You know the drill. You go to a store, maybe Forever 21 or Target, only to be confronted with a hundred different T-shirts, in every shape and color. It seems so easy. Pick out a shirt, plunk down $10, take it home, wear it a few times, and when the threads start unraveling, toss it out and buy another one.

Recent tragedies at Bangladesh clothing factories? Chinese rivers overflowing with toxic runoff from industrial garment factories? You push these images out of your mind as you leave the store, even while knowing that somewhere in the Third World, there are real environmental and human costs to your new cheap T-shirt.

Rebecca Burgess didn’t push it out of her mind. Instead, she envisioned an alternative, and now heads a national network of localized farmers, textile makers and clothing producers who sell clothes not only made entirely in the United States, from sheep shearing to sweater knitting, but in one’s own local region.

Burgess calls it Fibershed. Just about everybody else calls it an idea whose time has come.

Or, if you will, a time that has come and gone. Just 23 years ago, in 1990, 50 percent of our clothing was made in the United States. Today, according to Elizabeth Cline, author of Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion, that figure stands at about 2 percent.

Fibershed’s very beginnings were borne of such awareness. Burgess had understood the true cost of a cheap T-shirt from years of working with textiles, and in 2010, she put her beliefs about ethical fashion into action, making a personal pledge to wear a wardrobe whose dyes, fibers and labor were sourced from no more than 150 miles from the project’s base.

“I was committed to using local labor, locally farmed materials and locally grown dyes,” explains Burgess, who recently moved from San Geronimo to Petaluma. The project proved to be an “unbelievable endeavor,” she says, if only for the sheer amount of work it took to build a functional and wearable locally sourced wardrobe—all the way down to her underwear.

“The most challenging aspect was getting the clothes,” says the 35-year-old natural dye expert, weaver and educator. “We don’t have a lot of people that know how to make something that fits. Just finding a garment that I could wear functionally and appear semi-normal was hard.” So she reached out to artisans and farmers, building a wardrobe one step at a time.

Burgess still wears the sweaters, skirts and other items created for her by an all-volunteer labor force three years ago. And just like in the old days, before Americans had access to 100 million new pieces of clothing each year—12.7 million tons of which are thrown away—Burgess spends part of each week mending and repairing those clothes to extend their life.

The inspiration to grow into something bigger arose as Burgess wondered how to harness the community built around her project. How could she keep together the community of designers and farmers, and how could she democratize the process, making it accessible to everyone?

Working with her brother and a friend—and a budget of nothing—she launched the Fibershed Marketplace, an online consortium of clothing, kits, yarn and raw fiber from a variety of producers. What started as a personal endeavor soon grew into a nonprofit movement that’s spreading across the nation; Fibershed affiliates have sprung up in Vermont, North Carolina, Utah, Los Angeles and internationally in England and Canada, all united by the goal of creating livelihoods around a garment’s lifecycle, from soil to skin.

The way that Fibershed works is simple. A knitter in Santa Rosa might procure skeins of organic Merino wool from sheep raised by Sally Fox, a weaver and rancher dedicated to a sustainable approach to agriculture at her Capay Valley ranch. That knitter would take the yarn, create a pattern, knit a sweater, and then sell it to, say, a client over the hill in Forestville.

“We wanted to treat it as a place where the community could have access to one another,” she adds. “If someone in Berkeley didn’t want to drive to Napa for the yarn, the farmer could institutionalize the process of getting the yarn out the door.”

This is clothing without the toxic runoff, the pesticides, the incredible dependence on fossil fuels, the unbounded dyes that wash off onto the skin and into waterways, and the horrific deaths of Bangladeshi garment workers feeding the insatiable American demand for cheap clothing.

While the price tag for certain items might seem exorbitant to some—Fibershed sells a coat that costs over $1,000—there are entry points for everyone. “If they can’t afford a Fibershed item, they can make it themselves with the kits,” says Burgess. “We can teach them how to knit. We can teach them how to dye. We can provide them with seeds to start their own dye garden, and we can provide training to learn how to do these things. Someone might say, ‘I don’t want to buy a $200 shirt, but I want to take sewing lessons from the artisan who made the shirt.'”

[page]

Once those people learn to knit, dye and sew their own coat, the true-cost price tag for labor and materials that go into Fibershed’s handmade clothing starts to make more sense.

For those who can’t afford the kits, or the time commitment of learning how to knit (a reality that Burgess readily acknowledges), there are other ways to help beat the exploitative cheap-clothing system. Burgess recommends shopping at thrift stores and buying clothes made from natural fibers—100 percent wool or 100 percent cotton is best.

“Plastic, acrylic and polyester blends are extremely toxic when washed,” she says. “Microfibers have been getting through municipal water treatment systems and out into rivers, bays and oceans.” A 2011 University College Dublin study revealed that during an average wash, one piece of clothing might shed up to 1,900 fibers—microplastics that are polluting beaches worldwide.

