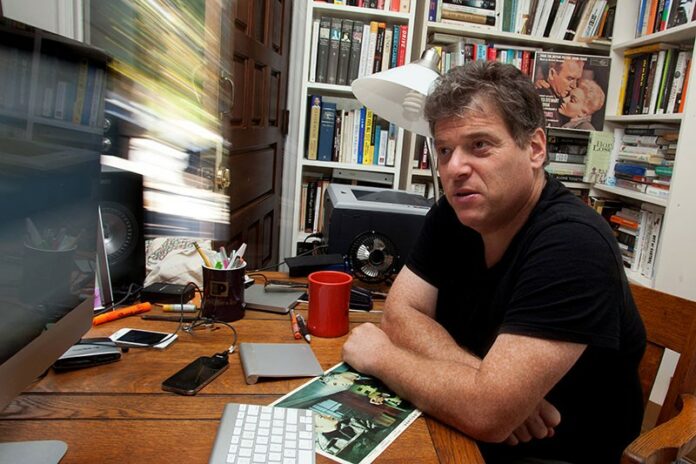

Santa Rosa author, speaker and entrepreneur Andrew Keen isn’t interested in becoming your Facebook “friend.” He’s interested in saving your digital soul.

A CNN columnist and host of the TechCrunch chat show Keen On, the British-born transplant brandishes a mordant, simmering wit that blooms to full ire when discussing issues of personal privacy in the age of Web 3.0. In his most recent book, Digital Vertigo: How Today’s Online Social Revolution Is Dividing, Diminishing, and Disorienting Us, Keen contends that Facebook and its ilk aren’t the utopias of interpersonal transparency much ballyhooed by their makers, but rather a kind of exhibitionistic self-enslavement that precludes privacy and solitude, which Keen believes are prerequisite to living fully developed lives.

The notion that “social” media makes us less social isn’t entirely a unique one, and Keen is the first to admit it. Thus, to frame his ideas, he interweaves themes from the classic film Vertigo.

“It’s a remix of Hitchcock’s movie, which is about a man who fell in love with a rich blonde who turned out to be a rather poor brunette who was also a murderess. I fear that with social media, the blonde is, of course, Facebook—we’ve all fallen in love with it—but just as in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, the ‘everyman’ Jimmy Stewart got ‘dressed up’ and taken advantage of,” he says drolly. “We’ve all been taken advantage of. We’ve all been turned into the product.”

As a read, Digital Vertigo is a galloping, reference-jammed, personal essay that explores privacy in the age of social and indicts everyone from a 19th-century prison architect to a certain bottle-blonde along the way.

“When you use Facebook, you are the product and they’re profiting from you,” observes Keen. “If you want to know what Facebook’s business model is, look in the mirror. You’re paying for Facebook and none of that revenue is coming back to you.”

In Digital Vertigo, Keen points to how the culture of “sharing” advocated by Mark Zuckerberg and other social-media titans is tantamount to a wet dream for intelligence agencies. We willingly reveal tons of private data, our present locations, what we had for lunch and other miscellany comprising our lives, that, when aggregated, produces an accurate and predictive portrait of who are, who we know and what (and even who) we’re doing.

“We should be paying for our content on the internet,” Keen argues, “and until we figure that out—and consumers grow up and understand that they need to pay for online content—they’re going to continue to be abused and exploited by data-mining companies like Facebook and Google.”

Keen, 53, grew up in North London, studying history at the University of London. After moving to the United States, he earned a master’s degree in political science from UC Berkeley. Still keeping a house in Berkeley, he moved to a modest 1939 bungalow in the JC area of Santa Rosa in 2010 to be with his two children. On a recent morning, they fiddle around on iPads in the living room, while Keen, in shorts and a plain black T-shirt, offers tea and discusses his place in Silicon Valley.

“I see my role in the Dawkins-Hitchens tradition,” says Keen. “Some of these people take themselves so seriously.”

