As a decorated astronaut, Russell “Rusty” Schweickart can forgive a bit of artistic license taken with the science in some space movies. But when he sees it taken to extremes, he says, it can shape public perception, which can also shape government action—and that is a dangerous prospect.

“When you’re talking about something that potentially deals with real possible events, such as asteroid impacts on the earth, then those misunderstandings can be really harmful, frankly,” says the Sonoma resident, who piloted the lunar module in the 1969 Apollo 9 mission.

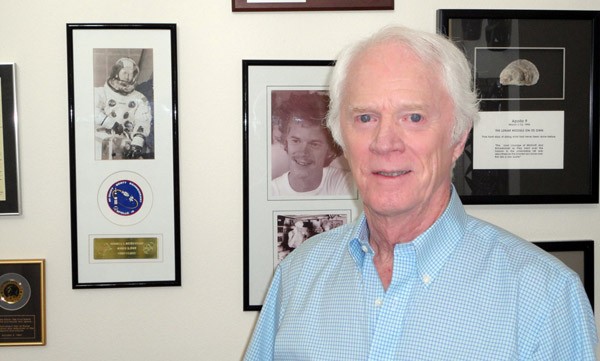

Schweickart’s career includes degrees from MIT and service as a jet pilot in the Air Force before starting with NASA. During the Apollo 9 mission, he was the first to test the Apollo lunar module, which was later used by the first men to land on the moon. He saved the Skylab space station from failure in 1973, and that year was honored with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal and the NASA Exceptional Service Medal.

Though Schweickart is mostly retired these days, he gives a 90-minute illustrated lecture at the Rafael Film Center in San Rafael on April 22 to explain why the science in Hollywood blockbusters like Armageddon and Deep Impact is wrong and, furthermore, why that can be dangerous.

“There’s a lot of embedded misunderstanding that has to be overcome when you’re dealing with a real threat and something that can be done about it by society,” Schweickart says.

Currently, there are plenty of real threats—401 near-Earth asteroids, or NEAs, that we know of today. Of those, the one with the greatest chance of hitting this planet, named AG5, has a one in 500 chance of doing do. Schweickart likens it to the odds of getting in a car accident in the next three weeks. It’s predicted to hit on Feb. 5, 2040, Schweickart says, and we will know for sure by 2023 when it comes closer to Earth. If at that point it passes through a small region in space—a “keyhole”—then it’s all but certain the asteroid will hit the planet on its next trip to Earth, in 2040.

Twenty-eight years may seem like plenty of time to plan for such an occurrence, and it is, but funding has to be allocated beginning in the next few years. The organizations with which Schweickart has been involved in his post-NASA career, including the NASA Advisory Council Ad-Hoc Task Force on Planetary Defense, are dedicated in part to this very problem.

But defending the planet isn’t just about raising money. There are multiple fights in Schweickart’s battle. A project to deflect an asteroid may only cost about $1 billion (paltry when considering other recent government expenditures). But if an NEA were to hit Earth, where would it land? Who would be most affected, and who would be responsible for preventing it? Or, as Schweickart asks, “Whose money? Whose taxpayers?”

He does not doubt at all that it will be possible to deflect an asteroid, from a technological standpoint, by the time it is deemed necessary. One foundation he headed for about 10 years was the B612 Foundation, which is striving, among other goals, to develop and deploy an infrared telescope into solar orbit to search for asteroids.

But society itself may be the bigger obstacle. “The geopolitical issues are, in many ways, much tougher than the technical ones,” he says.

[page]

The United States, which has for decades been a leader in space technology, has been deflecting the issue. There is nothing in NASA’s charter about public safety, and that’s precisely what deflecting an asteroid is all about. With budgets slashed in recent months, it’s not likely more funding will become available within the agency, so money would have to be reassigned.

“There is no tax dollar that is not competed for ferociously,” says Schweickart. “And this is a new kid on the block; it’s something that happens once every several hundred years, and the public doesn’t really understand it. So why should NASA get into a losing battle?”

These are topics likely to be touched on at the talk in San Rafael, interspersed with clips of Bruce Willis and friends trying to blow up an asteroid by burying a nuclear bomb within it, thereby saving planet Earth. It’s an unusual program on its own, let alone one led by the Apollo 9 astronaut known for, among many other accomplishments, taking the first untethered space walk.

The program is part of the Rafael’s “Science on Screen” series, sponsored by two nonprofit groups, which present programs like this across the country. This is the third program of this type at the Smith Rafael Film Center this year, says director of programming Richard Peterson. “It’s a nice thing for us to do something different and something thoughtful like that.” He hopes there will be more programs like this coming this year.

“Films are, by and large, for entertainment,” Schweickart says. “There’s certainly no obligation in film to legitimately portray science. At the same time, film is such a powerful medium that it miscommunicates science to a lot of people, and that presents a very serious problem for science in the sense of people misunderstanding—because of film, in some instances—the reality of the world.”

This could lead to disbelief of government officials, Schweickart cautions, and belief in conspiracy theories of hidden or untrue information. Films he discusses include Meteor, Melancholia, Deep Impact and Armageddon. He won’t go into Hollywood films about astronauts (although he does refer to The Right Stuff as “pure poppycock”).

Asteroids hitting the earth are not uncommon. “We get hit about a million times a night,” says Schweickart. Most of them burn up in the atmosphere, leaving a bright tail, which we call shooting stars. But larger NEAs could make it through with devastating results. If AG5 were to hit, the impact would have more power than 900 of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima.

“[In general] nobody ever thinks about it because it’s supposedly so far away from us,” says Peterson. “But I’m glad to know that are people thinking about it.”