It’s facts like these that push Burgess to think in a long-term, visionary fashion about Fibershed’s future.

“The harvesting, the processing, through to the sale—all of that, to me, should be inspiring,” says Burgess. “This isn’t just a product. It’s a way of life. It’s not like you’re just buying a shirt. We’re creating a whole new way of societal functioning.”

For more, see www.fibershed.com.—Leilani Clark

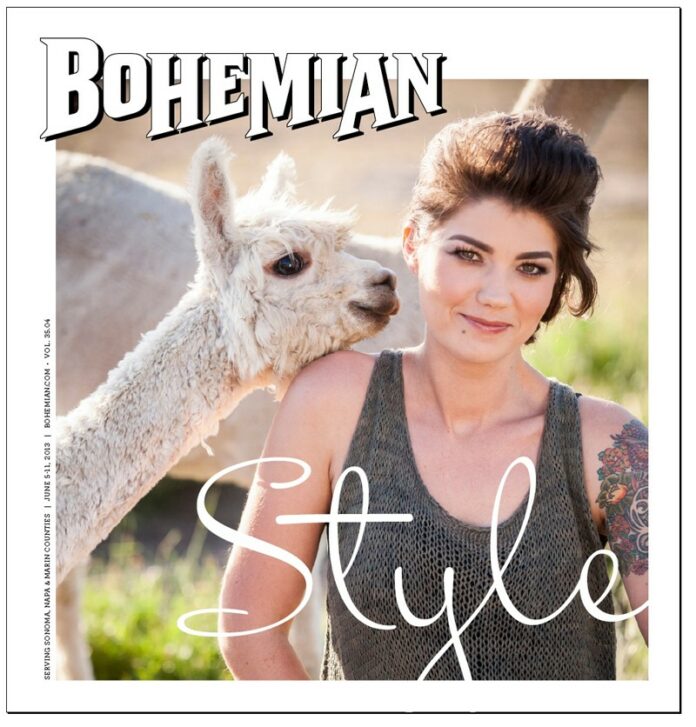

SHEAR DELIGHT TWIRL RANCH, NAPA

An afternoon at Twirl Ranch—the 2,000-acre Napa ranch where Mary Pettis-Sarley and her husband raise sheep, angora goats, cattle, llamas and even alpacas—is an invitation into jolly chaos. After graduating from UC Berkeley with a degree in textile design and spending a few years teaching, Pettis-Sarley moved to the ranch in 1979 to embrace “cowboying” in the wilds of Northern California. Now she spends her time among the animals and plants that provide the materials for her fiber work.

On a Wednesday afternoon, Pettis-Sarley welcomes me into her upstairs studio, her blue eyes and green shirt under denim overalls as bright as the sky outside, and begins bringing out skein after skein of the naturally dyed yarn that’s sold in the Fibershed Marketplace.

“I just have fun,” says Pettis-Sarley, explaining the process behind colors like “thistle” and “onion.” “It’s all a game,” she adds with a laugh, an attitude obvious in her approach to pretty much everything on the ranch, including her animals. With names like Tidbit, Noodle, Mrs. Sprout and Peanut Butter, the sheep and goats sound like cast members from Yo Gabba Gabba. Seventeen dogs run happily across the property, acting as guardians from mountain lions and coyotes.

Up on a ridge above the house, we’re greeted by curious, sweet-faced alpacas—they were “rehomed” to the ranch nearly two years ago—and freshly sheared sheep of all sizes. Pettis-Sarley shows me to the shearing room, where I feel three raw alpaca fleeces. Incredibly soft and lustrous, they are surely the material for the dreamiest of future Fibershed sweaters. It’s in this same space that she cleans and washes the fleece, and then transfers it outside where it dries in the sun before heading to the Yolo Wool Mill to be processed into yarn.

[page]

Walking toward the garden, we pass cast-iron cauldrons sitting over an outdoor stove. “I use those pots for the natural dyes,” says Pettis-Sarley. “I’m just going through the whole plant base of this property. I started with the worst weeds first. It ended up being fabulous.” Overgrown kale from the garden gets thrown into the pot, producing a muted, buttery white color. Eucalyptus from the cow pasture has ended in yarns of red, light green and yellow, depending on the variety. Euphorbia, a plant that looks straight out of a Dr. Seuss book, creates an entrancing, bright mustard-green.

“At the end of the day, I just want to play,” Pettis-Sarley says, standing in the garden over the land that she stewards—glimmering pond, sloping, green valley and all. “I don’t dream that I’m going to get rich, but I dream that I’m going to have a really good time.”

