At the Santa Rosa Health Center in Roseland, 50 percent of Dr. Patricia Kulawiak’s adolescent patients are obese. “There is an epidemic of diabetes in this area,” Kulawiak tells me over the phone, “and since good, healthy food is expensive, poverty severely limits your options.”

Thanks to the Work Horse Organic Agriculture (WHOA) Farm, dozens of these families receive bags of fresh, organic produce every week—for free.

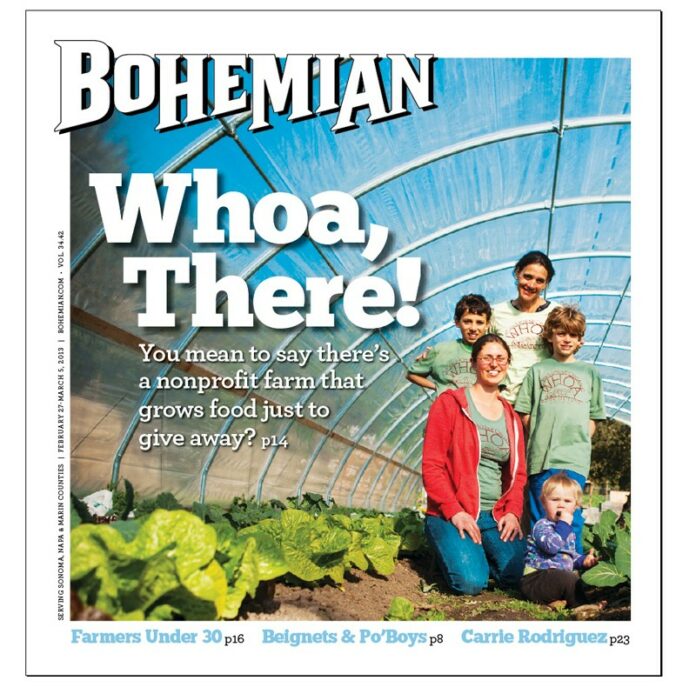

Started two years ago by Eddie and Wendy Gelsman, WHOA Farm’s motto is “The best food money can’t buy,” a tidy summation of their mission to provide fresh, organically grown food to those who can’t afford it. “It’s not a crime to be poor,” says Eddie. “Everyone has the right to eat well.”

Located on 16 acres on Petaluma Hill Road, WHOA Farm began with six months’ worth of nonprofit application paperwork and a few raised beds, which the Gelsmans cultivated themselves. In January of 2012, they hired young farmers Balyn and Elli Rose to live on the property and run the farm, which, as the name indicates, is one of the few in the area that harnesses the power of draft horses to plow the fields. “Horses,” says Wendy, “are the ultimate piece of the sustainability puzzle.”

Even though they were just a few weeks from having their first child, and even though they had never before worked with draft horses, the offer to work on the farm “was an opportunity we just couldn’t pass up,” says Elli, who met Balyn in an agro-ecology class at UC Santa Cruz, where they both graduated in environmental studies.

“They are two highly educated and highly skilled agriculturalists,” Eddie says of the couple, who prior to WHOA ran a farm and CSA program called Wild Rose Ranch for four years.

Together with Dan Evans, the only other full-time WHOA Farm employee, the Roses grew and donated 15,000 pounds of organic produce, 876 baskets of strawberries and 556 dozen eggs to health clinics and food banks across Sonoma County last year. (According to Cathryn Couch of the Ceres Community Project, WHOA provided $14,000 worth of food to their organization alone.)

While plenty of farms and supermarkets donate their leftover produce once it is no longer marketable, WHOA is unique in its practice of growing food specifically to give away. Produce is harvested in the morning and delivered that same afternoon in order to “give people food with the highest nutritional value,” says Eddie.

Anyone who’s ever inherited a surplus of fennel or radicchio understands that fresh produce is a wonderful thing—as long as you know what to do with it. Which is why education is at the heart of WHOA’s mission. “We are committed to giving away food responsibly,” explains Wendy, “which means that we want people to be comfortable with the produce and understand the nutritional value of what they’re eating.”

[page]

To that end, health centers in Santa Rosa and West County offer nutrition classes (some taught by Ceres) in which patients learn how to turn things like kale and rutabaga into healthy, delicious meals. All who attend—many of them at-risk, uninsured and low-income—are given a bag filled with WHOA produce to take home.

Ever ambitious, the Gelsmans want to do even more. “Our goal is to be able to give away teams of draft horses to young farmers,” says Eddie, whose plans for WHOA also include hosting educational workshops and internships. Of course, nothing is possible without funding. In addition to private donations, grants, fundraisers, monthly volunteer days, and an outreach booth at the Santa Rosa farmers market—where customers receive a jar of Elli’s sauerkraut or fruit preserves for a ten-dollar donation—WHOA is also cultivating creative financial solutions.

The Gelsmans are leasing the Crane family’s 11-acre vineyard (conveniently situated smack-dab in the middle of WHOA’s property), and with the generous help of winemakers Guy and Judy Davis, will soon make WHOA Pinot Noir. Beginning in the fall of 2014, they hope to sell 600 to 800 cases annually, which could provide over 50 percent of WHOA’s operating budget.

On a recent Friday afternoon, I walk around the farm with Elli and 11-month-old Olivia, who mimicked the sound of the hens clucking outside their mobile chicken coop; every couple of days they move it to fresh, new grass. Using expert Doc Hammill’s “gentle horsemanship” approach, Balyn, who calls this his “ideal job,” harnesses Chip and Mark, whose shiny blonde manes and tails belie their dude-like monikers.

The Gelsmans’ vision is evident in the green fields of oat hay shimmering in the winter sunlight. After conditioning the soil for spring planting, the hay will be harvested and fed to the horses, who will then plow the fields where onions, lettuce and parsley sprouts will soon take root. And come September, a patient at the Santa Rosa Health Center will discover the spicy kick of mustard greens or the surprising sweetness of a just-picked carrot.

“By honoring the people who are used to getting the leftovers,” Dr. Kulawiak says, “WHOA is working to dismantle health disparities. They are helping people make changes that will last for generations.”