Esperanza Spalding plays this Friday, Aug. 24, at the Wells Fargo Center in Santa Rosa. I caught up with her on the phone for this week’s music column, but she clearly had much more of interest, and of eloquence, to say than would fit in the paper. Here’s our interview, below:

I read and loved your profile in the New Yorker, and specifically your respect for and appreciation of jazz. But beyond that, I was interested in your comments about playing with McCoy Tyner, and how it reinforced your beliefs that jazz should not be a dusty museum piece, and more a music that needs to be for the present time. I wondered what McCoy Tyner thought of those comments. Did you ever hear from him about it?

Oh, no, I didn’t. But I honestly doubt he’s too concerned about it either way. We talk about it as a conceptual thing, the art form, and that’s good. It’s good to keep the creative juices flowing, the cerebral aspect of it, and thinking about what it means, and where we’re headed with it, and blah blah blah. But the day-to-day reality of making music is just to do it. I mean, that’s the priority, is to sit down every day and explore it. I think there’s a place for every kind of practitioner of the craft. I really have come more and more to believe that, traveling as much as we get to travel—and even living in New York, seeing how much diversity there is of concepts and philosophies about the music, and having those philosophies boil down to the music that’s actually being made.

You have those folks who are total bebop heads, who really see that as the pinnacle of the music. And then there are people who don’t want to have anything to do with that, and say, “Well, that was the language of back then, and now we live in today. We have to keep cultivating the idiom, and forget about that. That was one strand in the stream of what music is, so let’s keep on evolving and not clinging to that.” And the beautiful thing is, there’s really room for everything.

And there should be multiple philosophies in the music, because theoretically, it’s a music that’s open to everybody. And as many different kinds of people there are, there are that many entryways to the music. A person just getting to jazz might really identify with the philosophy of let’s-go-straight-to-bebop, and cultivate that as the true vocabulary of the music. There might be somebody who wants to come to it from the fusion era, there might be somebody who wants to come to it from the swing era. And that’s great.

There’s a popular idea that the way to save jazz is by preserving it and closing it off; the idea I get from you is that you’re maybe inadvertently saving jazz through the notion of opening it up, of making it popular. Is that an accurate thing to say?

No, I don’t think so. As far as “saving jazz”… I honestly think the biggest threat to any art form being able to perpetuate itself is the lack of new devotees. And we live in a time right now where across the board, music programs are cut, and defunded. So I don’t know what one individual’s approach can do to help or hurt the music; I think it’s sort of systemic. The issue isn’t so much about what the musicians are doing or not doing. It has to do with people having access to music, just in general. Having access to music education, or even if they’re not going to be able to become instrumentalists, or pursue it even as a hobby, then having access to live music—understanding music, and having an appreciation for the art in general.

I think that’s the biggest threat to the music. It doesn’t have so much to do with how we’re individually presenting our interpretation of the art form. Because the beautiful thing about a culture that appreciates the arts is that it embraces the artists in all their different permutations, in all the variegated colors and interpretations of any art forms. That’s what you see in dance—it’s not just people doing ballet, or the school of Martha Graham, or people saying “Alvin Nikolai’s the truth, and after that, forget about it.” In a culture that’s thriving and appreciates dance as an art form, people will want to see every kind of dance.

So I guess what is most disconcerting, and what we really need to focus on, is how are young people—and all people—going to be exposed to the arts, and have a cultivated appreciation for what art is? For what music is? For what the creation of a piece of work is? Not just for the sheer entertainment value, but really valuing what it is that a true artist does. A true artist will cultivate themselves to be a finely tuned conduit to manifest something of another realm, so that when a non-musician or audience member experiences it, they also get transported to that realm, or get to savor a taste of what it is the artist cultivated. That is the relationship that we need for any art form to thrive, or be saved, or however you wanna look at it. I think if young people of any age are not living in a culture where that aspect of art creation is appreciated, no mater what we as artists do for the music, it’s gonna be a sinking ship.

