When he’s not writing, Jonah Raskin is writing; which is to say he is always writing.

The prolific author and frequent contributor to the Bohemian and Pacific Sun seems to publish something every year. And nothing changed during the pandemic.

Out now, Raskin’s latest literary wonder is the novel, Beat Blues: San Francisco 1955, which features fictional cameos by several of the city’s famous and infamous members of the Beat Generation, including Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

“It started as a love story between Natalie Jackson and the protagonist Norman,” Raskin says.

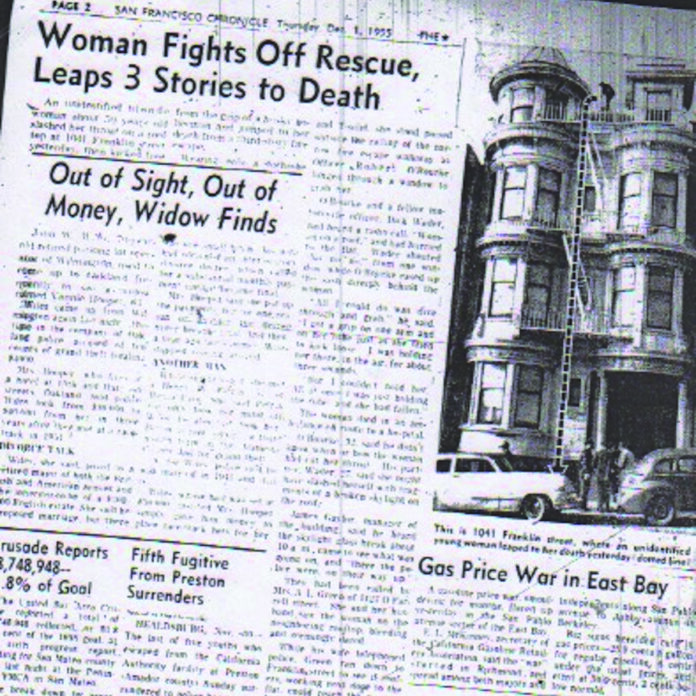

Jackson became a notorious figure of the Beat Generation for having an affair with Kerouac’s buddy, Neal Cassady, before committing suicide in San Francisco in November of 1955. Yet, very little is actually known about Jackson other than the tabloid headlines of the time.

Several years ago, Raskin began looking deeper into Jackson’s life with the help of his brother, who is a private investigator. From there, Raskin decided to put Jackson in this novel, which led him to set the action in San Francisco in 1955. Then he incorporated iconic spots, such as City Lights Bookstore and the Blackhawk jazz club, and began including other Beats in the story.

Coming off of writing three noir detective stories, Raskin says there is some darkness in Beat Blues, but it’s not a whodunit. Rather, the story offers a behind-the-scenes look at the culture of jazz and poetry that permeated the city in the 1950s.

“1955 was also the birth of the Civil Rights movement, and there was the murder of [Emmett Till] in Mississippi,” Raskin says. “So I brought together in the novel these two sides of the mid-50s, the Black Civil Rights movement and the mostly white cultural revolution of the Beats. They’re interacting.”

In the novel, Raskin also puts words in the mouths of Beat figures like Ginsberg, who Raskin invited to read and lead poetry workshops at Sonoma State University, and City Lights Bookstore-owner Ferlinghetti, who Raskin also knew.

“I took more liberty with Natalie Jackson than with the other characters, because there are more blank spaces in Jackson’s life than their lives,” Raskin says. “Kerouac says Jackson was a writer, but as far as I know, none of her work exists. So, I did take the liberty of having Jackson perform one of her poems publicly, and she’s kind of outrageous. In a way, she’s a liberated ’60s woman before the ’60s. She points the way to the future even though she didn’t make it there herself.”

In the following excerpt, from Chapter 10 of Beat Blues, Norman reconnects with Natalie Jackson at San Francisco’s Blackhawk jazz club. Beat Blues: San Francisco, 1955 is now available online and in bookstores.

–––

The Blackhawk felt funky, as in rough around the edges, and funny, as in strange, not ha-ha funny. Except for a few couples who might have been described as “interracial,” white folks and Black folks sat at separate tables, with only jazz to bring them together. The place wasn’t segregated, but it wasn’t really integrated, either. A few young kids accompanied adults and sipped through straws from bottles of Coca Cola.

A couple of guys who struck Norman as queer leaned against the bar and a couple of women he thought of as lesbians stood near the back wall. This place is gonna be raided, Norman thought. I don’t want to be here when that happens. His paranoia was acting up again.

He remembered that he had first heard bebop in Harlem six months after he came home from the war. At first, he resisted it and wanted to go back to the days of swing and the big bands when he danced in a clumsy, albeit graceful sort of way. He missed the dancing, missed Gene Krupa on drums and Dizzy on his horn, but bebop wore down his resistance, swept him up and carried him away.

