We pedal our bikes through a gray industrial neighborhood in San Rafael, past warehouses, parking lots, shipping containers and auto shops. Vehicles roar by as we stop beside a tree hanging over a chain link fence. Under our feet are the remnants of the year’s crop—splattered figs.

It’s November, and there are no fruits to taste today, but Maria and I have had them before—large black figs filled with sweet raspberry pulp—and today we’ve come for something better: the tree’s wood. With a pair of rose cutters, I take several two-foot branch ends and drop them into my bike pannier.

Turning to my girlfriend, I quip a favorite tagline to outings like these: “We may not have any figs to take home, but at least we have the genes.”

At my home in South Sebastopol, I cut the wood into six-inch sections and stick them into pots of moist garden soil. Within weeks, they’ll sprout roots and leaves—replicate trees being born. Rooting figs is an easy process; cloning for dummies. Eventually, exact genetic copies of the San Rafael tree will be growing in my backyard orchard, along with a few dozen other fig varieties.

People have been doing this same thing for millennia. A native of the Old World, the common fig originated somewhere in the Middle East, and humans have cultivated it since the agricultural crack of daylight. Traders dispersed the species north into the Caspian basin, eastward into Asia and west to Africa and Europe. Figs arrived in North America with the Spaniards, who, along with their guns and cannons, packed along their favorite varieties, and the trees found their way to the West Coast with the missionaries. For many decades thereafter, fig trees grew in the gardens of Catholic mission churches and on small farms.

But Ficus carica has escaped the confines of California’s agriculture industry. Accelerated by birds which eat the fruit and disperse their seeds, figs have gone wild and become a notorious invasive pest. In the Sacramento River valley, they have formed dense thickets along the banks of the river, smothering native plant communities. Conservation groups and agencies have tried with limited success to eradicate figs in several state parks.

But for another community of people, the invasive trees have created a playground for discovery. Driving along rural roads or bushwhacking through riverbed fig jungles, hobbyist fig growers are now tapping this resource for undiscovered treasures. In recent years they have found exceptional edible fruit on wild seedlings growing nowhere else. Propagated from cuttings in home gardens and marketed via online trading platforms, these new, genetically unique varieties have attained star stature and are finding their way into private fig collections nationwide. The Yolo Bypass fig was discovered several years ago in its namesake flood control channel near Sacramento and has become a prized collector’s item on Figbid.com. So have new varieties such as Belmont’s Beauty, found growing along a cliff in the Sierra Nevada foothills; Holy Smokes, first collected from a Santa Barbara churchyard; and a colorful plethora of others from Lake Shasta to San Diego.

Sonoma County permaculture teacher and edible plant collector John Valenzuela discovered a wild fig tree near the Tiburon peninsula while riding a bicycle about 20 years ago. During the next fall fruiting season, he had his first taste of its jet-black figs.

“I was blown away by their beauty, outside and inside, their size, their flavor, and just the miracle of the tree being in that spot—you had to wade across a salty tidal ditch next to the freeway along a fence line,” he recalls. “That was such a magical find.”

Valenzuela began distributing cuttings of the tree, and he keeps potted copies of his own at the Hidden Forest Nursery, where he works. Here, Valenzuela grows about 20 fig varieties.

But Valenzuela’s collection is eclipsed by others. In Napa, Aaron Nelson has about 50 different fig trees. Near Occidental, Gary Pennington has experimented with roughly 200 varieties, sold or discarded many, and now has about 80. A grower near the Delta town of Isleton, perhaps known best by his social media handle “Figaholics,” has an orchard of more than 300 varieties. One Santa Barbara fig hunter, Eric Durtschi, has grown and evaluated roughly 800 varieties, many first collected from wild seedling trees.

Hundreds more collectors, connected via social media, are assembling extensive fig libraries across the continent, from Vancouver Island to Florida, from the Gulf Coast to the Great Lakes. With proper seasonal care, most varieties will produce high-quality edible figs just about anywhere in the Earth’s mid-to-lower latitudes. Fig growers enjoy ripe summer fruits in such boreal regions as British Columbia and even Sweden.

California Fig Hunter

But California is a very special place for fig enthusiasts. That’s because, within the United States, it’s only here that Ficus carica grows wild. This came about through a string of events beginning in the late 19th century, when farmers of the San Joaquin Valley imported a fig from Western Turkey, near Smyrna. A yellow-skinned variety known as the Sari Lop, it was planted in large groves around the Fresno area. After several years, growers observed a disappointing pattern: Each July, their Sari Lop figs swelled to the size of a walnut, then shriveled and dropped without ever ripening.

