Malice in Gangland

Photos by Janet Orsi

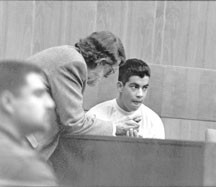

The accused: Tomas Galvan, 16, is charged with attempting to murder a Windsor youth in a gang-related assault. Galvan is the youngest person ever tried as an adult in the Sonoma County.

Two Windsor teens prepare to go on trial as adults for the brutal beating of a local youth. Fear rises over gangbangin’ in suburbia

By Dylan Bennett

HE’S A SKINNY KID, nearly six feet tall. His father says he likes skiing and basketball, a “recreation kind of guy”–a rebellious teenager who doesn’t like school. His mother says he has a “heart of gold” and loves kids and animals. Sixteen-year-old Dylan Katz got his braces off in May, just a week before moving from Concord to Windsor. Six days later he lay battered on the pavement near a shiny new elementary school right around the corner from rows of crispy-clean housing developments in the county’s newest town.

Twelve hours later, Katz’s mother, Donna Meza, could barely identify him as he lay in Santa Rosa Community Hospital. “I can’t think of anything more horrible,” she says. “He looked like a freak. His head was about the size of two basketballs. You couldn’t even see his eyes, they were all closed in. You couldn’t see his eyelashes, that’s how swollen his head was.”

Today, after two months in a coma, Katz once again can communicate with his father, John, though he is still hospitalized and unable to walk. Raise one finger for yes, two for no. As a result of the brutal beating, Katz suffered severe brain damage. He breathes on a respirator and has an intravenous-feeding tube to his stomach. “Do you know why you are here?” Katz’s father asks him. In response, Dylan scrawls, almost illegibly, on a white board with a blue pen: “I got the shit beat out of me.”

On the night of May 2, two rowdy youths allegedly punched and kicked and stomped him. The teens were accompanied by three others in a car driving on the west side of Windsor. One of his assailants reportedly boasted of jumping on Katz’s head like a trampoline, leaving the attacker’s basketball shoes soaked in blood. Tomas Galvan, then 15, and Jose Madrid, 17, Katz’s alleged attackers, the story goes, are members of Varrio Westside Windsor, a local youth gang.

GANGS. The word strikes fear into the heart of middle-class suburbia. Kids gone bad. It raises images of stereotyped baggy clothing, intimidating rap music, and confrontational, sometimes violent behavior. The victimization of Katz appears random and senseless, but what is the context to this heinous crime?

Nine out of 10 acts of gang violence are against other gangs, rarely spilling over into society at large. Dylan Katz was caught in that 10 percent of bloody spillover. In the Katz case, two teen-aged boys of Mexican ancestry stand accused of attempted murder, robbery, and most notably, of being gangsters, which could mean additional years in jail if found guilty. Both have pled not guilty. Both will stand trial as adults. If convicted, they could spend 35years in prison. Their trial begins Sept. 20.

Galvan, 16, is the youngest person ever to be tried as an adult in Sonoma County. His father Tomas Sr., says his teenaged son is wrongly accused. “We feel that Tom is being made an example by the media and the system,” he said after a recent court hearing. “Our son is wrongly identified as a gang member and has been described as being vicious and animal-like. It as if it is a crime to be a Mexican in this courtroom. There have been cold-blooded murders by juveniles who have not received such cold-blooded treatment such as my son has been given. I speculate that it is because a Mexican boy supposedly assaulted a white kid.”

Katz’s mother says: “It’s not even animal-like. It’s worse.”

Police officials say there are 20 certified criminal street gangs in Sonoma County–twice as many as just two years ago–and many more that are uncertified, but clearly dangerous. “They may start out throwing rocks, but inevitably they move to guns,” observes Petaluma police Sgt. John Turner.

Beyond the confines of simple cops-and-robbers, understanding the sudden rise of gangs in Sonoma County means tackling complex issues of criminal justice, class conflict, and racial antagonism. All the local gangs have a Mexican cultural orientation, law enforcement officials say, although membership crosses racial lines. Certified gangs must meet stringent legal criteria of organization and felonious intent, all set by the state Attorney General’s Office.

In Santa Rosa, police anti-gang efforts focus on neighborhoods around Apple Valley Lane, Papago Court, West Ninth Street, and South Park. That’s where the gangs are and that’s where many of the poor people are. That’s also where many people of color are. To pragmatically disrupt gang crime, police teams patrol these areas heavily. The result often is an adversarial cat-and-mouse game between blue uniforms and brown-skinned people.

