In the winter of 2015, a Hong Kong real estate conglomerate purchased the Calistoga Hills Resort, at the northern end of the Napa Valley, for nearly $80 million. Today, mature oaks and conifers cover the 88-acre property, which flanks the eastern slope of the Mayacamas Mountains.

But soon, 8,000 trees will be cut, making way for 110 hotel rooms, 20 luxury homes, 13 estate lots, and a restaurant. Room rates will reportedly start at about $1,000 a night, and the grounds will include amenities like a pool, spas, outdoor showers and individual plunge pools outside select guest rooms.

Following the sale, one of the most expensive in the nation based on the number of rooms planned, commercial broker James Escarzega told a Bay Area real estate journal that the project “will be a game changer for the luxury hotel market in Napa Valley.” That may well be true, but it’s likely not the kind of game changer that many locals want to see.

While the Napa Valley conjures images of idyllic winery estates and luxurious lifestyles, all is not well in wine country. A growing number of residents decry the region’s proliferation of upscale hotels, the wineries that double as event centers and the strain on Napa Valley’s water resources. In the wake of California’s unprecedented drought, the city of Calistoga—like others—has been under mandatory water rationing. “We’re told not to flush our toilets,” says Christina Aranguren, a vocal critic of the proposed resort, whose guests will be under no such restrictions. “I want to know where the water will come from.”

Other new developments will further strain local infrastructure. The 22-acre Silver Rose Resort, across town from the Calistoga Hills Resort, will feature an 84-room hotel and spa, 21 homes, a restaurant, a winery and a six-acre vineyard. Last year, Calistoga’s Indian Springs Resort underwent a $23 million expansion and added 75 new guest rooms to bring its total to 115.

Northeast of the city of Napa, in the rugged hills near Atlas Peak, vineyard developers have proposed removing nearly 23,000 trees to develop 271 acres of vineyards on the 2,300-acre Walt Ranch, which occupies a sensitive watershed above the city’s most pristine reservoir. A decision on the project is expected later this summer. Elsewhere in the valley, about 40 new and modified winery projects, and about 30 new vineyards, await county approval.

“We’re in the middle of a business war,” says St. Helena resident Geoff Ellsworth, a member of Wine and Water Watch, a wine-industry watchdog. “This big corporation is competing against that big corporation, and the collateral damage are the citizens and the flora and fauna.”

The frontlines of Napa’s battles are the hillsides that rise from its narrow valley, which is maxed out with grapes. The situation leaves new or expanding vineyards with only one place to go: up. Though the hills are zoned for agriculture, critics say converting them to vineyards threatens both groundwater and the Napa River, the 55-mile waterway that runs the length of the valley and provides essential habitat to several imperiled species.

“It’s just been a death by a thousand cuts,” says Angwin’s Mike Hackett, organizer behind a contested ballot initiative aimed at reining in hillside vineyard development. “The cumulative impacts of this have not been felt until water became an issue. Now everybody is concerned.”

Napa winegrowers are already subject to some of the toughest hillside- and vineyard-conversion regulations in the state, but enforcement has been inconsistent and new projects keep emerging. The Napa River, notes San Francisco attorney Thomas Lippe, who successfully sued the county in 1999 over hillside-vineyard development, “hasn’t improved. The valley’s groundwater resources are continuing to be stressed. And there’s a continuing loss of biodiversity.” As for county regulators and vineyard developers, he adds, they “just don’t want to deal with it.”

PRESERVING AG

In many respects, the Napa Valley is a national model for land conservation, thanks to the creation of its agricultural preserve, the first in the country, which declared ag and open space the “highest and best use” of most land outside Napa’s towns, and specified agriculture as the area’s only allowable commercial use. Signed in 1968, the ordinance is credited with preventing the type of development that has gobbled so much farmland around the Bay Area. But today, Napa’s challenge is to protect the land from the excesses of what agriculture has become—viticulture, wineries and activities that look more like tourism than agriculture.