Through several expeditions to the eastern Mediterranean to investigate local cultivation methods, the United States Department of Agriculture identified and solved the problem: Certain figs—Sari Lop among them—will not ripen unless pollinated by a particular species of wasp, Blastophaga psenes, a miniscule insect native to Western Eurasia. So, the USDA imported the fig wasp to California, as well as the hermaphroditic caprifig trees essential to the insect’s life cycle. The industry promptly took off, the first successful crop of Sari Lop figs hit the market in the summer of 1899, and the variety—renamed locally the Calimyrna—became the state’s signature commercial cultivar alongside the black mission, whose fruits ripen without pollination.

But besides allowing Smyrna-type fig varieties to ripen, the fig wasp does another remarkable thing: It makes fig seeds fertile, thereby enabling populations of figs to sexually reproduce. Thus, as the wasps became established in California, fig trees began sprouting like weeds.

In the Old World, wild figs grow from the cobblestones of ancient architecture, like Roman bridges and castle turrets. In California, their bushy foliage is seen beside parking lots and gas stations, irrigation ditches and chain link fences, train tracks and freeways. I once saw a small fig growing from the top of a palm tree in a San Diego bus station, and a thicket of figs was recently removed from under a highway overpass in San Rafael. Watchful Amtrak riders may see wild figs out the window between Antioch and Martinez.

Introducing the wasp to California opened a Pandora’s box of untasted figs, which are now spilling onto the landscape. The fig wasp’s range is limited by an intolerance of harsh winters, restricting them to the United States’ coastal southwest, but wherever they fly, wild figs grow.

This makes much of the state a fig collector’s paradise.

“To have the generation of new varieties right here, I think it’s so exciting,” Nelson, in Napa, says.

The self-generating engine of the fig-wasp partnership makes fig control efforts seem almost hopeless.

“It’s heartbreaking,” says Katherine Holmes, the deputy executive director with the Solano County Resource Conservation District. “Fig is a terrible invader of a very narrow niche—riparian woodland. It doesn’t invade everywhere, but where it does invade is precious habitat, and it totally takes over.”

Holmes has worked on fig eradication programs in the Central Valley, where F. carica is overwhelming the last remnant parcels of native riparian forest. Holmes says she has personally killed thousands of fig trees using a combination of chainsaws and herbicides, and in isolated spots, including Caswell Memorial State Park, she and her colleagues have had success.

However, the species is only tightening its grip on the landscape elsewhere. The trees spread via root suckers and seed dispersal and can overtake large areas and push out native plants. Holmes says just several percent of the Central Valley’s riparian woodlands remain intact, and fig trees threaten their survival.

F. carica is spreading through Southeast Marin County, and fig seeds are apparently sprouting around the East Bay. The Berkeley-based California Invasive Plant Council’s WeedMapper program, a user-generated database, shows wild fig reports from West Oakland’s Willow Street, the Marina Park Pathway in Emeryville, a suburban yard in San Ramon and a hillside just west of Discovery Way in Concord, among more locations.

Pennington says he often sees enormous wild figs while driving in the Central Valley, but he isn’t particularly interested in inspecting or propagating them. Instead, he has focused on established, if still hard to find, cultivars, many of ancient French and Portuguese origins.

“All these new, terrific figs keep coming along, but if you’re chasing new seedlings, you can’t keep up,” he says.

Most wild figs produce fruit that is dry, pithy or simply unremarkable. One in a handful will produce fruit worth pulling off the road to taste, and among these head-turners, a rare few are standouts. When collectors find them, they keep locations secret and, using evocative, drippy names like Cherry Cordial, Raspberry Latte, Crema di Mango, Gold Rush and so on, they can score thousands of dollars in branch cutting sales.

But the hype quickly tails off as cuttings from the mother tree are distributed far and wide. Soon, the variety becomes an established component of the global fig inventory, and the relevance of the original seedling tree as a source of unique genetics is reduced to another blur of roadside shrubbery.