Gang crime, focused mostly in communities along the Highway 101 corridor, falls in the middle of the range of public mayhem and includes drug dealing, burglary, and fighting–and sometimes murder. Heroin and home-cooked bootleg methamphetamine, on a continued rampage locally, are readily available in gangland. Sgt. Turner–the burly cop who heads Petaluma’s anti-gang unit–says local gangs like to steal firearms for resale and personal firepower. Citizens with firearms are a favorite target for those robberies, he adds.

Traditionally, the landscape of Mexican gangs in California is divided between two rival camps. There are “Norteños,” the Northerners, second- or third-generation Mexicans who wear the color red and flaunt the number 14. And there are “Sureños,” the Southerners, first-generation or immigrant Mexicans who wear blue and tout the number 13. “They kill each other left and right,” says Meza. Historically, Fresno–in California’s Central Valley–was the line of demarcation, but distinctions of colors and north-south geography are not strictly followed anymore.

Driving around the back streets of East Petaluma, Turner draws a crude picture of an umbrella on his notepad. The umbrella’s skin, he explains, is the overall identity of the Bloods or the Crips or, in this case, Norteños and Sureños. Under that skin, local gangs–or “sets”–are the ribs of the umbrella that support the skin. They claim local territory and signify themselves with red or blue. But they may have little or no contact with red and blue gangs in other cities.

Detectives say individual gang rosters in the county range from about a dozen to over a 100. Average age of the members falls between 13 and 24. Beyond that, police say, gang members either get out of the gang at a young age, go to jail, or die. A curious exception: Local police blotters include one motorcycle gang with a 70-year-old member, possibly a holdover from the heyday of the Hell’s Angels, whose notorious deceased founder Sonny Barger grew up in Roseland on the outskirts of Santa Rosa.

In recent years, local law enforcement officials have confiscated semi-automatic pistols, ranging from .22 to .45 caliber, plus rifles and shotguns, and once in a photograph they identified gang members with an AK-47 and an AR-15 assault rifle.

The letter of the law is specific. A group is officially designated a criminal street gang when it has a common name, identifying sign, or symbol; when there’s evidence that a primary activity is the willful promotion of felony crime; when participants engage in a pattern of criminal activity; and when the district attorney agrees the group meets the criteria.

The spirit of the law is confusing. Is being in a gang a crime? “Yes,” says Sheriff’s Detective Dennis Smiley. “No,” says David Dunn, a gang prosecutor at the Sonoma County District Attorney’s Office.

Sort of, not really.

This discrepancy suggests the ambiguities involved in stopping gangs. Crime is crime, and committing a crime as a member of a gang is two crimes. But if a person is in a certified gang and doesn’t commit a crime, is he a criminal? No.

“They can be in a street gang as long as they don’t violate any laws,” says Dunn. “That’s not a violation. But then it wouldn’t be a street gang. There are people who are believed to be members of street gangs, but as long as the so-called street gang doesn’t engage in any criminal behavior, then you can’t prosecute them for being in a street gang.”

Dunn, an 18-year veteran of the District Attorney’s Office, has prosecuted four cases this year in which he sought enhanced sentencing for gang status. One involved three youthful members of Varrio South Park in Santa Rosa, all charged with assault. They pled guilty and got probation, so the sentencing enhancements had no effect. A second assault case went to a jury and resulted in an acquittal. In the third, Dunn charged a gang member with intimidating a witness. At the preliminary hearing, the judge ruled there was insufficient evidence. The defendant was released.

The fourth case involves Dylan Katz and his assailants.

In this “pretty damn complicated” legal environment, the fate of Katz’s alleged assailants will be determined. Those are the words of Madrid’s appointed defense attorney, Joe Stogner, who says there is a danger that in the pubic fervor over this case his client will be convicted of a crime he did not commit. Stogner says specific intent to kill will be difficult to prove and claims the gang element of the trial will not withstand jury scrutiny.

Prosecutor Dunn agrees gang crime is hard to prove. “Most crimes committed by gang members are done under circumstances where we are not able to prove that there is any other gang member actually involved in the crime,” he says. “And, similarly, we [often] are not able to prove that the motivation for the crime was to further a gang’s activity.

“You can pass all kinds of laws, but if you can’t prove that the crime comes within the law, then the law is not going to be any help.”

Still, Dunn says, he will press for sentence enhancements based on the reported conversation between the alleged assailants and the victim in which Katz supposedly was asked about his “colors,” the evidence of a red Stanford University sweatshirt stolen as a trophy, and gang symbols drawn on a deodorant can and stereo speakers found in the defendants’ homes.

“This is not a gang case,” says Stogner. “It’s a case about young people without stable families and with a lot of pent-up anger who release it on impulse with no intent. My client: his mother was brutally murdered in 1987 when he was between 8 and 10 years old. And his father not too long thereafter went to prison, after my client found out that his mother’s body had been thrown near a creek. My client had been basically in unrelenting emotional pain for many years with no family structure, with no guidance, with no one to help him out.

