A moment of reflection: Marin County environmentalist Huey Johnson says the Sonoma County Water Agency “has run roughshod over honesty and logic.”

Ripple Effect

Welcome to the byzantine world of North Bay water politics

By Janet Wells

‘Whiskey’s for drinking, water’s for fighting.’

–Attributed to Mark Twain

IN SONOMA COUNTY, the deeply entrenched political battles are not really about grapes or redwoods, clogged highways or even sprawl. It’s about water and how Sonoma County has, time and again, put up its dukes, battling litigation, environmentalists, and public scrutiny in order to maintain a stranglehold on the lifeblood resource that sustains the county’s burgeoning growth.

For 50 years, the Sonoma County Water Agency has, according to former Petaluma City Councilman-turned-water activist David Keller, relentlessly pursued its mission “to get access to, get control of, and use as much water as possible.”

Keller was part of a bare majority of the Petaluma City Council last year that, for a short time, rebuked the water agency’s Goliath-like push to expand its water system. That action was overturned earlier this year by the council’s newly elected, less-than-environmentally friendly majority.

What gets Keller–the affable hazel-eyed toolmaker and self-described “moderate from Bolinas”–talking a mile a minute for hours on end is that the $180 million pipeline project at the heart of last year’s confrontation between Petaluma and the SCWA was just one of four major and diverse expansion schemes simmering away on the agency’s burners.

If successful, the projects would be a windfall in the form of billions of gallons of water annually to meet–and critics say encourage–residential, industrial, and agricultural growth in Sonoma and Marin counties. The projects would also have a combined price tag in the hundreds of millions and could have dire consequences for already compromised watershed habitat in Northern California.

Keller–along with a bevy of high-profile environmentalists, legislators, and water resource experts–says the agency has been forging ahead with its plans in a bureaucratic vacuum, with little input from the folks who will end up footing the bills through increased water rates.

“[Water agency officials] seem to be pretty unavailable for public scrutiny in terms of some of their proposals and their plans and where they are going to be spending their money,” agrees Assemblywoman Virginia Strom-Martin, D-Duncans Mills, who has introduced legislation designed to strip the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors of its authority to regulate water issues, as well as force the water agency to drop its drawbridge and invite the public in for a look.

Keller bluntly characterizes water agency tactics as “dishonest,” “disrespectful,” “secretive,” and “childish.” “How we manage our water is really a touchstone for what happens to Sonoma County,” he fumes during lunch at a Petaluma cafe. “I really resent being treated like mushrooms.”

Does he mean being kept in the dark by the water agency? “Yes,” he replies. “And being fed shit.”

Coveting Your Neighbor’s Water

Unlike many regions of arid California–Los Angeles being the prime example–Sonoma County has a source of high-quality water in its backyard. With almost 1,500 square miles of watershed and more than 80 tributaries, the Russian River’s clear, naturally gravel-filtered water flows 84 miles from its headwaters in southern Mendocino County, feeding Sonoma County’s fertile agricultural lands and shady redwood-studded coastline on the way to its ocean outlet at Jenner.

It didn’t take a crystal ball for Sonoma County forefathers to see that the Russian River–with its summer flow down to a trickle in drier years–wouldn’t have ample capacity for the future. And a readily available source of water is key for population growth and agricultural and industrial expansion, which add up to increased revenues and healthy municipal coffers. So, in the hallowed tradition of California’s legendary water wars, the county started stealing its water from somewhere else, dipping its massive bureaucratic bucket into the Eel River in Mendocino County and pouring it into the Russian River in order to quench the thirst of 600,000 residential and commercial water users in Sonoma and Marin counties.

Of course, “stealing” is a relative term under California’s water laws. Known as “appropriative rights,” the law essentially grants water rights to the first person or agency to divert water and use it–which Sonoma County did, way back in 1908, when PG&E started diverting Eel River water into the Russian River to fuel the Potter Valley hydroelectric plant.

The headwaters of the Eel River spill out of a volcanic cauldron surrounded by 7,000-foot-high snow-capped mountains in the southern part of Mendocino National Forest. The river’s main stem and three forks rank as the state’s third largest watershed, covering almost 3,700 square miles as the river winds north for more than 200 miles before draining to the ocean south of Eureka.

To tap this treasure, the SCWA (then the Flood Control and Water Conservation District) was established in 1949 under the Sonoma County Water Act. One of the agency’s first actions was to apply for construction of the Coyote Valley Dam to form Lake Mendocino, mostly with water from the Eel River diversion.