Fig Swap

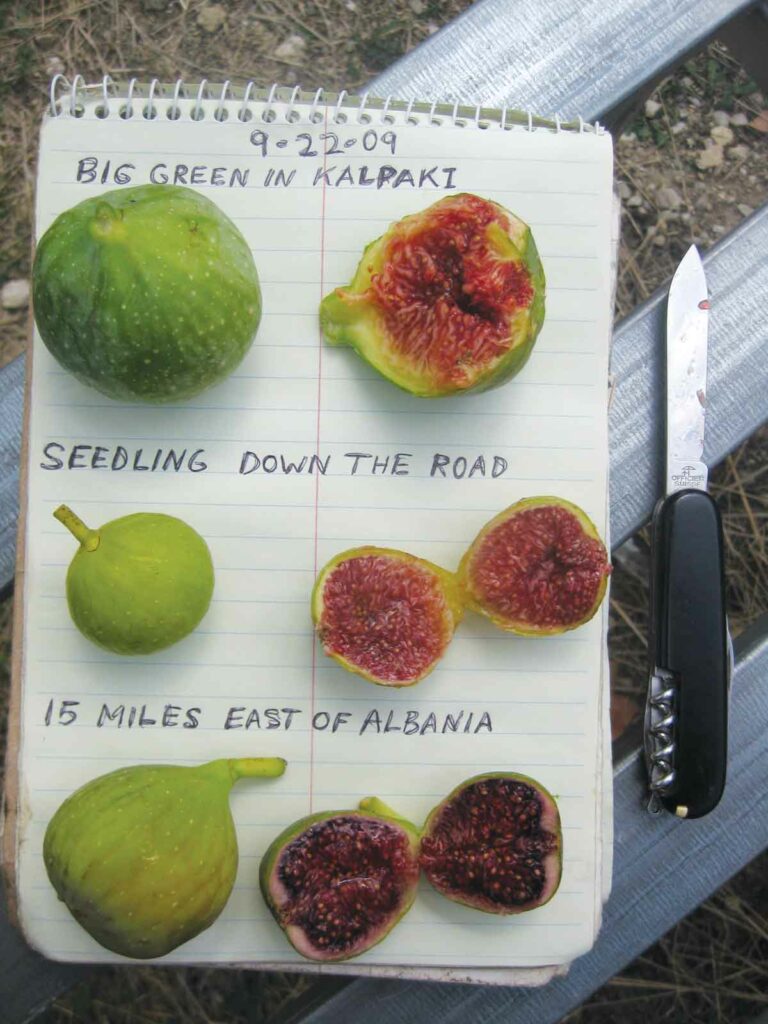

I spent one summer after another in my 20s and 30s bike camping through Europe and Turkey. I got lost in beautiful mountains, weathered terrible storms, dodged men with guns, learned new languages, saw bears and ran out of food—but the focus of those outings was figs. The roadsides offered an unending buffet, and as I cycled between Portugal and the Black Sea, I ate countless fig varieties, interviewed local growers and observed distinctive regional variations in shape and flavor. I even visited government germplasm collections in Greece and Georgia.

Today, my relationship with figs is more grounded. I began building a potted collection around 2014, mostly sourced from unidentified trees in Marin County. When I bought a property in 2017, the floodgates opened. I purchased a few new varieties, replicated ones I really loved, acquired more from other growers, and eventually built up a potted and planted orchard of more than 50 varieties. Twelve feet between trees seemed prudent when I got started; now I’m making excuses for squeezing them in at six feet.

The attraction of the untasted keeps all of us grabbing up more. The day before Christmas, I pay a visit to Pennington’s home to make a trade. I bring him a small Burgan Unknown while he sets aside for me extras of two of his favorites, Bordissot Blanca-Negra and Del Sen Juame Gran, in five-gallon pots. I offer him cuttings of Black Zadar and Grantham’s Royal. If Pennington is trying to cull his collection, which lines his driveway in plastic pots and half wine barrels, I’m not helping.

Figs, in fact, are not Pennington’s favorite fruit.

“That would be a drop-dead-ripe apricot,” he says.

But figs are a close second, and they’re easier to propagate. Indeed, the willingness of a fig branch to sprout roots makes fig trees appealing plants to grow. This certainly drew the attention of ancient peasants, too, who researchers believe began growing fig trees from cuttings before domesticating any other plant. In a paper published in Science in 2006, three scientists, led by Israeli archaeologist Mordechai E. Kislev, concluded that fig trees were “the first domesticated plant of the Neolithic Revolution.” They analyzed fig residue from an 11,000-year-old village in the Lower Jordan Valley that they determined originated in the fruits of “trees grown from intentionally planted branches.”

The game that started then continues now as California fig hunters search for the next prize. With the nonstop emergence of new genetic variants from wild populations, the hunt may never end. In Southern Europe, I believe it may be possible to travel for weeks without ever losing sight of a fig. They grow almost as rampantly as the Himalayan blackberry does here, and eventually the species will likely naturalize throughout California as firmly as it has in the Mediterranean fig belt.

“My hope has been to draw attention to this and do something before we get to that point,” Holmes says.

But Valenzuela sees a thread of poetry in the spread of the species. To him, the trees—which in a sense are followers more than invaders—symbolize the human quest for security and comfort in harsh environments.

“The fig is part of our paradise garden,” he says. “If you’re in the desert, there’s bad weather and animals, but you build a wall and inside you create a protected garden with aromatic plants and fruits. It’s like the Garden of Eden, where everything was perfect, beautiful and abundant. I see the fig as an integral part of that paradigm.”

More than a metaphor, his words take me back many years, to a craggy volcanic island in the Aegean Sea. Against a howling gale, I pedaled my bike to the top of a mountain, where I entered a beautiful monastery. The monk inside, vowed to silence, nodded his greeting and walked me through the dark stone chambers and into the walled garden. Tomatoes and beans grew in the sun, and from a spigot I filled my bottle with icy water. The monk brought a plate of olives, and for a moment I sat in the shade of an old fig.