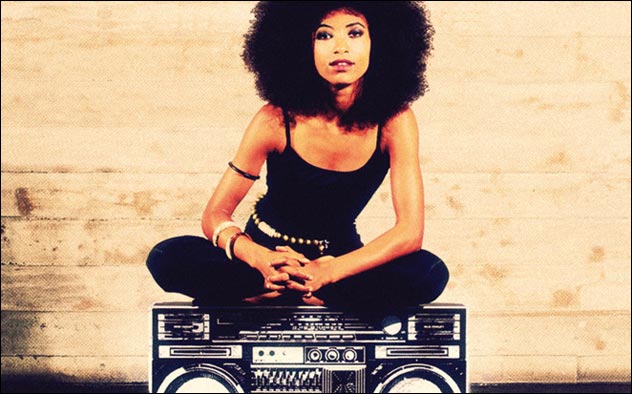

Which leads me to ask about the name of your latest album, Radio Music Society. The idea of the radio is so populist—it’s designed, by nature, for the people. Was that a theme you chose intentionally?

Which leads me to ask about the name of your latest album, Radio Music Society. The idea of the radio is so populist—it’s designed, by nature, for the people. Was that a theme you chose intentionally?

Yeah. The radio’s exactly that. It’s a free resource. I mean, you have to listen to a few commercials. But generally, it’s free! So everybody’s equal. Whatever kind of music you like, whatever economic strata or background you come from, you can turn the thing on and hear what anybody else is hearing. I think that’s a beautiful, powerful tool for exposing the general public to art. And the pity is it’s been taken hostage by these really strict rules, these programming rules that have to do with making sure they get the most listenership of this demographic that will make the advertisers happy. It’s this public resource, but the public has so little say on what actually makes its way there. When I think of the issue of jazz accessibility, I don’t think of the content so much as how the hell will someone ever get to hear the music? If you don’t already know it and love it, how will you access it?

So I guess part of the premise of the radio being the theme, was that the radio is a medium through which the general public at large can access good quality music, for free. And I thought: what can we do in this particular project, this band—it’s not a question I’m sending out to the community at large, it’s just a challenge to myself and my direct colleagues—what can we do to the music so that we feel proud and confident that what we’re sending out is a true representation of the art that we love, and, maybe through an arrangement, or through the sonic quality, or how we record it or whatever, we can do things that might give it a better chance of ending up on mainstream radio?

And we failed. I failed in the sense that every song is longer than three minutes, which automatically disqualifies it, and they all have instrumental solos, which pretty much automatically disqualifies it. But I was hoping that there might be some sympathetic DJs out there that would hear what is familiar to quote-unquote “mainstream” audiences in the music, and give the musicians a chance to be heard by the audience at large. And give the general public a chance to find out if they like Joe Lovano, or Terri Lyne Carrington, or Lionel Loueke, or Algebra Blessett.

You’re right, you do make some bold choices on the record, both musically and lyrically. There’s a song, “Land of the Free,” about Cornelius Dupree. Did you follow that case closely, or was that song written as more of a quick reaction to what happened?

It was a quick reaction. I didn’t know anything about the case. I mean, I have a dear friend who works in a state prison who’s really involved in prison reform, and prisoner rights, so I was aware of similar cases, similar situations, but I just saw this press conference thing—I don’t even know what you would call it—where this gentleman had just been released after serving for 30 years. And just the way he spoke was so potent, and so impactful, I don’t know, it was very impulsive—I just said “Oh my God. I don’t know what to do.” But I couldn’t live with the feeling, so I had to put it through the medium of a song. And then I thought a constructive follow-up to the impulsive action would be to associate myself with the Innocence Project. So they’re coming on the road with us in the fall to raise awareness about what they do, and funds for what they do. And proceeds from that song, or part of it anyway, go to the Innocence Project.

Also, there’s the song “Vague Suspicions.” I’m curious about the lines that reference a drone strike killing civilians—you probably know that President Obama has defended the use of drone technology. And have you… I guess what I really want to ask is, did you talk with him about it ever, when you played the White House?

No. I never had a chance to talk with anybody. And I wouldn’t ever be so brash as to even try. I’m not educated enough, I just know what I feel about what I read, and what I understand from the historical context.

But you know, just relating to that—that the President says he approves of it, he endorses it—I was just watching this film, Letters From Iwo Jima, and there’s this scene with this Japanese general, but it’s before the war starts, he’s in the United States. He’s friends with these Americans, and people within the military, and a lady asks him, “What would you do if the U.S. and Japan went to war?” And he says, “Well, I would have to act according to the motivations of my country.” And she says, “So you would try to kill my husband?” And he says, “Like I said, I would go with what I thought was right.” And she says, “What you thought was right, or what your country thought was right?” And the Japanese man looks at her and says, “What’s the difference? Isn’t it the same?”