Naturally, Keen is not without his critics. As Sebastopol-based tech publisher and open-source advocate Tim O’Reilly opined in the 2008 documentary The Truth According to Wikipedia, “I think [Keen] was just pure and simple looking for an angle, to create some controversy and sell a book. I don’t think there’s any substance whatever to his rants.”

Keen is aware of his reputation, and in fact seems to relish it. On his Twitter profile he describes himself as “the Anti Christ of Silicon Valley.”

As for O’Reilly, “I think he’s a little oversensitive,” says Keen. “I respect him, politically. And I think O’Reilly is a decent guy. I think he’s a good person. But his response to The Cult of the Amateur was such an outrage—that I was only doing it to make money or get attention.”

[page]

Cult of the Amateur: How Today’s Internet Is Killing Our Culture, Keen’s 2007 bestseller that’s since been translated into 15 different languages, begins with Keen’s epiphany at O’Reilly’s FOO Camp, in 2004, while listening to a bunch of wealthy Silicon Valley types talk incessantly and religiously about “democratization.” Media, entertainment, business, government—nearly everything, went the rallying cry, would be “democratized” by what O’Reilly had famously christened Web 2.0.

“The more that was said that weekend, the less I wanted to express myself,” Keen writes in the book’s introduction. “As the din of narcissism swelled, I became increasingly silent. And thus began my rebellion against Silicon Valley.” (O’Reilly declined comment when contacted for this story.)

Current targets of Keen’s scorn and ridicule run the gamut from Sean Parker and his lavish wedding ceremony in Big Sur (“I’m interested in this idea of Silicon Valley trying to engineer serendipity”) to Google Glass, which Keen sees as the beginning of an inevitable migration of personal computing off of our desktops and out of our pockets and onto—and eventually into—our bodies.

Sitting near the television at Keen’s house is a DVD, rented from the video store down the street, of Minority Report. Steven Spielberg’s 2002 film foresaw graphical user interfaces, gesture-based navigation and ultra-thin transparent screens, technological advances now part of modern life. But one prediction in the film eerily rings far truer than the others: when Tom Cruise walks through the city, retinal scans pick up his individual information, and targeted advertising suddenly appears, keyed to his personal data.

This seemed intrusive and insidious just 11 years ago. In Keen’s view, it’s something in which we now willingly participate. Except it’s not called a retinal scan—it’s called a “status update.”

“We go on the internet and we use these services, and we’re not willing to pay for them. We use Google and Facebook without really understanding that their business model is acquiring our data so that they can sell more and more advertising,” says Keen. “If you’re not paying for your content, check your pockets, because you’re being taken advantage of.”

Keen’s sentiment echoes that of his friend Nicholas Carr (author of The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains), who argues that Facebook and its ilk represents a form of “digital sharecropping.”

“One of the fundamental economic characteristics of

Web 2.0 is the distribution of production into the hands of the many and the concentration of the economic rewards into the hands of the few,” wrote Carr all the way back in 2006. “It’s a sharecropping system, but the sharecroppers are generally happy, because their interest lies in self-expression or socializing, not in making money.”

Keen concurs. “We’re all back in the antebellum South here in terms of working in the fields, guaranteeing massive profit for a small group of people who are laughing all the way to the bank.”

What is the cultural mechanism that brought us to this place of full disclosures, and what pan-global personality tick is it exploiting?

“We’re all desperate to express ourselves. We all think we have something interesting to say about ourselves, so we feel we have almost a moral or aesthetic obligation to go on Facebook and tell the world what we’re having for breakfast, what we’re wearing or, all too often, what we’re not wearing,” says Keen.

“I don’t think we can blame the social networks; we have to blame ourselves,” adds Keen. “We’ve fallen in love with ourselves, we think that our narrative is interesting, and actually, it’s incredibly boring to everyone except ourselves and the advertisers who are profiting from us,” he continues.

