The sea around Antarctica sounds otherworldly, full of the trill of penguins, the gulps and rumbles of seals and the rubbery bumps of glaciers hitting up against each other. The sound of a sunrise at Sugarloaf State Park near Kenwood, on the other hand, is more familiar; even without seeing the sunrise, the singing birds sound like they are welcoming in the new day. In a rainforest in Indonesia, the birds sound spooky as they echo in the distance over the steady quaver of insects.

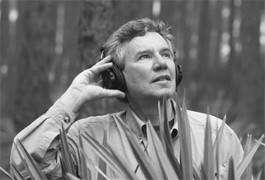

These are some of the recordings by Sonoman Bernie Krause, a specialist in bio-acoustics who has been recording natural sounds all over the globe for the last 40 years. He owns the largest private collection of these biological symphonies in the world–more than 3,500 hours of it.

Now, his company, Wild Sanctuary, in Glen Ellen is working with Google Maps and Google Earth to allow people to hear sounds from anywhere in the world.

Google Maps is a website that lets users plot out points on a map. Google Earth is a 3D globe that uses satellite imagery and aerial photography to let users zoom close up to any part of the world. With Krause’s sound layering technology, people will not only be able to look at other parts of the globe, they would be able to hear them, too.

“It’s almost scary how Google Earth can evoke the physicality of a place,” says Jim Cummings, executive director of the Acoustic Ecology Institute in New Mexico. “To add an overlay of the voice of a place makes it nearly palpable. My hope is that the sound layer will open people up to the ways different habitats connect to each other.”

So far, Krause has developed a beta version of the layer, which can be tried out at www.wildsanctuary.com. Krause does not yet have an official agreement with Google on the project, although he has their permission to develop his content. If it proves successful, Google may invest in adding a more in-depth sound layer to Google Earth and Google Maps.

“We have no paper contract with them, no formal agreement,” Krause says. “If what we’re doing proves itself and there is visitor interest in this particular component, Google may spend the time and effort to develop the layer to support the audio.”

Krause is also planning to add historical recordings of areas to show how they have changed over time, in part to demonstrate the impact of human behavior on the environment. The soundscape is as much an indicator of environmental damage as the landscape.

“You can record an area for a long period of time and hear the human impact on those environments,” says Krause. “You can hear the difference in an area where there is a lot of selective logging, like the Amazon rainforests, or the before and after of pollution on places like a coral reef.”

Sound can even reveal changes in an area that sight cannot. Take Lincoln Meadow near Truckee, which has been surrounded by logging for the last 15 years. Although it looks roughly the same today as it did before the logging started, the difference in sound is dramatic. Krause’s recording of Lincoln Meadow from 1988 is full of birdcalls and insects. Some 15 years later, all you can hear is water running. The difference shows what the eye does not.

“Through acoustics, you can show how healthy a habitat is,” says Krause. “It’s partly instinctive, but if you really want to crunch numbers, you can do some scientific comparisons having to do with density and diversity. It really does help.”

Scientists are just starting to understand how sound pollution affects nature. One growing concern is how noisy the ocean has become. With the Navy using sonar and all the sounds related to oil and gas exploration, the overall background noise in the ocean is doubling roughly every 20 to 30 years. And while some experts don’t think that it is anything to worry about, others believe the change is affecting sea life. Many creatures use sound to communicate and find their homes–especially whales.

“Whales use sound to navigate,” says Cummings. “They need to be able to hear faint sound. When background noise rises even modestly, it shrinks their communication range significantly. There is a lot of concern among biologists that we are changing the social dynamics of the whales this way.”

It’s not just the environment that’s suffering. As the soundscape get increasingly shrill, humans suffer too, often without realizing it. Most people learn to ignore the constant sounds around them–the TV, the traffic, the phone, the mp3 player. Tuning this noise out may become a matter of habit, but it still increases stress and disturbs our sense of peace.

This is especially true in the United States. North America, Krause says, is the noisiest place on the globe. In his 40 years of collecting sound, some 40 percent of the natural soundscapes he has recorded have gone extinct, replaced by more urban sounds.

Krause hopes is that by adding soundscapes to Google Earth, people will become more aware of the noises around them, and may even seek out some of the natural sounds that we can so easily ignore.

“All the noise we create obliterates the sounds that can really make us feel good about being here,” Krause says. “All the insects, birds and mammals–things that are life-supporting instead of stress-creating.

“No culture is as noisy as North America, and no culture has as many prescriptions for Prozac as North America.”

Listen up at www.wildsanctuary.com.