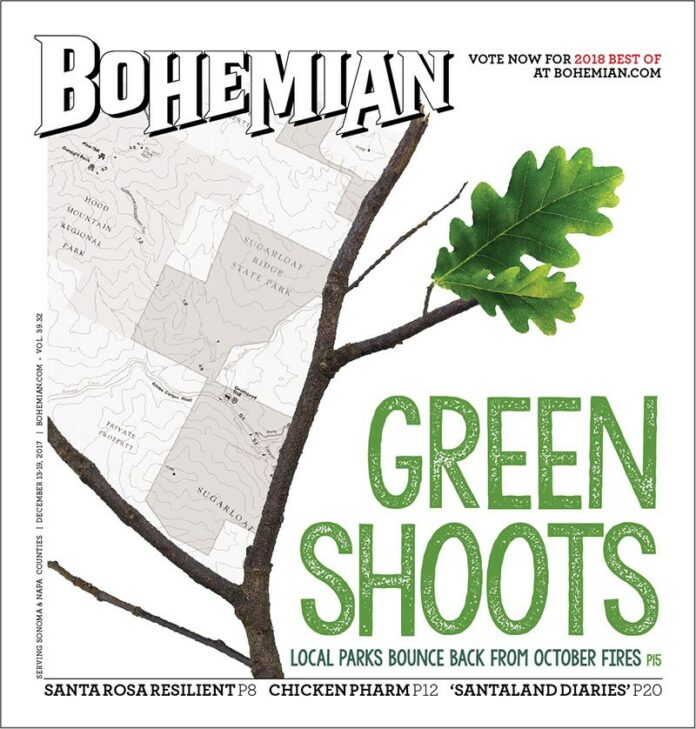

On the map, it looks bad for Sugarloaf Ridge. Eighty percent of the state park was burned in the Nuns fire, whose ragged 52,894-acre boundary all but engulfs Sugarloaf’s 4,020 acres. The park is closed to the public until further notice.

To get a preview of what visitors might expect to see when this beloved local resource for hikers, campers and stargazers is reopened sometime next year, I meet up with a ranger at the park gate for a tour.

Our two-car convoy is soon delayed by a debris-clearing operation in the road. Clad in orange jumpsuits, an inmate work crew supervised by Cal Fire is loading brush and tree limbs into a truck-mounted chipper. While there’s evidence of burning on both sides of the road, mostly grass and understory burned here, and encouraging glimpses of green can be seen on the other side of the forested canyon.

My guide, supervising state park peace officer Robert Pickett, explains that much of the tree-cutting work in this area has been done to clear debris that could flood and wash out the Canyon Trail below.

The truck moves aside, and it’s a marvel to see the kiosk at the park entrance. There’s the visitor center, intact, as well as key facilities in the campground, although fire crept up to the edge. Not a single picnic table burned, according to Pickett.

Further on, Robert Ferguson Observatory still stands under a backdrop of burned chaparral. Colossal, chain-sawed sections of a partially fire-hollowed tree are parked in front of it, plucked from the blighted ravine below the parking lot. Trees like this have been removed if they could endanger buildings and visitors—one among several reasons the park isn’t slated to open soon. “There are still some sketchy trees out there,” says Pickett.

Yet a wooden outhouse in excellent condition is still perched on the edge of the burned area. A bulldozer sits in the meadow, awaiting an unknown task—perhaps restoring dozer cuts made in the land as firebreaks, and now threatening erosion. Beyond, a swath of straw covers a dozer line that’s headed toward the summit of Bald Mountain.

The tour continues some distance past the Saturn sign, on the Meadow Trail’s “planet walk,” but stops short of Uranus; the bridge across the creek is more than half burnt out. Mostly made of steel, it will be re-planked.

“See those orange spots?” Pickett points to forested slopes of Sugarloaf Ridge to the south. “Those aren’t necessarily trees going through their fall colors.” Picket explains that the fire jumped from here to there along the ridge, leaving a lot of green canopy. It’s altogether not bad for 80 percent burned—but is this area, indeed, part of that 80 percent?

‘I like to use the term ‘experienced fire,'” says Melanie Parker, natural resource manager and deputy director at Sonoma County Regional Parks. “Because people expect total devastation, but most of the acres in our parks—and, really, most of the acres in those two fires [Tubbs and Nuns]—were low to moderate severity in nature’s perspective.”

