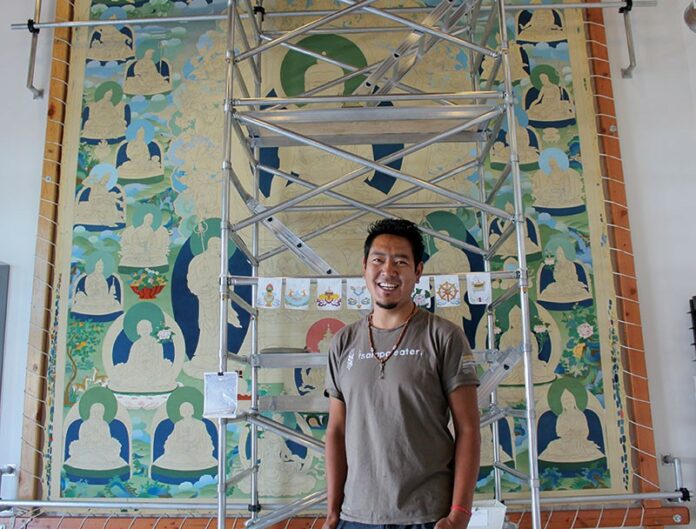

Tashi Dhargyal has big dreams—like, 300-square-foot-canvas dreams. And he’s making one a reality in his Sebastopol art studio.

At the Tibetan Gallery and Studio in Sebastopol’s Barlow retail district, Tibetan-born Dhargyal takes a rare break from painting to watch a World Cup match. Tibet doesn’t have a team in the tournament, but the nation is working on one, he says; it’s a long process—much like the 20-foot-tall traditional Tibetan thangka painting he’s been working on for the past year in the studio, and which will take another four years to complete.

“People pay attention to big things,” he says.

One of the reasons the thangka master is painting on a large canvas, known as a thanbochi, is to raise awareness of the ancient art form. Dhargyal is the first Tibetan artist to paint a thanbochi outside of Tibet. “I want people to see this art and learn about it,” he says.

A thangka is a Buddhist scroll painting usually featuring a Tibetan Buddhist deity or a mandala. There are six stages to creating a thangka. First, an artist creates the grid, which is based on the height of the central figure’s eye. All other parts of the painting are based on increments of this measurement. It took Dhargyal two months to draw his thanbochi with this grid.

Second is shading the sky and grass with mineral-based paint. The kind Dhargyal uses is hand-ground in India. Then comes the painting of solid colors, which is the stage Dhargyal’s massive masterpiece is in now. Next he will shade in all parts, giving the painting a three-dimensional look. After that is outlining the figures.

The final steps are what pushes thangka paintings over the top and distinguishes them from cheap imitations. Solder-like gold is melted with animal glue over steam from tea, then painted on as embellishment. Finally, tiny details are etched into the painting with an agate stone.

A striking facet of thangka paintings is their standard appearance. There are set measurements laid out in books detailing the art form, and the idea of artists signing their names to their work is relatively new. “This is a totally unique composition, but it is completely correct,” Dhargyal says about his thanbochi.

When the thanbochi is completed, it will tour museums before heading to its permanent home in a Tibetan monastery. But in the mean time, it will remain on display in Sebastopol while being being completed.

The Sebastopol transplant learned his craft at the Institute of Tibetan Thangka Art in India, which was founded on a request from the Dalai Lama and which has since been turned into a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the art form. The gallery sells pieces from artists at the school, and does not take a commission on the sales.