I think that’s an important thing to note. When we listen to what politicians say, it’s not their personal opinion. We theoretically wouldn’t want a president or anybody else to act on their personal feelings or perspectives. Theoretically, you elect your president, or senator or representative into office so they’ll reflect what the majority sentiment is, right? So I never get too up in arms when I hear any politician speaking. You can’t take it personally for what they are. For whatever reason, that’s what they think they have to say on behalf of fill-in-the-blank.

And it’s not just drone strikes. However you wanna slice it, war equals death. And there’s bound to be mistakes. I was just reading an article yesterday from the perspective of soldiers who are not on the ground in Afghanistan, but actually somewhere in the Midwest in a studio, with these big screens, driving, with a joystick, these drones. And they speak about the emotional experience of watching these “insurgents,” quote-unquote, go about their daily lives, and kiss their children, and have dinner with their wives, and visit their neighbors, and they talk about the emotional turmoil they go through when they shoot them. When they kill them. And saying, “Of course it’s really hard when we accidentally hit a child, of course it’s really hard when we accidentally kill innocent civilians.”

I just feel like the dialogue – we’re so used to hearing these phrases, and these words, that maybe we’re not remembering what that actually represents. It represents a human being, and a life, and a young child that was killed. And we hear it so much that maybe there’s a numbness to what those phrases actually boil down to on the ground in terms of the value of human life. Those are the thoughts that were running through my head when I wrote that song. I take these catch phrases, and wait, wait, wait, wait a minute, what does that mean? What does it mean that “possibly there were 12 civilian casualties”? What the hell does that mean? Heaven forbid anyone I love or know becomes a “civilian casualty” for when a bad guy gets shot.

It’s no big point to make; it’s just something I became aware of and needed to write about.

I have to ask about Prince. Can you sum up what you’ve learned from playing with him?

Knowing how badass you are as a musician. The audience doesn’t want the illusion to be broken that something extra human, extraordinary, and magical and stimulating is happening. I’ve seen him on so many occasions, in the heat of the moment, come up with the most amazing creative way to solve a technical problem, or communicate something to a musician, or whatever. It’s undeniable that his musicianship is stellar—he plays every instrument, and he sings amazing, and dances amazing—and on top of that, he’s so aware of the total experience being projected from the stage. And he’s able to keep the experience perfect. There’s never going to be a hole poked through that experience he’s projecting. And that aspect of his creativity is just as important as rehearsing a song perfectly. It’s just been amazing to see that. Sometimes, when we talk about my own concerts, he gives me feedback about, like, well, you know if you’re trying to convey this right here, I know what you meant but I didn’t quite get it, so you might try moving a little bit, or saying this, or whatever. To really make sure that the data you want to clearly be received by the audience is being received in the way you intend it to. That’s something he’s a master of. Knowing him and talking him about that—and watching him—has made me more conscious of that.

One last question. Last year, you won Best New Artist at the Grammy Awards, beating out a certain pop star. I know there were a lot of fans of Justin Bieber who were not very thrilled about it, and you received a lot of vitriol from them, particularly online. Were you able to blow that off? Did it shock you, the rage that was directed at you?

No. I mean, what are you gonna do? That was nothing. I think that was a total farce. And I remember what it’s like to be a preteen, or a teen, and something happens, you get so emotional about it. It seems like the end of the world. You trip in front of the school bus and kids laugh at you—you’re thinking about that for, like, a week. Or some boy you like in school laughed at you, or sees your underwear or something, and it seems like the end. And it’s nothing, you know. It’s really nothing, in the grand scheme of things, or even in the small scheme of things.

The pop star you’re referring to has gone on and will continue to go on to have a great successful pop star career, whether or not his fans are mad at me, and I will go on and continue to do my thing whether or not his fans are mad at me. And I’ve met kids who are big Justin Bieber fans, and they come to my shows, and they go, like, “I was really mad when you won, but, it’s okay. I forgive you now.” So it’s really just all good.

TRENDING:

Extended Play: Esperanza Spalding on Justin Bieber, Jazz Purism, Drone Strikes and Playing With Prince