“It’s very difficult to explain the background of someone accused of a crime because people assume you’re trying to justify that behavior, but it’s a huge factor.”

The designation of Varrio Westside Windsor exists only to identify those residents that lived on the west side prior to the recent development boom, Stogner says. The alleged gang is a loosely affiliated group that doesn’t qualify as a criminal street gang, he insists.

It’s true that the Varrio Westside Windsor is not a certified street gang. But according to local westside kids, their associates are plentiful and specialize mostly in graffiti and physical intimidation. At Healdsburg High School, where the accused teens attended classes, Principal Bob Harbaugh says he has 50-gallon trash bags filled with confiscated red and blue, extra-long, webbed belts with brass belt buckles, scarves, and other gang-related paraphernalia. He estimates that about 5 percent of the student body is involved in a relatively immature gang culture–enough to disrupt the learning process with fights and posturing.

Throughout contested gang areas in the county, graffiti found on walls, large trucks, and fences testify to an emotional war of words, symbols, and turf marking. Typically, gang initials and numerals are crossed out or mocked by follow-up graffiti rivals who paint their own scheme. Gang-prevention work stresses that such graffiti be quickly painted over, but many remain a long time.

At the Sonoma County Jail, classification Sgt. Ray Fleming, responsible for housing inmates, says 10 percent of the nearly 1,000 inmates are certified gang members. When Fleming counts “associates and affiliates,” that jumps to four or five out of 10. He separates Norteños and Sureños to prevent violence, and this segregation puts a strain on the number of beds available for the general population.

Sureños, Fleming adds, accept only Hispanics and whites, while the Norteños accept people of any ancestry. The parent organization of the Sureños is the Mexican Mafia, according to Fleming. Of the two groups, the latter cause the most discipline problems, he claims, always maintaining a tough face, an aversion to authority, and resistance to jail rules and policies.

Struggling to understand: Nancy Orvalle, left, and Donna Galvan, mother of one of the accused.

According to Nancy Ovalle, executive director of the Sonoma County Peace and Justice Center in Santa Rosa, the brown-on-white violence in Windsor is not a random accident, but has its roots in historical animosity. “People are being pushed out of their neighborhoods, particularly up in Windsor because of the developing bedroom community,” she says. “They want to push out the old Windsorites. I was talking with a household in Windsor a week ago. They are being surrounded by developments on all sides, and there are only the little enclaves left. They are renters. They want to know: Where are they supposed to go after this?”

Many of them have lived in Windsor all their lives and are shaken by the rapid social changes. “It gets into your survival instinct, and when a person’s basic survival–food, shelter, clothing–is threatened, then people are going to react,” she adds. “I don’t advocate violent reaction, although I can see how it could come about. There are roots you can definitely trace it back to. You can only beat a person to death for so long.

“There is no justification for what they [Galvan and Madrid allegedly] did, but you can look at social trends and you can say, ‘Well, you know, it’s not too surprising that something like this happened.’ I don’t think that these boys are vicious animals, given the circumstances of growing up Mexican in Sonoma County. It’s a hard thing to do. It’s a hard place to grow up.”

Violence like the Katz case can happen “like this,” says Chris Castillo, a gang counselor with Petaluma People’s Services. “You are somewhere with the least bit of intention and . . . ” Windsor was developed without a plan for kids, she adds, and the community is beginning to feel the repercussions. “You’ve got all these kids crammed into a small area with no services for them, activities, really valuable activities that interest kids.”

Castillo describes a social and economic split between whites and those “indentured [to] servitude and the white power base.” The historical element behind gang violence, she says, is “huge.”

Others also blame the lack of activities in the town for the rise in youth violence. “I think Windsor is more worried about getting their new Wal-Mart as opposed to taking care of things,” says Dylan’s father. “Maybe if these kids had something to do they wouldn’t be getting ‘jumped into’ gangs. I think a lot of those kids could be saved if there was something for them to do.”

Dylan’s mother agrees: “[Windsor kids] have nothing. [Windsor] did open up a community center here, but it’s all new. And these gangs have been building here for the last five years. [The community is] building a Boys and Girls Club.

“When they have more for kids to do, I think that’ll help.”

Since the assault on Katz, continued gang violence has left at least one person dead in the county and several others injured. A man, apparently a rival gang member in blue, was stabbed in the neck and died near the same street corner where Katz was beaten. In that recent case, youth violence–gang against gang, brown on brown–did not make local headline news.