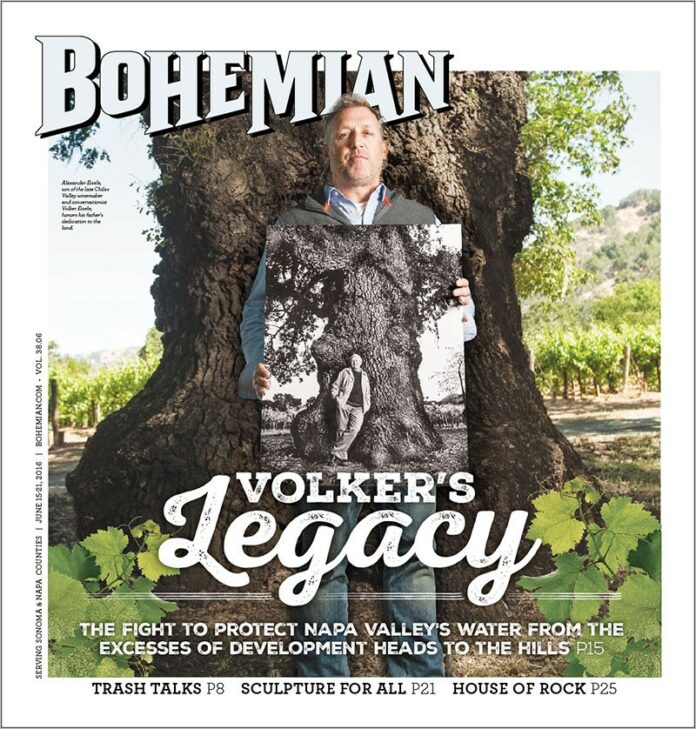

Ironically, one of the prime shapers and advocates of the agricultural preserve warned, in more recent times, that ag’s evolution in the Napa Valley had come to pose a mortal threat to open space and watersheds. That man, Volker Eisele, died in 2015, but not before he identified hillside protection as critical but unfinished business.

A native of Münster, Germany, Eisele was a student at UC Berkeley, when he and his wife, Liesel, began visiting the Napa Valley in the early 1960s. They moved to the Chiles Valley, on the northeast side of the valley, in 1974 and soon began growing grapes on their 400-acre creekside property, which had been planted with vines in the mid-1800s. Farming organically long before the practice entered the mainstream, Eisele ran his Volker Eisele Family Estate out of a cupola-topped winery that had been in operation right up until Prohibition. The family lived in a storybook Victorian home surrounded by a kitchen garden and vineyards that brush up against—but do not climb—steeply rising hills.

Alexander Eisele, Volker’s son and now the manager of the family’s vineyard and winery operations, remembers his father gazing at those hills and asking, “Why is it so beautiful here?” And then Eisele answered himself: “Because the land hasn’t been destroyed. It doesn’t have houses on it.” But Eisele knew that situation might not hold. Fearing that Napa’s fertile farmland might go the way of Santa Clara County’s prune orchards—now known as Silicon Valley—he threw himself into land-conservation efforts that would extend the protections of the ag preserve above the valley floor.

Fifty years ago, when the preserve became law, cattle were the valley’s most valuable agricultural product. Grapes covered only about 12,000 acres. And while many farmers, developers and some winemakers originally considered the preserve overly restrictive, they eventually came to embrace it. Of course, agriculture in the valley has changed radically in the intervening years: today’s cattle operations are economic footnotes compared to the mighty grape.

According to the Napa Valley Vintners trade group, the wine industry and related businesses in 2012 contributed more than

$13 billion to the Napa County economy and provided 46,000 local jobs, making it the largest local industry by far (wine-related tourism brings in more than $1 billion). Today, vines sprawl over 45,000 acres of the valley, which contains approximately 475 wineries. That’s one winery, roughly, every one and a half square miles.

[page]

Napa’s ag preserve originally protected 26,000 acres; today, it’s close to 40,000. The preserve successfully confined residential and urban development to the cities, and it received further protection in 1990, when Eisele, fearing that developers could one day undo these limits, helped to pass an ordinance that requires two-thirds of county voters’ approval for any proposed land-use changes within the preserve.