Dancing, he decided, was for squares. He had been a weekend hipster. Now he was a fulltime hep cat. The sax became his deity; he worshipped at its shrine. No wonder he heard it at odd hours and in odd places.

Ezra arrived at the Blackhawk after the first set came to a close, and found Norman seated at a small round table, where he sipped a cocktail. Norman reached discretely for the brown paper bag in his jacket and surrendered it before Ezra asked for it. His pal held it in the palm of his hand, scampered across the floor and ducked behind the curtain on the stage.

A few minutes later, Lester appeared with his sax for the start of the second set and began to play slowly and sweetly. He transported Norman to a place that felt blissful. A photographer took Lester’s picture with the band members, and pictures of the audience, too.

Ezra returned to the table, sat down, folded his arms across his chest and let the music wash over him. It helped that he was stoned. There was no doubt about it, the reefer had worked its magic. Norman could smell it.

But it wasn’t just on Ezra; it was all over the Blackhawk, mixed in with, but not dominated by the smell of tobacco, beer, perfume and perspiration. Norman’s own bittersweet longings welled up from inside and made him feel hornier than he had felt for a long, long time. Perhaps he had a contact high.

Ezra clapped Norman on his back and roused him from his reverie.

“You did right bro! The cops didn’t find nothin’ on me. Let me go once I showed my driver’s license and papers from the army. I carry ’em to keep me outta trouble.The uniform didn’t hurt, neither.”

Norman surveyed the room.

“Great show! Fantastic audience. I could stay here forever.”

He noticed parents with their children in tow.

“What gives with the kids?”

“They gotta get with jazz same as adults.”

“What about the guy with the camera?”

“That’s Fred Lyon. He nails ’Frisco, from the Golden Gate to Coit Tower and Nob Hill; he’s famous all over town. If you pay him he’ll take your photo.”

Norman watched Lyon move around the room like a dancer, snapping shots of the audience, as well as shots of Lester Young, who wore a pork pie hat. Norman fixed his eyes on Ezra, who didn’t look or sound like the man he had seen on the sidewalk, hemmed in by the cops. Ezra snapped his fingers. His head bobbed up and down.

“Man, oh man, Prez is hot tonight. Did you hear that riff?”

“I did! It’s better to hear him in person than to hallucinate his harmonies.”

When Lester played “D.B. Blues” Ezra looked like he was lodged in jazz heaven.

“Fuckin’ outrageous that he was busted with booze and reefer, locked up, kicked out of the military and court-martialed.”

“Dishonorably discharged! Disgraceful!”

Ezra’s lithe black body moved to Lester’s elastic blues.

Seemingly taller and more robust now than he had been on the street surrounded by the cops, Ezra leapt to his feet, sashayed across the room, pulled up a chair and sat down at a table opposite a woman who wore a purple evening gown that revealed her back. In his spiffy uniform with his hair slicked back, Ezra looked, Norman decided, like a confidence man who might talk a man or a woman into or out of most anything. He was cheeky.

Norman could not see the woman’s face, though he twisted this way and that way and tried to find a clear line of sight. There were too many people sitting and standing between them. Her face was turned away from him, though for a few moments he had a good look at her slender neck and shoulder blades.

He thought he remembered them, especially now with the sax swirling around and around. Lester, the funky bebop king and the woman with the beautiful shoulder blades, a white queen reigning effortlessly over the crazy scene at the Blackhawk. Norman didn’t want to be her vassal, or express his fealty, and he resented the intimacy she seemed to share with Ezra, her Black prince.

The Blackhawk was a kind of pressure cooker that heated everyone. It intensified Norman’s red hot rage and his cool green jealousy, and something he didn’t want to know and acknowledge, the noir at the heart of noir: the Blackness of his own whiteness.

His ancestors were talking to him, though he didn’t want to hear them. He calmed himself down by sheer willpower and crossed the room at a diagonal, the music growing louder and louder. He glanced over his shoulder and found Natalie’s flinty eyes—yes, yes, Natalie’s eyes—as hers found his, their eyes locking until he blinked, his head pounding.

Lester was fucking his sax, the music rising and falling until it climaxed and the room thundered.Then came a moment of silence and clarity. Natalie had the same hard eyes and soft mouth that he remembered.

Who am I? He asked himself. Who is Norman de Haan, who traces his ancestors from Holland to Suriname on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean? He didn’t like to admit it, but he thought that the white queen was threatened by the Black prince, who was supposedly his buddy and obviously as queer as the queers who stood at the bar. Race trumped everything every time. It whipped friendship, sex and class, too.

Where was his Oreo self now? Nowhere. He was white on the outside and white on the inside.

