At 11am on a Sunday morning, I slip into a row of seats in front of a podium with flower bouquets on each side. I’m here to listen to an aging white man talk about the afterlife. A woman in a fancy hat arranges a potluck lunch on a back table. Other attendees, mostly gray-haired, pass around a wicker basket and toss in $20 bills and personal checks.

We aren’t in church. This is godless Silicon Valley.

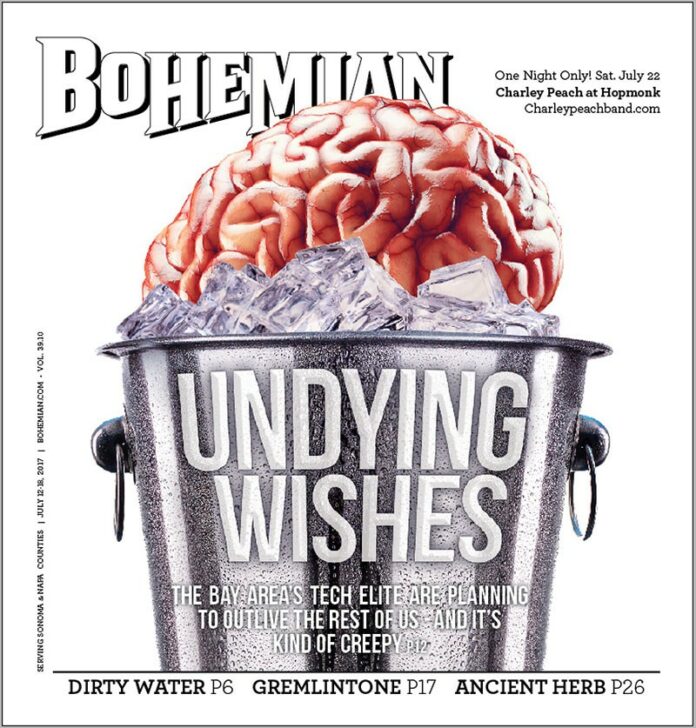

The Humanist Society has welcomed Ralph Merkle, a Livermore native, to explain cryonics—the process of freezing a recently dead body in “liquid goo,” like Austin Powers—to the weekly Sunday Forum. We all want to know about being re-awoken, or reborn, in the future.

Merkle, who has a Ph.D. in electrical engineering from Stanford and invented what’s called “public key cryptology” in the ’70s, makes his pitch to the audience: hand over $80,000, plus yearly dues, to Alcor, and the Scottsdale, Arizona–based company will freeze your brain, encased in its skull, so that you and your memories can wait out the years until medical nanotechnology is advanced enough to both bring you back from a frozen state as well as fix the ills that brought on your death in the first place.

“You get to make a decision if you want to join the experimental group or the control group,” Merkle says. “The outcome for the control group is known.”

Alcor gained infamy in 2002, when the body of baseball legend Ted Williams was flown to the company’s Arizona headquarters, where his head was then severed, frozen and, according to some reports, mistreated.

The Humanist Society is an ideal audience for Merkle’s presentation, as its congregants aren’t held back by the tricky business of believing in a soul. Debbie Allen, the perfectly coiffed executive director and secretary of the national board of the American Humanist Association, considers cryonics a practical tool. “Religion has directed the conversation for thousands of years,” she says. Allen prefers to focus on ethics, and whether cryonics “advances the well-being of the individual or the community.”

“Science-fiction,” someone whispers behind me, as Merkle talks about nanorobots of the future. He also notes how respirocytes and microbivores can be “programmed to run around inside a cell and do medically useful things like make you healthy.”

As one might expect in a room full of humanists, skepticism runs high during the Q&A portion of the meeting. People are wondering exactly what kind of animals the scientists have used to test the cryonics process (answer: nematodes); when Alcor freezes bodies (after one’s heart stops, if a DNR, or do not resuscitate, order is requested); whether a frozen brain is any good if the rest of the body deteriorates (“Toss it,” Merkle says. “Replacement of everything will be feasible.”); and what happens if Alcor goes bankrupt.

“We take that very seriously,” the doctor says.

Lunch is served.

“Why would he want to preserve somebody like Adolf Trump?” asks Bob Wallace, 93, who ate salad and cubed cheese with his partner, Marge Ottenberg, 91, whom he met at a Humanist Society event.

“Obviously, the worst possible people are most likely to want to live forever,” says Arthur Jackson, 86, a retired junior high school teacher.

Ottenberg seems more open to the idea of coming back from the dead than her golden-year counterparts. “Whatever works,” she says.

