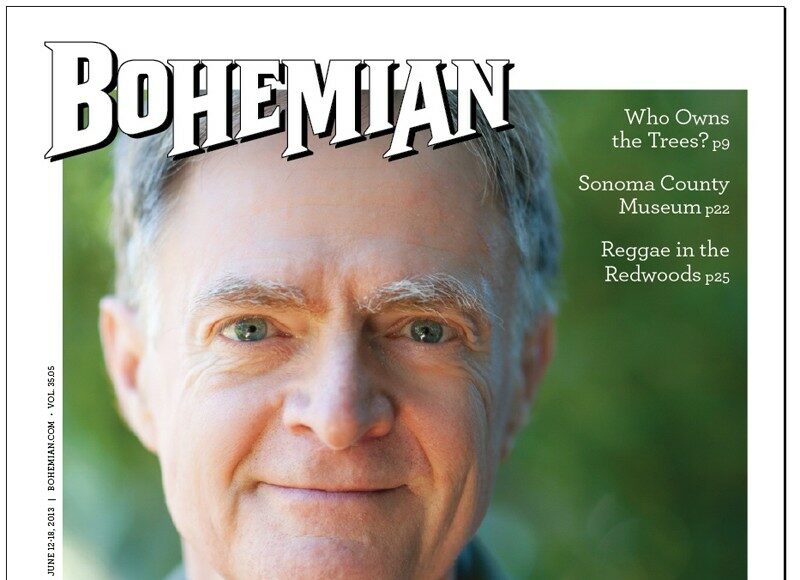

Richard Heinberg is surprisingly chipper for a man who, if projections by the U.S. government and global-energy analysts are to be believed, might just have seen the basis for his career virtually debunked.

The Post Carbon Institute senior fellow smiles easily in the art- and book-filled living room of the Santa Rosa home he shares with his wife, Janet, even as he talks about the implications of a fracking-fueled petro-boom from North Dakota to Pennsylvania that’s got U.S. energy executives crowing about abundant fossil-fuel-derived energy to last the next century or two.

It’s a claim that directly flouts the concept of peak oil—the point at which global petroleum production goes into terminal decline—and Heinberg’s assertion that growth (as we know it) is headed into irreversible decline.

Wearing a blue-checked Oxford shirt, jeans and house slippers, Heinberg’s relaxed demeanor could be due to time spent among the fruit trees and chickens in his backyard permaculture paradise. Maybe it’s the two hours of violin the self-described “violin junkie” plays each day. Or it could be the possible ace in his pocket—a February 2013 report by retired geo-scientist J. David Hughes and published by the Post Carbon Institute which claims to debunk the possibility that unconventional fuels might turn the United States into an energy-independent petro-state.

The report forms the foundation for Heinberg’s new book, Snake Oil: How the Fracking Industry’s False Promise of Plenty Imperils Our Future, out on July 1.

“We’re really being sold a bill of goods,” Heinberg says, handing over a copy of the Hughes report, “Drill, Baby, Drill: Can Unconventional Fuels Usher in a New Era of Energy Abundance?” Using data provided by a Texas company called DI Desktop, which analyzed production data for 65,000 fracked wells from 31 shale plays, the report examines natural gas as a commodity. According to their findings, production rates at many of these sites are already in decline. Operators then must drill more and more to keep overall production steady, and with that comes increased energy needs, making the whole endeavor more expensive.

Aside from fracking, methane hydrates—the trapped natural gas molecules currently being scouted by Japanese research vessels and found in abundance on the sea floor—have been heralded as the next frontier. The speculative fossil-fuel goldmine forms the basis for Charles C. Mann’s May 2013 cover story for The Atlantic with the headline that declared, with the impact of a lightning storm in summer, “We Will Never Run Out of Oil.”

But then there’s the problem of net energy, Heinberg points out. “The vast majority of those resources we won’t burn for economic reasons,” Heinberg says, “because it just costs too much—not only investment capital, but it costs too much energy to get the stuff out of the ground to use it.” It’s a concept defined as EROEI—energy return on energy invested.

Heinberg’s previous seven books, including The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality and Peak Everything: Waking Up to the Century of Declines, came out on traditional publishers. But for Snake Oil, the Post Carbon Institute turned to Kickstarter, raising $15,000 for self-publishing costs.

“The subject is so hot we just wanted to get it out as soon as we could,” Heinberg says. Snake Oil takes on what he calls dangerous oil-industry claims that the U.S. has enough tight oil to provide a decade’s worth of cheap, abundant gas. “Now, suddenly, with a bump in production of U.S. oil and gas, everyone is talking about, well, gee, isn’t this great?” Heinberg says. “And so the conversation about how to get off fossil fuels has just been put on the back burner.”