“Mind if I join you?”

Norman didn’t wait for an answer. He grabbed a nearby chair, sat down and drilled Natalie with his eyes.

“Long time no see.”

He was instantly embarrassed by the cliché that told him he was at a loss for words. It was cliché time at the Blackhawk. The clichés piled up and crashed down to the floor along with the notes that spilled from Lester’s sax.

There they were, the three of them: the two army veterans and the woman between them. New York Norman and San Francisco Ezra, East entangling with West, white coexisting and colliding with Black, and the noir queen at the crossroads. There would be no balancing act. Something or someone had to give. It wasn’t going to be Norman. He would stand his ground, even if there was no ground to stand on.

Ezra piled another cliché on the pyramid of clichés.

“I might as well break the ice.”

To Natalie he said, “This is my buddy, Norman,” and to Norman, “Meet Natalie, a Jersey girl, just blew into ’Frisco.” At least he didn’t say “my girl.” Norman was thankful for that. Maybe Ezra went both ways. Maybe he bedded women as well as men.

Norman vowed not to seem too curious and vowed, too, not to toss out another cliché. He didn’t want to utter another fake phrase, or make a face that would reveal his invisible connections and disconnections to Miss Natalie Jackson, formerly of New Jersey.

She was more beautiful than he remembered her, more womanly and less girly, more sophisticated and less rough around the edges. He knew he was still dangerously in love with her.

“Pleased to meet you.”

He tried to hide the embarrassed expression he was sure had to be on his face. He wanted to slap himself.

Natalie wore a bemused smile that seemed to belie her anxiety.

“Pleased to meet you, too, Norman. Do you come here often?”

Norman shook his head.

“No, this is my first time.” Once he started to talk, he couldn’t stop talking. Words concealed his own nervousness.

“Ezra brought me here and I’m glad he did. Lester is amazing and the Blackhawk is the coolest club I’ve ever been to, including Birdland, though Bird was phenomenal until he started shooting up. Truth to tell, I love Shearing’s lullaby to the place. It’s a classic.”

He heard himself speak and thought he sounded like his glib prof in Jazz 101.

Natalie lifted her cocktail glass.

“Bebop is ancient history.You should hear ‘Shake Rattle & Roll.’ It’s the newest thing. I have a stack of 45 RPMs. You know, don’t you, the DJs call it ‘rock ’n’ roll’ and say it has already blown bebop out of the water. Elvis is bound to hit ’Frisco ASAP.”

Norman wanted to be cantankerous.

“I would not like bebop to go the same way as the novel, which is dead or at least dying, according to my friends who read Partisan Review.”

He turned toward Ezra.

“What about you, pal. What do you think?”

Ezra took a deep breath.

“I’m partial to Muddy Waters and Ray Charles and turn a deaf ear to the Crew Cuts, and as for Patti Page, that doggie in the window she sings about ought to pee all over her lily white shoes.”

Natalie laughed until her whole body shook. She turned from Norman to Ezra and then back to Norman, and wore a smug expression on her face that said she wanted to pick a fight.

“You sound like you’ve got a stick up your royal Dutch ass.”

“No reason to jump at every new fad.”

Norman growled.

Natalie growled back.

“It’s not a fad.”

“What is it if not a fad?”

“You wouldn’t understand.”

Ezra listened to the verbal volley with amusement and seemed disinclined to add his own feelings to the mix. But then he broke his stony silence.

“If you pay attention to rock and roll, you’ll hear rhythm and blues.” He didn’t say “rock ’n’ roll” or “rhythm ’n’ blues.” He used the word “and,” which lent a certain formality to the terms.

Natalie glared.

“If you listen, you’ll hear country and western in rock.”

Ezra huffed.

“A lot of white boys tryin’ to sound like they come from Tupelo.”

Natalie practically jumped out of her seat.

“Some of them are from Mississippi.”

When it came to rock ’n’ roll, she obviously knew what she was talking about. The table went suddenly silent until Ezra leaned forward and roared over the din in the room.

“How ’bout we hit my mama’s place and dig her race records.”

Natalie glanced at her wristwatch.

“I don’t know. I’m a workin’ girl.”

Norman’s ears perked up.

“You workin’?” He sounded incredulous. “You don’t seem the type.”

“Yeah, I’m a little shop girl. You heard of us? Nine to five Monday to Saturday. Pays the bills.”

On the street outside the Blackhawk, with the neon sign glowing in the dark, Ezra stood on the sidewalk and tried to hail a Yellow cab. First one driver and then another switched off the light on the roof and accelerated when Ezra came into view, a dark shadow outlined by the streetlight.

“Off duty my ass. Fucking cracker oughta go back to Johannesburg.”

Ah, finally, Norman thought, he’s expressing his true feelings.