Silicon Valley is the sort of place where people dream about nanorobots fixing our medical disorders. It’s the sort of place where hundreds of millions of dollars are spent chasing that dream.

The last five years have seen an investment boom in what’s called “life extension” research. Some of it is straight-up science, such as the Stanford lab researching blood transfusions in mice to cure Alzheimer’s. Scientists are in a race against time to help as many people as possible, as fast as possible. They’re battling a disease that saw an 89 percent increase in diagnoses between 2000 and 2014; and Alzheimer’s or other dementia is currently the sixth leading cause of death. There are also nontraditional sources of cash flowing into biotech, which was once considered a risky investment.

But death itself is the biggest social ill Silicon Valley is trying to solve.

We can build apps to keep track of diabetics’ blood glucose levels, to measure how soundly we’re sleeping and to access medical records in an instant, but none of this stops the body from wearing out. Alongside the scientists laying the medical foundation to get us to the nanorobots envisioned by Merkle, techie utopians are looking at other ways to cheat death. A cluster of tech companies are attracting far more funding from Silicon Valley than academia, shifting the research landscape with infusions of cash.

Bryan Johnson, an entrepreneur who sold his online payment company to PayPal for $800 million, was the first investor in Craig Venter’s Human Longevity Inc., which aims to create a database of a million human genome sequences, including people who are over 100 years old, by 2020. Oracle founder Larry Ellison, who once said “Death makes me very angry” and is one of the oldest of the life-extension investors at 72, has also invested in Human Longevity. Johnson infused even more cash into the biotech field, investing another $100 million of his own money into the OS Fund in 2014, to “support inventors and scientists who aim to benefit humanity by rewriting the operating systems of life.”

Such projects are examples of Silicon Valley’s extreme confidence in its own ability to improve the world. In an email, Johnson describes his work in grandly optimistic terms.

“Humanity’s greatest masterpieces have happened when anchored in hope and aspiration, not drowning in fear,” he says.

It takes some serious chutzpah to say you’ll extend the human lifespan, and for Johnson, he and his colleagues are venturing where no one has gone before.

“Building good technology is an act of exploration, and that it is very difficult for us to imagine the good that might come from any new technology,” Johnson says. “We proceed, as explorers, nonetheless.”

Johnson’s lofty goals are similar in scale to other giant anti-aging investments in Silicon Valley. In 2013, Google created an anti-aging lab called Calico (for “California Life Company”), hiring top scientist Cynthia Kenyon, known for altering DNA in worms to make them live twice as long as they usually do. Calico is not your local university research lab; it has $1.5 billion in the bank and has remained close-lipped about its progress, like a Manhattan Project for life extension.

For Google co-founder Sergey Brin, 43, Calico may be another way to attack a more personal health concern: Brin carries a gene

that increases his likelihood of contracting Parkinson’s disease and has already invested $50 million

in genetic Parkinson’s research, conducted by his ex-wife’s company, 23andMe. Brin said in 2009 that he hoped medicine could “catch up” to cure Parkinson’s before he’s old enough to develop it.

That hope is a common thread among health-obsessed tech investors like PayPal founder Peter Thiel, 49. A libertarian and Trump adviser, Thiel is trying to avoid both death and taxes. His foundation hired a medical director, Jason Camm, whose professional goals include increasing his clients’ “prospects for Optimal Health and significant Lifespan Extension.” Like Brin, who swims and drinks green tea to prevent Parkinson’s, Thiel has changed his daily habits to live longer. He’s aiming for 120, so he avoids refined sugar, follows the Paleo diet, drinks red wine and takes human growth hormone, which he believes will keep bones strong and prevent arthritis.

Thiel has also expressed personal interest in a company called Ambrosia in Monterey, where

Dr. Jesse Karmazin is conducting medical trials for a procedure called parabiosis, which gives older people blood plasma transfusions from people between 16 and 25. Karmazin has enrolled more than 70 participants so far, each of whom pays $8,000 for the treatment. Much has been made of Thiel harvesting and receiving injections of young people’s blood, though Karmazin recently denied that Thiel was a client of his.

Karmazin doesn’t call himself a utopian, but he does note that his work requires some faith. “There’s always uncertainty about whether it’s going to stand the test of time, whether it’ll work at all,” he says. “That’s especially true in technology, and you have to believe in it.”