Regional parks affected by the fires include the small, multi-use Tom Schopflin Fields, Crane Creek and part of Tolay Lake, as well as Shiloh Ranch and Hood Mountain.

Parker’s getting two kinds of phone calls from people: some want to know if the parks are devastated, while others are concerned that the county will do harm through its restoration efforts.

After the 1964 Hanley fire, non-native grasses were seeded and problematic pine trees planted. “Our policy is definitely not to seed grass in burned areas,” Parker reports, “with some very limited exceptions.” Where plants and seeds have been entirely scraped away by bulldozers, the county is seeding native grasses. “You’ll see all the parks regenerating quickly, because they’re adapted to this.”

Asked about the visual impact of dozer lines, Parker pauses. “The good news is, our parks helped stop the fires from burning more of our communities.”

Aggressive dozer lines helped to stop fire short of Windsor held the line for Rincon Valley. “The bad news is, yeah, they’re super-impactful,” says Parker. A photo provided by Regional Parks shows a wide swath cut through Hood Mountain’s pygmy forest.

“Mindful that we don’t want people to do damage to the parks, or the parks to do damage to the people,” says Parker, Shiloh Ranch should be opened by Christmas, and a partial opening of Hood Mountain can be expected on the Los Alamos Road side later in December. “We’re just turning the corner right now,” she says. “We have been in fire-response mode and erosion-control mode. We know that many people want to get out and volunteer.”

Rather than planting trees, volunteers may be tasked with protecting naturally regenerating baby oaks to prevent grazing by deer. Another idea is monitoring stations: hikers could snap photos with smart phones at certain locations, and be part of a post-wildfire monitoring system.

Asked if people who love certain parks and trails might be moved to tears when they see them, Parker says no. “I think, quite the contrary, people are going to be inspired by what they find in the parks,” she continues. “I think it’s going to be a source of healing for everyone.”

The 237-acre Sonoma Valley Regional Park opened over the Thanksgiving holiday weekend. The parking area is in good condition—perhaps thanks to their good neighbor, a Cal Fire station. Nominally, this park is 100 percent burned, but a stroll down the paved Valley of the Moon trail finds a carpet of green shoots pushing through a light layer of char. Incredibly, every memorial park bench—rest easy, John, Annette and Arlene—remains in place with nary a scorch mark, while Zoe the happy dog’s picnic table now also hosts a solemn memorial in stone to victims of the fires.

Higher up on the Woodland Star trail, sporadic stumps indicate where a fire crew located a hollow that continued to smolder, and lacy trails of ash spill down the hill where the occasional tree burned hot. This trail also offers one of the few available views of the blackened, eastern portion of Trione-Annadel State Park.

Trione-Annadel is also now open to the west of Lake Ilsanjo, roughly outlining the area of the park that did not burn. The fire-affected area to the east remains closed, and includes the 30-acre freshwater Ledson Marsh, home to a number of special status species like the California red-legged frog; Sonoma alopecurusa, a federally endangered plant, and the western pond turtle, listed as a California species of special concern. One such turtle got lucky after a string of misfortunes, says Cyndy Shafer, senior environmental scientist for California State Parks Bay Area District.

The fire burned the wood covering an old well in this area. While park staff were evaluating the site, they discovered that a turtle had managed to survive the fire, only to fall into the 12-foot-deep pit. “State park staff were able to rescue it,” Shafer reports.

“At a population level, wildlife are adapted to fire,” Shafer notes. “You also see, following fire, some unique, fleeting habitat—dead trees provide habit that is really rich for woodpeckers, other birds and insects.”

The state currently has no plans for seeding, not even on the dozer lines. Shafer says that experience after the 2013 Morgan fire in Mount Diablo State Park proved instructive. “Once we had done work to repair and re-contour those dozer lines and restore the land form,” says Shafer, “we saw that vegetation comes back really well.”

When I cycled to the summit of several years ago, I noted some odd-looking plants growing in the burns. Were those weeds, or invasives? Probably not, Shafer tells me. “What you often get is fire-following plants. They are fleeting in abundance. They show up on the landscape every 60 years after a wildfire.”

Shafer says that often, impressive spring blooms of wildflowers also follow a burn. “It’s something that people

can look forward to, and feel hopeful and optimistic about their parks.”