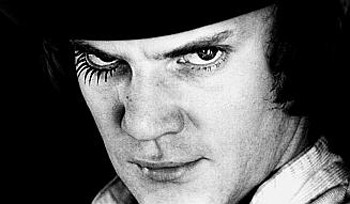

Every Mother’s Son: Malcolm McDowell captured some grand horror in ‘A Clockwork Orange.’

Droog Day Afternoon

Alex is great, but what about Mick?

By

The camera rolls up to a male figure in a white boiler suit and bother-boots, capped with a derby. The derby is just his way of scorning the good behavior of that most well-behaved of all hats. A dandy with a welfare-state future, he holds his glowing white pint of milk, evidently supplied from the same electric dairy that Cary Grant used to scare his wife in Hitchcock’s Suspicion. Ignoring the drink, the lens heads for its target, a glowering eye whose twin is fringed below with obscene little false eyelashes.

“Hi, hi, hi.” The actor Malcolm McDowell, turning up at the Tiburon Film Festival March 11-12, will always be in thrall to his best-known character, Alexander de Large, Alex the droog. As critic David Thomson put it, in Alex we see both Ariel and Caliban–an apt description for a creature invented by a Shakespearean novelist like Anthony Burgess. To the 1971 film version of A Clockwork Orange, McDowell brought the Ariel, and director Stanley Kubrick brought the Caliban. Since that memorable image, McDowell has been a reliable character actor who knows that no matter what movie he’s in, at least five minutes of it will be good. Most recently he stopped the show in the film In Good Company, doing a fine job of flaunt-the-accent-and-collect-the-money.

Admiring McDowell’s nasty insouciance onscreen for decades, I’ve never had such a drastic range of feelings about a movie as I have about A Clockwork Orange. I loved it foolishly then, and I can’t bear it now.

When I was a young nihilist, A Clockwork Orange struck me as an antirevenge movie. It mocked that tradition of “what the movie advertisements refer to as ‘a roaring rampage of revenge,'” as the Bride says in Kill Bill 2. Revenge neither toughened Alex nor incited him to greater crimes. What didn’t kill him just made him want to die.

Still, A Clockwork Orange may be essentially a young person’s film, made particularly for audiences that never needed to fear having their home invaded. Character actor Patrick Magee’s fatuous writer, who gets “the old surprise visit,” only garners as much sympathy as Elmer Fudd would when facing his usual witty, slangy tormentor. It’s not just the droogs’ flamboyant behavior that appeals to the young trouble-fan–their rumbling, stomping and raping; it’s also their love of drugs like vellocet, synthmesc or drencrom (the last probably slang for the late Hunter S. Thompson’s beloved Adrenochrome). Alex the adolescent, haunting his record stores, drunk on sensation, is the one we feel for. He is the only one who isn’t an ape, a victim or a zombie–the missing link between Richard III and Johnny Rotten.

It’s a joke that Alex’s name is Alexander de Large, a tribute to the ultimate megalomaniac (lately cut down to size in Oliver Stone’s miserable epic). Every man’s hand is against little Alex.

This pretty thugs vs. ugly oafs motif is one Oliver Stone tried to get in his similarly divisive Natural Born Killers, a film that also prompted a censorship case in England. (Both A Clockwork Orange and Natural Born Killers were accused of spurring monkey-see-monkey-do killings.) If Stone’s film ended as a lesser cult film it’s likely because of the old movie problem of not enough chemistry; Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis didn’t have a shred of McDowell’s lethal charisma.

As it turned out, England in the 1970s was going to be more short sharp shock than “Ing Soc,” as George Orwell called English socialism in 1984. The droogs’ language is a catchy mix of Cockney street slang and Russian, probably implying the Kremlin’s secret involvement in all this hooliganism. But as we know, our present isn’t the summer of communism; rather, it’s the winter of capitalism. That’s why I still prefer McDowell’s starring role in an epic Candide story that’s as worthy of a second look as A Clockwork Orange.

Why isn’t O Lucky Man! on DVD yet?

Lindsay Anderson’s 1973 O Lucky Man! is a Brechtian musical horror story about England. Again McDowell plays the affable lad going through the mill. The difference is that while Alex jumps, McDowell’s Mick Travis is pushed. Anderson, a noted film critic turned director, had previously led McDowell through If . . . a variation on Jean Vigo’s famed surreal film Zero for Conduct, in which a violent rebellion breaks out against his stodgy and vicious boarding school.

O Lucky Man! is more relaxed. It’s a shrewd and uproarious cabaret movie, animated by a rollicking pub-rock score by pianist Alan Price of the Animals. It begins in the past, a silent, sepia-toned piece of fake Eisenstein homage. McDowell (made l American peon) has his hands amputated for trying to steal a single coffee bean. By the time the story begins in earnest, capitalism has got a little more polite. Still, Mick, an eager-beaver traveling salesman for a coffee firm, has to fight off at least 400 blows.