At the same time, the dystopians of Silicon Valley are preparing for the apocalypse. Reid Hoffman, CEO of LinkedIn, told the New Yorker that he guesses up to 50 percent of tech executives have property in New Zealand, the hot new hub for the end of the world. Steve Huffman, CEO of Reddit, bought multiple motorcycles so he can weave through highway traffic if there’s a natural disaster and he needs to escape. He also got laser eye surgery so he wouldn’t have to rely on glasses or contacts in a survival scenario.

Among the dystopians is Elon Musk, whose brand-new Neuralink company is investigating what Musk calls “neural lace,” a digital layer on top of the brain’s cortex that connects us to computers. Such inventions could eventually lead us to what Google director of engineering Ray Kurzweil calls “technological singularity,” or the time when ever more powerful artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence, around 2045.

[page]

Musk is nervous about that day, and part of the reason he wants to colonize Mars through his SpaceX plan is because humans need an escape route in case computers take over—or, perhaps, in case of environmental apocalypse. Musk recently quit two of Donald Trump’s business advisory councils over the president’s decision to leave the Paris climate accords, tweeting, “Climate change is real.”

Tech companies as a bloc urged Trump not to leave the Paris agreements; Tim Cook of Apple called him after the announcement to try to get him to change his mind, and Mark Zuckerberg wrote on his Facebook page that leaving Paris would “put our children’s future at risk.”

Zuckerberg has been trying for years to knock down four houses to build a residential compound in Palo Alto, that includes a basement structure that sounds like a bunker perfect for hiding the whole family if the world ends.

Whether climate change destroys California or regular old death arrives before investors have funded a cure, Musk, Zuckerberg and their elite peers have the resources to plan an escape. The question is whether they’re interested in planning anyone else’s.

Tony Wyss-Coray, director of the Stanford Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, which is on the forefront of anti-aging research, has seen that conflict up close.

“I have been approached by billionaires from L.A. and Texas, and they already have their clinics in the Bahamas or wherever, where they inject themselves with stem cells,” he says.

But those billionaires weren’t interested in funding his lab or curing disease for anyone else.

“They’re interested in living,” Wyss-Coray says. “They realize quickly they can’t buy this directly from Stanford University.”

The line between science and someone’s obsession with mortality is blurry, especially with this much cash flowing.

“It’s hard to completely disassociate the influence of wealthy, rich people from what we do,” Wyss-Coray says. Until the recent influx of funding and attention, the anti-aging scientists he knew “were just a bunch of academic geeks” studying worms. He’s interested not in extending life as much as figuring out why certain people can live past 100 years old.

“The average person at 60 or 65 starts to suffer from a multitude of age-related diseases—arthritis, heart disease, cognitive decline—that for some reason the centenarians seem to be able to escape from, and that’s what drives many of us in the field.”

But when Thiel is reading one’s research, things get more complicated. Wyss-Coray’s studies on the benefits of parabiosis in mice, for example, form the basis of the Monterey trial that so fascinates Thiel. Wyss-Coray is quick to distance himself from Karmazin. “He cites all our work on his website,” Wyss-Coray says.

The first two studies in the “Science” section of the Ambrosia website are from Stanford’s labs, and the first study Karmazin lists about plasma transfusions in mice is Wyss-Coray’s.

Many scientists consider clinical trials like Karmazin’s unethical and scientifically unsound, since they require participant payment for unproven treatments, and you can’t charge someone $8,000 for a placebo, so there’s no simultaneous control group. The Ambrosia trial passed an ethical review, but Karmazin acknowledges the criticism.

“Some people are opposed to it for ethical reasons,” he says. “That’s understandable, but I still think it’s worth doing, so I’m trying to treat people.”

Wyss-Coray is ambivalent about his research being exploited for profit. “You contribute a small piece to knowledge that frequently can be abused by somebody,” he says. “I feel somewhat guilty, but I hope at the same time, we can contribute to maybe having an impact on some diseases, and that will be offset.”

Back under the fluorescent lights at the Humanist Society, Merkle explains that in addition to freezing themselves, people can use Alcor as a bank, putting money aside so that they don’t wake up poor in a hundred years. Future poverty is a common enough concern that Merkle includes it in his presentation. Why would anyone want to live forever if it meant working three jobs to survive?

Indeed, people who are struggling to pay rent right now won’t be able to afford to freeze themselves, so anyone waking up from cryogenic sleep will be wealthy, and most of them will be white, just like the bros pioneering biotech startups and building underground bunkers. Indeed, about 75 percent of Alcor’s frozen customers are male, and Max More, its CEO, is a libertarian like Thiel. The men who have everything want to keep it all, indefinitely.