[page]

Keen doesn’t identify himself as entirely anti-Facebook. “When a grandmother uses it to connect to her grandchild or when we catch up with friends from school or college we haven’t seen in years—those aren’t bad things,” says Keen, who, noting he owns an iPhone, iPad, Macbook Air, iMac and Canon 5DII, insists that he’s not a Luddite, either.

But call him an elitist, as Stephen Colbert did on

The Colbert Report in 2007, and Keen will wholeheartedly agree.

“I’m unashamedly elitist in the sense that I believe there’s only a small group of people that are talented and hardworking enough to create great books, movies and songs, and the vast majority of us are much better off actually consuming that stuff, paying for it and enabling a viable cultural economy than wasting our time blogging or putting our worthless photos, songs or movies up,” Keen says.

Since the majority of social networks originate in the United States, it’s suggested there might be something endemic to the American psyche, some kind of hybrid of our can-do spirit and guarantee of free speech that causes us to believe that since we can share our amateur efforts, we should share our amateur efforts.

“We’ve fallen under this sort of uber-democratic illusion that everyone has something interesting to say,” asserts Keen, “and they don’t.”

For many, Keen’s acerbic manner and proclivity for blunt statements (e.g., “Most of the stuff on the internet is either biased or bad”) might disqualify him as a spokesperson for the world of working media professionals. In reality, Keen is among a media professional’s fiercest allies. In Cult of the Amateur, Keen essentially argues that people should leave media-making to the pros.

Of course, as a maker of content, online and off, Keen has a vested interest in professionals being compensated for their work. It’s a difficult point to counter, especially when one considers that consumers seem happy to pay for everything in the world except online content. (Keen applauds institutions like The New Yorker and the New York Times, which have paywalls around their content, and asserts that more creators should do the same.)

Why we should start paying for online content is best illustrated by paying attention to the ads in a browser’s sidebar. You might have noticed that after a Google search for a specific item, advertisements for the item seem to follow you around the internet for days afterward. This is an example of how your ostensibly private online behavior is being used to both market you and market to you. This, asserts Keen, is part of the price of free content.

For those with paranoid dispositions, privacy is merely the gate fee. What other personal costs might be levied? Consider the fact that college admissions offices routinely review the social media accounts of new applicants to gauge their suitability for campus life. Then, of course, there are the recent revelations of the NSA’s social snooping, courtesy of Edward Snowden, which link companies like Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Yahoo to the agency’s PRISM program.

“It did in some ways predict this giant panopticon where everything we do on the internet is being watched,” says Keen of Cult of the Amateur. “I didn’t predict it was the NSA, but the relationship between the NSA and some of these tech companies is very dodgy, too, and very troubling.”

Dodgy as it may be, we’re caught in a bit of cultural shift, one in which Keen’s suggested remedy for our privacy concerns—simply paying for content—isn’t necessarily the fix. The fact is, Facebook and Google don’t want you to pay for content, at least not with real dollars. A fair amount of social engineering has transpired in the past decade to bring “radical transparency” into the personal sphere. And that is vastly more valuable to data-driven entities than your 99 cent download.

What Americans should really stop doing, says Keen, is giving away their data in a misguided effort toward posterity.

“What we need to teach the internet is how to forget. At the moment, the internet is lacking a human quality—all it knows is how to remember. Forgetting is much more human than remembering.”

And for Keen, he’ll know humanity has triumphed and reclaimed its privacy when someday we ask, “Remember when the internet was free?”

–

Andrew Keen appears with over 70 media and tech professionals speaking at C2SV, a three-day conference of tech and music running Sept. 26–29 in San Jose. Along with tech discussions and presentations, more than 60 bands perform in a lineup headlined by Iggy and the Stooges. For details, see

www.c2sv.com.

Andrew Keen is at ajkeen.com and tweets as @ajkeen.

Daedalus Howell is at dhowell.com and tweets as @daedalushowell.

Bohemian editor Gabe Meline (@gmeline) contributed reporting to this piece.