Twirl yarn is available at Knitterly in Petaluma, and can be purchased online at Fibershed.—Leilani Clark

SPUN BY HAND BLACK MOUNTAIN WEAVERS, PT. REYES STATION

Black Mountain Weavers was founded in Point Reyes Station 25 years ago as a co-op for clothing makers, but for the past 10 years, Marlie de Swart has run it with a hyperlocal bent. Of its 30 or so members, five actively participate in running the storefront, and four are handspinners, including de Swart herself. “Handspun yarn is very rare,” she says excitedly, clutching a skein of her own soft, fluffy, undyed yarn. “Because it takes so much work, it’s not always lucrative to sell.”

And yet Black Mountain’s handspun yarn draws knitters from miles around, she says, surely in part because of de Swart’s emphasis on locale. Her skeins are marked with the farm where the wool was sourced—always within 150 miles of the store (most are within 20). “The carbon footprint is virtually zero,” she says, drawing a comparison to fabric from China.

Transportation isn’t the only impact on the earth; in China, wool is heaped into machines the size of her entire store, and excess material is simply burned off into the atmosphere. Chemical dyes run off into waterways, which then seep into the ground or carry out to the ocean. In contrast, de Swart spins yarn on a wheel in her home, and she and fellow co-op members use natural dyes like indigo (plant) or cochineal (insect).

It takes de Swart about two to three hours to make a skein of yarn, not including soaking the wool overnight three times. From there, it takes about two to three days to knit a sweater, and that’s making good time; she’s been doing it her whole life. Her mother was a spinner and knitter in her native Holland, and de Swart moved to California to attend school in Los Angeles about 35 years ago (she still has a slight accent), met the man who became her husband and moved north soon after.

[page]

Feeling good about minimizing one’s impact is great, and the sweaters de Swart knits are incredibly soft and beautiful. (Even if you managed to find something that feels as good inside and out for $265 on the top floor of Nordstrom, it still wouldn’t be hand-made with organic materials.) It’s not just de Swart’s crafts that catch attention in her tiny store on the bustling street, either. Fingerless mittens knitted with angora rabbit fur are in stock, as well as beautiful scarves made to last a lifetime, unique shirts from tightly knitted fabric and even hats made from dog fur. (Dog fur items are usually made by request from pet owners, who bring in their own “wool.”)

The only place to get these handmade items is at de Swart’s store, though a limited number of items are available online through Fibershed. Black Mountain itself does not have an online store, explains de Swart, for one simple reason: “We can’t make it fast enough.”

Black Mountain Weavers, 11245 Main St., Pt. Reyes Station. 415.663.9130.—Nicolas Grizzle

THE ABCs OF CLOTHES HIJK, SEBASTOPOL

Heidi Iverson became a clothier almost by accident. “I make dolls for a living, it’s my day job,” she says inside her small studio that sits among towering trees in west Sonoma County. But an epiphany came while working in a yarn store: the university-trained ceramicist and sculptor realized that yarn is a raw material just like clay. “I thought, I’m a sculptor, I can build clothes,” she says.

HIJK, the hyperlocal clothing line Iverson produces with Jen Kida, uses raw materials that are grown, harvested and processed by people she’s met face-to-face. She uses the material to design, sew and dye—in other words, build—clothes. “You give me the yarn, and I will make something amazing with it,” she says.

The clothes are high-quality, and the price reflects both the finished product’s durability and the work put into making it. These aren’t $10 shirts from a big-box store—there’s one from HIJK that retails for $200. But its functionality has a certain style that isn’t readily available from a kiosk in the mall. One design, large and flowing, is almost like a tunic, with pockets perfect for burrowing chilly hands in—thick yet breathable.

Though her clothes are available through Fibershed, Iverson admits that her priorities aren’t solely about making money. “Most of what this is about is building community,” she says. The cotton comes from a producer in the Capay Valley near Sacramento, the indigo dye is handmade in Novato, and the all the clothes are hand-sewn and designed at Iverson’s studio, making the term “hyperlocal” most appropriate.

Iverson, who moved here from Iowa, also makes dye, which is quite an involved process. For instance, she finds oak galls around her studio and grinds them into a fine powder before soaking them in water for 24 hours. Then she adds iron, procured by letting metal scraps sit in jars of water. The length of time they sit determines how much iron will be added to the dye, which influences the final color. This process has been used since ancient Roman times, and it’s much safer for the environment and less wasteful than synthetic dyes. The tradeoff is that it costs about $37 to dye one $130 shirt—and much more, say, for HIJK’s $300 pair of fisherman’s pants.

Instead of buying clothes over and over again, Iverson would like to see people appreciate what they have, and take good care of it. “People used to fix their clothes,” she says. “In most of Europe, that never really went away. But in the U.S., we’re all about cheap and fast. I would like to see the idea of the ‘slow food’ movement for clothes.”

HIJK maintains a Facebook page, and clothing can be purchased online at Fibershed.—Nicolas Grizzle