The proudly left-wing movie is certainly not to everyone’s taste. And calling it a mess can be fair. Yet O Lucky Man! anticipates the mise en scène of The Simpsons. The nice-guy mark of a hero goes down Homer’s road, taking a dozen jobs, facing Frankensteinian doctors, the savageness of the military, time in jail and the excesses of international capitalism at every new bad turn. What keeps McDowell’s kind Mick from being crushed are strange touches of grace from the middle-aged–usually motherly types. The sweetest scene features Mary MacLeod, replaying Rosasharon’s act of charity in the actual ending of The Grapes of Wrath, which Anderson’s beloved John Ford never got to stage in his classic film version.

Like A Clockwork Orange, O Lucky Man! was a movie I saw repeatedly at Los Angeles revival houses like the Fox Venice or the Nu-Art. Once I was fortunate enough to catch it at the Motion Picture Academy’s theater on Wilshire Boulevard. Anderson was there to show the full version, with a sequence cut in America. In this episode, Mick is a social worker failing to talk a poor woman out of gassing herself. Beginning as Alex, McDowell is now at one with Clockwork‘s horrific civil servant Mr. Deltoid, a foolish exponent of a system powerless to help but quite good at hurting.

It was the mid-’70s, times were almost as bad as they are now, and O Lucky Man! went over like free beer. There was, however, a dissenting voice during the Q&A session, which came from a proper English lady in the audience.

“Mr. Anderson,” she said huffily, “Is this your view of England?”

“Madame,” Anderson replied, “to use a British expression–yes, with bells on.”

“Well, I think you should put some sort of warning at the beginning of the film that this is your own view . . .” she began to retort before being quite drowned out.

McDowell’s film had the last word.

Malcolm McDowell appears Friday-Saturday, March 11-12, to be honored at the Tiburon International Film Festival. Friday, McDowell’s newest work, ‘Evilenko,’ is screened at 7pm; director David Grieco and co-star Marton Csokas will also be in attendance. Saturday at 8:30pm, ‘A Clockwork Orange’ is screened. All events at the Tiburon Playhouse Theater, 40 Main St., Tiburon. $8-$10. 415.789.8854.

Select Fest

Themes of all stripes emerge at the TIFF

While there are numerous intentional themes embedded in the programming for the fourth annual Tiburon International Film Festival–including a tribute to Cuba, presentations devoted to peace in the Middle East, sports flicks, political films, animated shorts, a focus on Marin filmmakers and those films that dwell largely on music–there are several presumaby unintentional themes as well.

The oddest of the lot is the ongoing plight of young people saddled with unwanted real estate. In Retreat, for example, four unloving trust-fund babies must decide what to do with their lavishly appointed Maine summer home, riddled as it is with memories of an especially unpleasant governness.

Similarly, in Finding Home, an award-winning new movie co-starring Genevieve Bujold, Louise Fletcher and newcomer Lisa Brenner, a young woman can only create her future by first unlocking her past, all of which is bundled up within the shingled facade of a gorgeous East Coast summer home reeking of stinky memories and demanding a broker.

In Ocean Front Property, a broken-hearted man seeks the solace of four walls and a private dock, clinging piteously to his lease when his ex-fiancée, her new man and a sexy neighbor break the silence. Egads.

Regardless of how sexy the neighbor, one will assume that she’s at least legally employed, unlike a handful of other film-fest fatales who toil at the oldest profession. “What happens when a disenfrancised kid from the suburbs takes a road trip with a prostitute from the city?” pant the filmmakers of Anathema. Something assuredly lurid.

Meanwhile, Zooey purports to tell the true story of an exceptionally attractive (albeit bruised) prostitute and her loser of a husband. And finally, the documentary Hidden Truths focuses on the miserable existence of Nicaraguan prostitutes, women who toil in an illegal milieu that is nonetheless tolerated by a government that will neither help nor condemn them, a film that should shame the makers of purient what-if prostitute films everywhere.

With some 260 films screening over one short week, the TIFF truly aims to have something for everyone, even if realty and harlotry don’t arouse. In addition to honoring Malcolm McDowell, the fest hails the art of the stuntman on Saturday morning, March 12, at 10:45am. Several unsung heroes of action films will screen clips of their most courageous and outrageous stunts as well as discuss how exactly to flip two cars against each other in a wall of flame and bricks. Or something like that.

Later that day, filmmaker Orson Welles receives laudatory examination at 7:30pm with a screening of F for Fake to be followed by a presentation by Welles scholar Joseph McBride and former Welles cameraman Gary Graver.

Wrapping up the special programming, director Sam Peckinpah is honored on Sunday, March 13, at 3pm with a showing of Sam Peckinpah’s West: Legacy of a Hollywood Renegade.

For complete and dizzying details on the TIFF, visit www.tiburonfilmfestival.com or call 415.381.4123.

–Gretchen Giles

From the March 9-15, 2005 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.