In the byzantine world of water law, the Eel’s value lay not in its abundant water, but in its capacity to provide electricity. Once the diverted water rocketed through the Potter Valley Project’s turbines and out the two-mile-long diversion tunnel, PG&E considered it useless, technically “abandoned.”

Sonoma County was only too happy to adopt the water, scoring–for free–50 to 70 percent of the diverted water to sell to cities and water districts in Sonoma and Marin counties. By doing so, the water agency and the ratepayers have–perhaps unwittingly at first–supported the degradation of 80 miles of the Eel’s once-thriving salmon and trout habitat, since the Potter Valley Project siphons up to 97 percent of the Eel River’s main-stem flow for energy production, diverting some 58 billion gallons of water annually.

Sonoma County also helped deep-six a crucial revenue source for Humboldt County, according to an ongoing lawsuit filed by Friends of the Eel River. “While Sonoma County’s economic fortunes have risen steadily on a wave of urban growth subsidized by vast quantities of cheap water diverted from the Eel River without compensation to that watershed’s inhabitants, Humboldt County’s reliance upon a once-thriving commercial and sport fishery has collapsed,” causing a loss to that county of over $10 million annually, according to the 1999 suit, which was filed in Sonoma County Superior Court against the water agency and PG&E.

Pipeline Expansion: Petaluma City Council vs. Sonoma County Water Agency.

Eel River Diversions: The SCWA maneuvers to control the Potter Valley Project and protect the diversions that bolster Russian River supplies.

Wastewater Distribution: Is the SCWA seeking to control west county sanitation districts?

Water Treatment Plant: The water agency studies the option of building a $500 million surface water-filtration system on the Russian River.

Use It or Lose It

The SCWA doesn’t unilaterally steamroll the environment or the needs of other counties in seeking to expand its water clout. Several agency programs focus on restoration and conservation. Indeed, a block-lettered sign in front of the agency’s modern glass and concrete headquarters on West College Avenue in Santa Rosa notes that the lawn is made verdant by reclaimed water.

Agency researchers and biologists try to give fish a break from the relentless march of urban growth, through state and federally mandated habitat restoration programs. There are staff hydrogeologists who agree that conservation and recycling can be far more effective and cost-efficient than engineering new water sources.

Nevertheless, the agency’s direction over the years has remained fixated on water as an asset to consume and sell. It’s easy to see why: Another quirky facet of water law, which states, in essence, “Use it or lose it,” is a compelling policy motivator.

“There’s a danger to having unappropriated water,” says Sonoma County Supervisor Mike Reilly, who, like his colleagues, is with a quick change of hats also a member of the SCWA board of directors.

“I don’t pretend to be an expert in California water law, but if you have a reserve of water that you don’t have a reasonable projection that you will use within your region, then external regions will come in and take it.”

Translation? Danged if the county–primed for considerable growth–is going to let anyone else have the water. And no doubt, there are those salivating over the Eel River’s development potential. After all, in the 1930s, Los Angeles interloped hundreds of miles north into the Owens River Valley, pretty much sucking it dry. And, 30 years ago, when a dam was proposed–although never built–on the Eel River’s middle fork near Covelo, Los Angeles again galloped north and bought up land there in search of water.

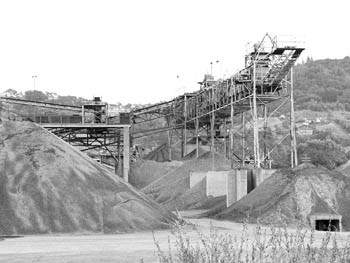

In establishing a firm grip on its water rights, the SCWA has spearheaded several massive public works projects, resulting in two dams and two reservoirs–Lake Mendocino and Lake Sonoma–that hold more than 400,000 acre feet of water (about 130 billion gallons) and sport 79 miles of underground pipeline.

The Coyote Dam, along with transmission pipelines to cities in Sonoma and Marin counties, was financed by a 1955 bond issue for about $14 million. By 1995, payments on the debt totaled almost $25 million, according to a lengthy paper on the water agency written by local environmentalist Krista Rector for the Sonoma County Conservation Center.