But in what some locals consider an end-run around this law, called Measure J, the Napa County Board of Supervisors has in recent years made small but critical changes to its general plan, expanding the definition of agriculture and wineries. Now land set aside for ag can host more marketing and sales activities, more food-and-wine dinners, more tours, business events, weddings and even jousting tournaments. The increase in commercial activity adds noise and traffic to rural areas, and it strains the integrity of the preserve.

“We’ve lost the idea of what the ag preserve was,” says Norma Tofanelli, a fourth-generation farmer and the no-nonsense president of the Napa County Farm Bureau. “It was about saving land. It had nothing to do with wineries. [But now] our general plan elevates many urban uses to the same level of agricultural uses. That puts tremendous pressure on ag land, and ultimately we will lose it.”

A RIVER IMPAIRED

Over millennia, the Napa River deposited much of the soil that supports the valley’s vast carpet of vines. But for 40 years, the EPA has classified the waterway as “impaired” due to excessive levels of pathogens, sediment and oxygen-depleting nutrients like nitrates and phosphates, which are discharged from wastewater treatment plants and run off from cattle ranches and vineyards.

The nutrients have spurred excessive algal growth. The algae chokes the river and lowers levels of dissolved oxygen, which is critical for salmon, steelhead trout and other aquatic species. While the river is cleaner than it once was, and some riparian habitat has been restored, the feds still consider its steelhead population threatened and its Chinook salmon endangered. As for the native coho salmon? Extinct since the 1960s.

In recent years, the state has limited three Napa Valley cities from discharging treated wastewater into the Napa River during periods of low base flow, a directive that has helped improve water quality to the point where the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board in 2014 recommended lifting its “impaired” classification. The board is also preparing its first-ever erosion-control rules for agriculture, with a draft environmental impact report expected this summer.

Chris Malan, Napa County’s most ardent environmentalist, has been working to improve the river for decades. Back in the early 2000s, she donned a snorkel and mask to survey creeks in the Napa River watershed for steelhead. In her run for a seat on the Napa County Board of Supervisors this year, she called for a moratorium on new wineries in Napa County. Her platform did not endear her to the wine industry, and she failed to make it past the June 7 primary.

Malan welcomes the state’s new ag-related erosion-control rules, and she gives credit to winegrowers who have worked with the county and state to implement best-management practices on their property. But she strongly opposes delisting the river for nutrients because many of its tributaries are still often choked with algae—a point she made to the water board by presenting video footage of Tulocay Creek, a major tributary to the Napa River.

“You couldn’t see the surface of the water,” Malan says. “It was covered with a green mat of algae for as far as you could see.”

Malan says nutrients from vineyards have gone unregulated and must be brought into compliance. “We have to hit the pause button,” she says. “We’ve got to figure out how to get this right, because it’s just not OK to kill all the fish and have people drink polluted water.”

Arcata-based fisheries biologist Patrick Higgins, who has worked on steelhead and salmon restoration for 20 years, also opposes the water board’s recommendation to delist the river. The ongoing drought, he says, plus illegal water diversions and groundwater pumping, results in less water to dilute pollutants in the river. Water temperatures are rising and fish populations are trying to hang on, he says. “Steelhead trout now inhabit less than 20 percent of their former habitats in the Napa River basin because of flow diminishment,” he wrote in comments to the water board. Those fish, he says, “will go extinct if more decisive action is not taken.”

UNFINISHED BUSINESS

Shortly before he died from a stroke at the age of 77, Eisele shared a glass of wine with Mike Hackett. “We took care of the ag preserve, and now we need to take care of the ag watershed,” Eisele told his friend, referring to the valley hillsides and creeks that drain into the river. “There are more very wealthy people and corporations coming into the valley, and they are not interested in the environment. They are only interested in the expansion of their vineyard properties, and the only place left [for them to go] is in the ag watershed. So watch out. Trees are going to start coming down.”

