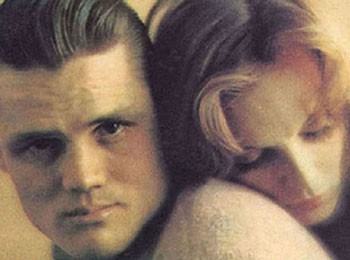

Fine Young Cannibal: Jazz hero Chet Baker, whose breathy vocals and sexy trumpet were good enough to anger Miles Davis, led a life of artistry and tragedy.

Prince of Cool

New box set spotlights Chet Baker’s lush life

By Greg Cahill

You can gauge the significance of a modern jazz player by the number of times his or her name pops up in Miles Davis’ contentious 1989 autobiography, Miles, and by the vociferousness of the attack.

By that standard, trumpeter and singer Chet Baker was a giant.

Blessed with chiseled cheeks and matinee-idol good looks, an ultra-smooth tone and a dreamy voice indicating he was definitely in touch with his feminine side, Baker became the poster boy of the West Coast jazz scene, a group of mostly white musicians that made post-bebop jazz popular with college audiences.

Davis had collaborated with some of the West Coast jazz guys, notably saxophonists Gerry Mulligan and Lee Konitz (both of whom appeared on Davis’ landmark 1949 recording Birth of the Cool), and he goes fairly easy on them in his book, but he spares no venom for Baker.

“A lot of white critics kept talking about all these white jazz musicians, imitators of us, like they was some great motherfuckers and everything . . . like they was gods or something,” Davis wrote. “What bothered me more than anything was that all the critics were starting to talk about Chet Baker . . . like he was the second coming of Christ. And him sounding just like me, worse than me even while I was a terrible junkie.”

Needless to say, Davis wasn’t too pleased when Down Beat magazine named the upstart Baker as Best Trumpet Player of 1953.

A new three-CD box set, Chet Baker: Prince of Cool (Blue Note/Pacific Jazz), highlights Baker’s talents and shows that the 1953 accolade was well-deserved. Culled from sessions recorded for the Pacific Jazz label between 1952 and ’57, the set breaks no new ground; all of these recordings have been available elsewhere, and the 1994 four-CD compilation Chet Baker: The Pacific Jazz Years remains the definitive collection of his work from this period. Still, this newly remastered anthology, neatly divided into three categories, should serve as an accessible introduction to acolytes and offers an easy way for cognoscenti to get Chet-at-a-glance, with or without the vocals.

Disc one (“Chet Sings”) focuses on those dreamy vocal numbers; disc two (“Chet Plays”) zeroes in on his trumpet-led instrumentals; and disc three (“Chet and Friends”) features the trumpeter in band settings collaborating with such jazz luminaries as Mulligan, Art Pepper, Stan Getz and Shelly Manne.

Liner note contributor Ted Gioia, author of West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California, 1945-1960, writes, “[Baker’s] Pacific Jazz recordings . . . feature some of the defining moments of [his] career. From misty-eyed vocals to in-the-groove workouts alongside tenorist Phil Urso and pianist Bobby Timmons, serving as counterfoil to various other ‘name’ players . . . Baker made his mark as one of the defining jazz artists to emerge in the 1950s.”

Baker easily personified the icy romanticism that marked the cool-jazz scene. He also was one of history’s most tragic jazz figures.

Born Chesney Henry Baker Jr. in Oklahoma, Baker grew up in L.A. and served two hitches in the Army. While stationed in the Presidio, he began frequenting San Francisco’s jazz clubs.

After a second discharge in 1952, he rose quickly to prominence, with his big break coming that spring when sax legend Charlie Parker hired him for a few West Coast dates. That summer, Baker joined the Gerry Mulligan Quartet and recorded his first Pacific Jazz sessions. He was just 23.

He made his acting debut in 1955 in the film Hell’s Horizon. His lush life also became the inspiration for the fictionalized 1960 Hollywood film All the Fine Young Cannibals, with Robert Wagner portraying Chad Bixby, the fast-living jazz musician based on Baker.

During the 1960s, the musician lived up to his image, developing a heroin habit and landing in jail. In 1966 he was beaten on the streets of San Francisco, an event that may or may not have contributed to the loss of his front teeth (Baker had neglected his dental hygiene for years).

In 1968, he began wearing dentures, which are a difficult adaptation for a trumpet player who depends on his teeth to shape his embouchure. Baker’s touring and recording schedule diminished, and by the early ’70s he had stopped playing altogether.

In 1973 he staged a comeback, resumed recording, though sporadically, and toured mostly in Europe. Elvis Costello hired him to perform the mournful trumpet solo on his classic “Shipbuilding” in 1983, introducing Baker to a new generation of jazz fans.

In 1987 photographer Bruce Weber began shooting a film documentary about Baker. Let’s Get Lost, released the following year, won widespread acclaim and would have ensured Baker’s return to prominence, but just weeks before its release, the trumpet player toppled to his death from an Amsterdam hotel window after ingesting heroin and cocaine. Fans still debate whether he fell accidentally, committed suicide or was pushed.

Prince of Cool affirms that at least for a few glorious years in the mid- to late ’50s, Chet Baker stood on top of the jazz world, and there’s no disputing that fact.

From the January 5-11, 2005 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.