Warm Springs Dam–which forms Lake Mendocino–was so controversial that construction was delayed for more than 20 years by litigation, protests, and failed ballot measures. The project was completed at a cost of $360 million. The agency’s debt service will reach more than $6 million a year by 2007, according to Rector’s research, and the debt is scheduled to be retired in 2035.

Interestingly, in 1961–the year before the Warm Springs Dam project was approved by Congress–the water agency’s board won the right to authorize revenue bonds in any amount without a vote of the people, giving the agency an avenue for financing projects without having to kowtow to public approval.

The water agency has continued over the years to march to the same drumbeat of build and expand–and is now in the midst of an ambitious burst of activity, striving to maintain Eel River diversions, as well as expand the agency’s supply and transmission capabilities.

“The water agency here is still gripped by old thinking–control the Russian River, continue to take water out of the rivers because the population is growing,” says Keller, who would like to see far more money and time put into conservation and recycling. “Institutionally, that’s where these guys are. They are a dinosaur as a public agency and as an engineering agency. Their mission needs to shift, and that’s where the crunching of gears is. These guys feel very threatened.”

Keller says his numerous attempts to obtain public documents and information on water agency plans, proposals, operations, and finances have been thwarted repeatedly.

To the fish advocates, the county residents, even the elected officials who have asked questions and raised concerns, the water agency’s attitude has been, says Keller, “Stop bugging us. Do you get your water? Do we take away your wastewater? Then what’s the problem?”

Mum’s the Word

The agency’s honchos do seem unenthusiastic about public scrutiny. There are glossy brochures, with nice maps, photos, and historical information. But there’s minimal information about the agency on the Web, and public information officer Ellen Dowling refers all policy questions to the agency’s director, Randy Poole.

Poole refuses to talk. After terse “no comments” in response to questions about Strom-Martin’s proposed legislation, he says bluntly, “That’s it. I’ve heard the questions”–he actually has heard only two–“I think most of them are for the Board of Supervisors. I’m not going to make any comment on any of it.”

He also declines to discuss the agency and its plans via fax or e-mail, forwarding a list of questions to the Board of Supervisors, who also do not respond.

The water agency–with a staff of 225 and expenditures estimated at $138 million this fiscal year–has fulfilled part of its mission statement, to provide “a safe, reliable supply for growing cities, towns, and agriculture.”

Critics charge, however, that rather than simply meeting the delivery demands of its contractors, the SCWA has actively expedited the consumption and sale of water–making money and stimulating development at the expense of the watershed’s health. Strom-Martin tried to initiate an audit of the water agency’s books last year after the Press Democrat revealed that the agency had spent more than $1 million on lobbying efforts to receive federal funds for fish restoration. Strom-Martin, whose sprawling first Assembly District extends along the North Coast through Mendocino and Humboldt counties, says the agency failed to provide her with a strict accounting of how the funds were used. The morning of the Joint Audit Committee vote none of the committee senators showed up, says Strom-Martin.

“I suspect somebody made a phone call. . . . I did have their votes previously. I personally lobbied,” she says. “This is the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors, who don’t want to give up their power.”

Backed by constituents who say, “Thank God someone is taking on the water agency,” Strom-Martin is trying a different tack this year with her legislation to strip the Board of Supervisors of double duty as water regulators.

The water agency’s board structure is a “huge conflict,” agrees Marin Municipal Water District board member Jared Huffman, whose five-member board is elected. “I have the luxury in Marin of focusing on resource management and water supply without the pressures of being a planning agency,” he says. “You cannot just take off one hat and put on the other and do justice to both.”

Sonoma County Supervisor Reilly defended the board’s water regulatory powers as having logistical benefits, with a “value to being able to coordinate water activities and county public works activities.”

Although Strom-Martin’s proposed legislation has not garnered support from other North Coast legislators–and the Santa Rosa City Council and the city’s Board of Public Utilities both lambasted it as costly and bureaucratic–about 95 percent of the public water districts in California have separately elected boards, Strom-Martin says.

“It’s clear in my mind that this is about good governance and accountability,” she says.

Meanwhile, support for that position is growing. In his recent San Francisco Chronicle opinion piece, Huey D. Johnson, former secretary of the state’s Resources Agency under the Brown administration and now president of the Resource Renewal Institute in San Francisco, went even further: “The Sonoma County Board of Supervisors and their general manager have run roughshod over honesty and logic, and now it is time for a change. It is time to form a separate regional water agency for Sonoma County and time to fire the general manager.”

From the April 5-11, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.