[page]

It’s true. In his 2012 State of the Union speech, President Obama estimated that there’s enough gas “down there” to fuel the country for nearly 100 years. Daniel Yergin, considered one of the world’s foremost authorities on global energy, told Radio Free Europe on June 2 that the shale gas windfall “means that there is a rebalancing of world oil production that is now occurring, and it points to greater stability in the oil market and not that fear of shortage and peak oil that was causing so much difficulties for the global economy half a decade ago.”

Even George Monbiot, The Guardian‘s environmental columnist, conceded defeat after years of writing about peak oil. “There is enough oil in the ground to deep-fry the lot of us, and no obvious means to prevail on governments and industry to leave it in the ground,” he wrote in July 2012.

Heinberg, on the other hand, appears unshaken. The increase isn’t something we should get used to, he says, pointing to the data uncovered by the Hughes report. What we should be doing, rather than looking for ways to extend and continue our fossil-fuel dependent lifestyle, is investing time and energy into building renewables, while there’s still the energy available to build wind turbines and solar panels.

Heinberg is also a big supporter of the Sonoma Clean Power initiative, not only because it will allow the county the chance to get out from the grip of the PG&E monopoly, but because of its potential to function as a bridge to the other side: “It can speed up the rate at which we transition to renewables here in Sonoma County,” he adds.

Heinberg’s obsession with energy began in 1972, at the age of 21, after reading The Limits to Growth, a controversial, statistics-driven study that projected possible scenarios for the 21st century based on world population, industrialization, pollution, food production and resource depletion. Dismissed as doomsday prophesying by the economics world, it triggered others to seriously consider resource depletion.

The book sent the young writer into a period of thinking the apocalypse was just around the corner. He spent the ensuing years studying—acting as personal assistant to mythologist Immanuel Velikovsky and writing books that would help him sort out why “one species would be driving the whole world toward the precipice.”

Heinberg’s first two books focused on mythology and summer solstice rituals around the world. It wasn’t until the late ’90s that he began to understand that the history of energy was the biggest story around.

[page]

“As time has gone on and as I’ve studied the data, I’ve come to realize that it’s more of a process, not just falling off the cliff,” he explains.

Part of the process, for those not involved in the higher echelons of government and society where policy decisions are decided, is to live consciously. Heinberg and his wife Janet have started that process at the suburban Santa Rosa home they purchased 12 years ago.

“We wanted to show that this could be done,” says Heinberg, as we tour the backyard. The backyard is a dreamy oasis—and one that you’d never guess existed from the street. Herb spirals bloom with thyme, rosemary and lemon balm; a vegetable garden overflows with greens; solar panels generate power, and a water catchment system harvests rain. Apple, pear plum and pomegranate trees shade the yard. In one corner, potatoes sprout in burlap sacks stuffed with straw. What Heinberg is most excited about, though, are Buffy, Scarlet and Azalea, his three chickens. The “pets,” he calls them, cluck around our feet, scrambling for insects and bits of scraps. Call it country living, with easy access to a future SMART train station and the amenities of the city.

It’s also in close proximity to Loveland Violin Shop in downtown. “I’m a bit obsessed with it, as my wife would tell you,” he says with a laugh.

Living here, with the garden, the chickens and the violins, Heinberg looks to be a man in his element, negotiating a careful balance between the heavy realization that life as we know it is headed for irrevocable change, and the simple joy of everyday living.

If humans look honestly at the crisis at hand, begin sharing, using less, being nice to each other, there’s no reason we can’t have a perfectly acceptable future, he tells me. But that means facing facts. To make a true transition, the technical piece would be relatively easy, he explains; it involves building lots of solar and wind, prioritizing electric rail and redesigning cites for walking and bicycling. Heinberg mentions his admiration of the Transition Town movement, which started in the United Kingdom and uses permaculture concepts to build resilience in communities to weather gracefully the coming economic and environmental upheavals.

Of most concern is whether the “fossil fuel” industry is successful in making people believe that there’s enough oil and gas to keep us going for another century, in the style in which we’ve become accustomed, he emphasizes. The oil boom in North Dakota (and elsewhere) is going to be short-lived, but it’s bought us some time—a few short years—to get to work on renewables.

“If we use that time—maybe it’s five or 10 years—to really invest in renewable energy and conservation, than so much the better,” he says. “But if we just take those five or 10 years and delay what we ultimately have to do anyway, at the end we’ll be in a much worse position than we already are.”