Income inequality makes life extension the ultimate oligarchical fantasy. A month before Gawker shut down last year, bankrupted by Thiel’s campaign against it, reporter J.K. Trotter mused, “It’s not hard to imagine a Thielist future in which members of the overclass literally purchase the blood of the young poor in order to lead longer, healthier lives than their lesser counterparts can afford.”

In Thiel’s libertarian universe, the luckiest people could live forever, feeding on the blood of teh Bay Area’s youthful underclass—

Hey there, renters!—and living on extra-governmental barges like the seasteads Thiel dreams about, without paying taxes to help anyone else. Floating cities might be helpful if flooding and erosion destroy the California coastline, as CALmatters’ Julie Cart reported could happen 70 years from now.

Taking the scenario a little further, birth would be unnecessary, since no death would mean no one would need to be replaced. That might make people with wombs a little less than necessary, as well, especially if those barges are populated with the new crop of alt-right dudes who sleep with men because they worship masculinity.

Thiel, who is gay, would probably find it preferable to get by without women; he considers date rape as “belated regret” and once blamed women’s voting rights for the eventual demise of democracy. His worldview is the warped conservative version of feminist theorist Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, in which she imagined the freedom in a “world without genesis, but maybe also a world without end.” Back in 1984, Hathaway predicted a future where we merged with machines, but warned against letting “racist, male-dominant capitalism” control technology, since hippie progressives are not cheerleading the convergence of humans and machines.

It might all sound far-fetched, but Thiel shares an anarcho-capitalist worldview with White House senior adviser Steve Bannon, among the most powerful people in America right now. And the House passed a healthcare law that saves money on insurance by letting poor people die faster, moralizing that poor people don’t want to be healthy.

Californians may not agree with that law outright, but Silicon Valley’s bootstrappy cult of health is based on the nerds’ association between fitness and brainpower. They’re taking up kiteboarding, tracking steps on Fitbits and eating ketogenic diets during stressful times at startups. It’s not a big jump to life extension for the rich, who deserve to live longer after all that effort.

Are the ethics of life-extension technology any different from historical questions of who gets access to medicine? Maybe not.

Karmazin hadn’t yet considered the topic before our phone call. “I haven’t had this kind of conversation with anyone yet,” he says. But Karmazin compares his trial to the introduction of antibiotics. “Someone who didn’t have access to antibiotics when they were invented—man, they’d probably be really upset. That’s reasonable.” He foresees similar problems with blood plasma as a cure for aging: “I think it’s going to be unevenly distributed.”

Wyss-Coray has serious concerns about that distribution.

“We have enough problems in the world already, and I definitely do not want a select group of people to live longer just because they can afford it,” he says.

In this country, the richest 1 percent live 15 years longer than the poorest 1 percent, meaning Wyss-Coray’s fear is already our reality. The question is how much worse things can get, and whether a medically assisted longer life will be inaccessible to almost all of us.

That’s assuming, of course, that we even want a longer life, or to wake up after a cryogenic sleep. We may value our time on Earth, but not everyone thinks it’s worth it to stick around indefinitely.

If your Silicon Valley brain sees the world as a place of obstacles that can always be overcome—where every system can be disrupted for the better and your brain is the one that will unlock a better future—you might be more inclined to stay. That might also be true if you think the universe is a place to conquer, whether via spaceship to Mars à la Musk or through politics like Thiel.

But what might the future look like, for those who want (and can afford) to stay?

Google’s Kurzweil envisions three medical stages before singularity, starting with our current push to slow aging. Stage two: building on genomic research, including personalized fixes for diseases like cancer. Kurzweil believes we’ll get to the medical nanotechnology that Merkle envisions by the 2030s, which would lead us to the last phase—nanorobots connecting us to “the cloud” in 2045. At that point, avatars of our brains could be loaded into another body. Then we’d live forever.

Bodily ailments would be curable and we’d access consciousness from the cloud, but we’d still lose our memories when our physical brains stopped working. A better (and still terrifying) option might be freezing our brains via cryonics and then bringing them back with nanorobots.

Kurzweil has signed himself up to be frozen, in case the 90 supplements he takes daily don’t keep him alive.

Wyss-Coray has chosen not to go into the meat locker. “I can’t think of any way to connect that to what we’re doing,” he says. “I haven’t signed up for that myself.”

Neither have most other people. Cryonics remains unproven, cost-prohibitive and unusually creepy to the general population, an option for the rich and famous who would need several lifetimes to see their savings run dry. At this rate, they’ll likely outlive us, so we might as well enjoy some refined sugar, pay our taxes and stop fearing the reaper.