Being a gang “participant” may or may not be crime, but it’s enough of a reason for police to enter an individual’s name on an international database without arrest, court-presented evidence, or conviction.

The Gang Reporting, Evaluation, and Tracking system holds the names of 960-odd local gang “participants” from throughout the county and provides law enforcement officials with valuable “intelligence” in their anti-gang work. Individuals are called gang participants and put in the GREAT system if they meet one of seven criteria: admission of participation; identification by a “reliable informant”; identification as a person residing in or frequenting a particular gang’s area; use of a style of dress, hand signs, symbols, or tattoos that are gang-related; association with known gang participants; or identification as a participant by known participant.

This year, police entered about 100 new names into the database.

Gathering such information dovetails with the police belief that if a person acts like a gang member, dresses like a gang member, and talks like a gang member, he will almost certainly become one.

That approach is controversial.

Steve Fabian, assistant public defender and vice-chair of the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, says the criteria for entering names into the GREAT system are wrong and poorly followed by police. “If you look at the certification, they don’t distinguish between members and participants,” says Fabian, who has 17 years’ experience as a public defender. “They’re all put in the GREAT system the same. That’s a big, big difference. If you are in danger of becoming a gang member, then you are a gang member [as far as law enforcement officials are concerned]. You are what you are in danger of becoming.

“There’s a big difference,” he adds. “A lot of people dress in the clothes, but they don’t commit the criminal acts. But police are saying: ‘You wear the clothes. As far as we’re concerned, you do [commit the acts].’ And that’s a big difference–a big jump they make.”

Says Assistant District Attorney Dunn: “A number of people who admit to being gang members have never been arrested. It’s kind of surprising that sometimes these people will get arrested, but they will have no criminal record whatsoever. Yet they will be self-identified gang members with all the trappings, tattoos, and everything.”

Recent raids by the federal Immigration and Naturalization Service in Petaluma, Santa Rosa, Rohnert Park, and Windsor were supported with data from the GREAT system, Fabian says. “These people are being taken outside the criminal-justice system. They are being punished for being in the wrong neighborhood because of these crazy gang criteria, which are no criteria at all.”

Fabian suggests that people wrongly entered into the GREAT system will encounter bias and unfair treatment owing to their classification as gang “participants” if ever they do enter the criminal-justice system. “Before they start listing you, it seems like you should do something wrong,” he says. “It’s making you a criminal without having committed a crime.”

Detective Dennis Smiley, a Sheriff’s Department gang expert, says that’s “conjecture” on Fabian’s part. “We list people for what they do, not how they dress.”

IN THE MOVEMENT to keep kids out of gangs, activists say young kids need to be steered away from gangs in junior high school and even earlier. Counselor Castillo says a typical candidate for gang involvement doesn’t have a great life and may suffer from low self-esteem; a lack of friends; violence, drugs, or sexual abuse at home; a lack of food, housing, and clothing. Often they are kids without family structure or family communication. “The family awareness is really critical,” Castillo says. “Parents need to get involved in school. Don’t just leave it for the teachers. It’s also about setting boundaries for kids. Where are they? What are the phone numbers [of their friends]?

“Don’t let them run you.”

Detective Smiley agrees that it’s important for parents to get involved in their kids’ lives and to help them stay away from gangs. “Know where your kids are,” he advises. “Kids aren’t getting the attention they need at home. Gangs take the lead with bored kids. Throw your kid’s closet open. If it’s all red or blue, you’ve got a problem.”

The parents of Jessica Roe have such a problem. Their daughter was found guilty Aug. 28 in Sonoma County Juvenile Court of being an accessory to attempted murder in the Katz case. Once the queen of a high school dance at which Jose Madrid was the king, Roe is one of three youths alleged to have been with Galvan and Madrid when the attack occurred. Afterwards, she aided their escape and concealed their whereabouts and identity from the police.

Roe, 17–with fair skin, dark hair pulled back in a bun, and dressed in a loose-fitting purple T-shirt–sits quietly and teary-eyed as Judge Arnold Rosenfield explains how narrowly she missed incarceration at the California Youth Authority, a system of brutal youth prisons operating at 175 percent capacity. Instead, Roe will likely serve about six months in the local Sierra Youth Center, with rehabilitation, counseling, and possible access to work and school.

In the small, crowded courtroom, a view of the bleak grounds of the Juvenile Justice Center on Pythian Road is visible through the windows, Roe’s mother weeps silently as Rosenfield sternly lectures her daughter about morals and the need to make right decisions.

“What we are talking about,” he tells Roe, “is human dignity, human mistakes, and human spirit. You’ve got a choice to make as to whether you are a human or not.”

From the September 5-11, 1996 issue of the Sonoma Independent

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

© 1996 Metrosa, Inc.