Hackett remembers this talk with his conservation mentor as a call to action, the impetus for crafting a ballot measure called the Water, Forest and Oak Woodland Protection Initiative. The initiative aims to protect the Napa River watershed by tightening restrictions on deforestation, which reduces a hillside’s ability to store groundwater. Without trees to impede it, rain sheets downhill, erodes stream banks and dumps sediment into the river, degrading fish habitat.

Though supporters gathered more than 6,000 of the 3,900 signatures required to place it on the ballot in November, the county counsel’s office rejected the initiative on a technicality June 10, just four days after the registrar of voters qualified it for the ballot. Attorneys with Shute, Mihaly & Weinberger, the law firm that drafted the initiative, plan to file suit on behalf of its proponents. The firm also drafted and defended appeals to Measure J up to the California Supreme Court.

“We believe that county counsel’s opinion is dead wrong, and that the county acted illegally,” says Robert “Perl” Perlmutter, attorney with Shute, Mihaly & Weinberger. “In our experience, the county’s arguments are those that are typically made by special interest industry groups opposing land-use measures and that the courts have rejected.”

If the initiative is ultimately adopted, developers of new vineyards would be limited to removing no more than 10 percent of oaks from hillside parcels and prohibited from removing most timber within 150 feet of large streams or wetlands. (The state’s proposed erosion-control regulations, now under review, would create best management practices for existing vineyards, while the county’s oak woodland initiative would protect hillsides before they’re converted or replanted to vines.)

History reveals not only the need for such protections, but for better enforcement and significant penalties as well. In 1989, heavy rains sent tons of silt from a new vineyard on Howell Mountain into the Bell Canyon reservoir, fouling the main drinking-water source for St. Helena. In response, the county enacted a first-ever erosion control ordinance.

[page]

But eight years later, the Pahlmeyer winery cleared a hillside without a permit. The incident didn’t cause similar erosion and might have gone unnoticed if the property hadn’t been visible from the hillside home of environmentalist Malan. With the help of the Sierra Club and attorney Lippe, Malan successfully sued the county, Pahlmeyer and other wineries for failing to properly evaluate the environmental impact of vineyard projects. Now all vineyard developments are subject to public review under the powerful California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Still, proponents of the Water, Forest and Oak Woodland Protection Initiative don’t believe that CEQA and county regulations will adequately protect the region’s fragile hillsides from projects like the Walt Ranch. Last April, Joy Eldredge, manager of the Napa Water Division, submitted a withering critique of the project to the county planning department. The environmental impact report, she wrote, failed to demonstrate that the Walt Ranch project won’t adversely affect the Milliken Reservoir, the city’s highest quality water source. As the recession recedes and crowding on the valley floor sends vineyards uphill, she predicted, the quality of Napa’s drinking water will decline as its cost rise.

As evidence of what can go wrong, Eldredge points to the city’s other drinking water supply, the Lake Hennessey reservoir. Unchecked fertilizer runoff from upstream vineyards has increased Hennessey’s phosphate and sulfate levels, which have spurred algal growth. The nutrients have also quadrupled the utility’s cleanup costs, which include treating the water with algaecides and chlorine. Unfortunately, this process can also generate byproducts called trihalomethanes, which have been linked to an increased risk of miscarriage, bladder and rectal cancers.

“Caught between long-term trends of increasingly stringent drinking-water-quality standards on one hand, and increasing county vineyard development approvals on the other,” Eldredge wrote, “the city and its water customers end up bearing the burden of degraded water quality from vineyard development and the need to carry out costly drinking-water-treatment-upgrade projects. The county should prevent the shifting of vineyard development impacts onto the city and its public-drinking-water customers.”

So far, the cost of treating Lake Hennessey water has not been passed on to customers, but if Lake Milliken were to be tainted by vineyard runoff, Eldredge says, rates would rise to cover the cost of new treatment infrastructure.

The Walt Ranch project will, like other hillside vineyards, employ runoff- and erosion-control systems: engineers will dig on-site retention ponds to hold storm water, then pipe that flow to nearby creeks. But Lippe says those erosion control methods, which conform to a county ordinance, are fundamentally flawed. Yes, the ponds and pipes can control erosion on the vineyard property and those directly below it, but when that water shoots offsite from a pipe under high pressure, it undercuts stream banks, erodes streambeds and stirs up sediment. The county, says Lippe, “simply hasn’t adjusted its runoff calculation models to account for how water behaves once you put it into a plastic pipe.”

