced peasants from the land. For these poor and desperate people, ayahuasca was a gift that helped them cope with the expansion of the market economy into the frontier. As their subsistence society unraveled, so, too, did their sense of sanity and well-being.

Consequently, a growing number of mentally ill individuals and uprooted wage laborers sought out curanderos, who were forced into a new role. In addition to curing the sick and communicating with the spirit world, many witch doctors began using ayahuasca to mediate class conflict. As one Putumayo medicine man told Michael Taussig, “I have been teaching people revolution through my work with plants.”

The more big business encroached upon native turf, the greater the resurgence of shamanism. And in another ironic twist of globalization, the sacred beverage of the Amazon made its way to Europe and the United States, sending law enforcement into a tizzy.

The Santo Daime religion has taken root in Hawaii and the Bay Area, where yagé sessions are held in secret. This ayahuasca church also has branches in several other countries, including Great Britain, Belgium, France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, and Japan.

In October 1999, successive police raids targeted Santo Daime members in the Netherlands, France, and Germany. The crackdown prompted church representatives throughout Europe to mobilize. They are seeking official recognition of their religion, and they want the sacramental use of ayahuasca to be legalized.

Predictably, U.S. narcotics control officials are opposed to ending the prohibition against yagé, despite Peruvian medical studies that indicate ayahuasca can be an effective treatment for cocaine addiction. The fact that yagé tastes so awful–to the point where some people can’t even bring themselves to swallow it–provides an additional safeguard against those who might use it in a cavalier fashion.

Who Owns Yagé?

The U.S. pharmaceutical industry has also taken an interest in ayahuasca. Loren Miller of the International Plant Medicine Corporation received a sample of the yagé vine from a tribal elder in Ecuador. In 1986, Miller obtained a U.S. patent for a specific type of banisteriopsis caapi with the hope of profiting from the plant’s medicinal properties. The patent, which gave Miller’s company exclusive rights in the United States to breed and sell a new variety of the plant, is due to expire in 2003.

Upon learning what had transpired, the Ecuador-based Coordinating Committee of Native Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) accused Miller of committing “an offense against indigenous peoples” by patenting a sacred plant for his own benefit. “Commercializing an ingredient of the religious ceremonies and of healing for our people is a real affront for the over four hundred cultures that populate the Amazon basin,” declared COICA General Coordinator Antonio Jacanamijoy. COICA proclaimed that Miller and his company were unwelcome in indigenous territories. The State Department considered this warning a death threat against Miller and interceded on his behalf.

The controversy over ayahuasca spilled into the diplomatic arena when the Ecuadorian government refused to sign a bilateral agreement on intellectual property rights with the United States in 1996. Washington countered by threatening Ecuador with economic sanctions. Thus far, the U.S. Senate has refused to ratify the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity that recognizes the property rights of native people. More than 100 countries have signed this treaty, including Ecuador.

While multinational corporations seek to exploit the natural treasures of the Amazon, the destruction of the rainforest continues at an accelerated pace and indigenous ways of life are being threatened. “I feel a great sorrow when trees are burned, when the forest is destroyed,” explained Peruvian shaman and painter Pablo Cesar Amaringo, co-author of Ayahuasca Visions. “I feel sorrow because I know that human beings are doing something very wrong. When one takes ayahuasca, one can sometimes hear how the trees cry when they are going to be cut down. They know beforehand, and they cry. And the spirits have to go to other places, because their physical part, their house, is destroyed.”

Martin A. Lee is the author of ‘The Beast Reawakens’ and ‘Acid Dreams: The CIA, LSD, and the Sixties Rebellion.’ He can be reached at ma***********@***oo.com.

Addendum

In an earlier version of this article, Martin Lee wrote that Loren Miller of the International Plant Medicine Corporation “had pulled out a yagé plant from the garden of an Ecuadorian family without asking permission, hurried back to the United States with the vine, and then applied to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.” This statement, which was based on previously published sources, is incorrect. Mr. Miller was given a sample of the yagé vine in 1974 by a tribal leader in the Ecuadoran Amazon. In 1981 he applied for a patent on a particular variety of banisteriopsis caapi. Mr. Lee erred in stating that Miller’s patent was denied by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. The patent was granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) in 1986, but was challenged in 1999 by the Washington-based Center for International Environmental Law on behalf of COICA. This triggered a see-saw legal battle that culminated in a decision by the PTO to confirm Miller’s patent on January 26, 2001. Mr. Miller maintains that the International Plant Medicine Corporation, which engages in pharmaceutical research, has never commercialized or profited from the yagé vine or the patent. He states that “this patent has been sitting harmlessly in a drawer gathering dust, and that it does not affect the natives’ use of their plants in any way, shape or form.” Mr. Lee apologizes to Mr. Miller and his company for any errors in the original version of this article and regrets any problems that this may have caused.

From the March 29-April 4, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.