Walt Ranch developers Kathryn and Craig Hall—who moved to the area from Texas, where Craig made his fortune in real estate and was once a part-owner of the Dallas Cowboys—defend the integrity of their project and their commitment to the environment. Their vineyards boast organic certification, and their St. Helena winery was California’s first to win LEED Gold certification. According to its environmental impact report, the project’s erosion-control system will reduce the current flow of sediment off undeveloped land into Milliken Creek by 43 percent, and level spreaders and rock aprons will disperse and filter storm water ejected from the ranch’s pipe outlets.

“We have a good project,” Mike Reynolds, president of Hall Wines, says. “We are following the directions of the scientists and the county.”

The Halls also promise to remove less than 10 percent of the property’s trees and mitigate those trees’ loss by planting trees elsewhere on the ranch and permanently protecting 551 acres of woodlands.

For Stuart Smith, a vocal property-rights defender who has owned Smith-Madrone Vineyards & Winery, in the western hills above St. Helena, since 1971, the oak woodland initiative is a solution in search of a problem. If passed, he says, it would force him and other growers to apply for costly permits when they expand or replant their vineyards. Napa Valley winegrowers already face plenty of regulation, he says. Any additional requirements will only serve to drive out small, family-owned wineries like his, leaving only big or corporate-backed wineries—the very operations that “gloom-and-doom environmentalists” rail against.

“It’s already happening,” Smith says. “The billionaires are driving the millionaires out.” And if the initiative passes? “My chainsaws are going to be running,” he says. “I’m not going to let these yahoos do this to me.”

Ted Hall, the president and CEO of St. Helena–based Long Meadow Ranch, a winery and diversified farm with 2,500 acres in production in Napa and Humboldt counties, calls the proposed initiative an anti-farming ruse cloaked in environmentalism. No science backs it up, Hall claims, and it could even result in the removal of more non-oak trees and more hillside home development when vineyard planting and other ag uses become too costly and difficult.

Like many businesspeople, Hall (no relation to Kathryn and Craig Hall) prefers voluntary stewardship to top-down regulation. In 2002, he and a coalition of the wine industry, the Napa County Farm Bureau, environmental groups and state and local government initiated a certification program called Fish Friendly Farming, which teaches property owners in the Napa River watershed how to reduce bank erosion and flood damage, improve fish habitat and reduce sedimentation.

While critics say the program, now called Napa Green, allows for certification after harmful grading and tree removal have already taken place, it does teach best practices in sediment control, and program leaders claim it has substantially reduced the flow of nutrients and sediment into the watershed. According to Ted Hall, more than 40 percent of Napa Valley vineyards have been certified under the program.

THE RECKONING

Residents of the Napa Valley have long invoked Volker Eisele’s name with reverence. Because he was a landowner, a winemaker and a member of the Farm Bureau, he moved in many different circles, making allies who helped him shape and promote important conservation legislation. But it’s not clear, now, who has the stature to protect the Napa Valley’s remaining natural areas from the wine juggernaut. Napa Vision 2050—a coalition of more than a dozen civic and environmental groups that advocates for responsible planning—is pushing hard against the status quo.

Many of its members, plus scores of other volunteers, helped collect signatures for the oak woodland initiative. The valley’s wine trade groups have united in opposition to its protections, as has the Farm Bureau.

Whatever the outcome of the battle over the initiative, it seems clear that Napa Valley’s success as a winegrowing and tourism powerhouse has been, as the commercial broker quipped to the media, a game-changer. Exactly how residents reckon with these changes will define the valley in the months and years ahead. It is a reckoning the prescient Volker Eisele saw coming. “That this could change rapidly, to this day, human beings have trouble believing,” he told an oral historian in 2008.

Harmful development, he said, “can happen more or less overnight, if you allow it.”