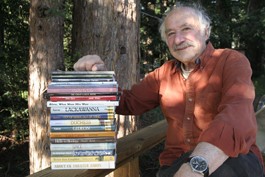

Knowing Chester Aaron has been one of the genuine pleasures of my life, one I surely share with dozens of folks around the country. The charismatic Occidental writer and garlic king has lived an extraordinary life and, at 85, remains one of our best writers and storytellers.

I met Aaron in the early ’70s at St. Mary’s College in Moraga. It was his first year of teaching college and he was closing in on 50. Not long before, a New York publisher had released his marvelous first novel, About Us, the semi-autobiographical tale of a Jewish family in a western Pennsylvania mining town.

Aaron grew up scrapping in such a family. He fought in the streets and had numerous Golden Gloves bouts. In his early 20s, Aaron was a machine-gunner with the 20th Armored Division, fighting through Germany and participating in the liberation of the concentration camp of Dachau.

Following the war and his military discharge in Los Angeles, Aaron attended UCLA and began writing. The rich cultural climate of postwar L.A. was studded with luminaries recently flushed out of Europe. Aaron got to know Bertolt Brecht, Christopher Isherwood and the powerful activist poet Thomas McGrath, who famously stood up to the House Un-American Activities Committee. He even met Greta Garbo in the kitchen of a house filled with Hollywood intellectuals. After he replied to a question about his age, Garbo muttered, “Too young.”

In the ’60s, Aaron moved to Northern California, where he worked at Alta Bates Hospital in Berkeley as an X-ray technician, a job he was fired from in the early ’70s for his exposé of the overradiation of African Americans in U.S. hospitals.

In 1999, Aaron retired as professor emeritus from St. Mary’s College, where he’d taught for 25 years. By then, he’d published more than a dozen books and was growing more than 90 varieties of garlic at his Occidental home.

After the publication of his book Garlic Is Life, Aaron became a legend in the world of the stinking rose, trading stories and rare cuttings with growers from around the world. He also had the bittersweet experience of seeing his gardening books far outsell his literary work.

At present, Aaron has become obsessed with memories of the concentration camp at Dachau. He is no longer able to write about much else. For decades, he had effectively repressed the experience. But in 2004, he unearthed long-stored photographs he had taken in Dachau of freight cars filled with bodies and parts of bodies.

Since that day, Aaron has been working on a collection of 10 stories to be titled After Dachau. Aaron hopes to finish the collection in 2009.

In the story “Past Is Present,” 83-year-old Abe Kahn shoots at wild turkeys that have been eating his crops:

One of the five has dropped just beyond Box 2 and lies on the ground, flopping about, trying desperately to scream for help but only coughing. Coughing and gagging. Flopping and coughing and gagging. Abe, standing over the body, sees not the dying turkey but the dying German soldier coughing and gagging and flopping about. The dying German soldier trying to call to his comrades for help.

“You son of a bitch.”

Is he talking to the turkey or to the young blue-eyed German soldier lying at his feet?

Looking down at the purple head and the almost beautiful black-red feathered wings, Abe hears one last coughing gasp. He waits and watches with a sense of mission-accomplished as the black-red wings that have been beating rapidly beat slowly, then stop beating.

Continuing to watch, he continues to see not the turkey but the German soldier . . . 19 years old? 20? . . . gray-green jacket pouring blood, black bucket helmet in the mud near the blond head.

The 83-year-old Abe Kahn observes the 19- or 20-year-old German soldier the 20-year-old Abe has shot in the chest. The soldier closes and opens his fingers and jerks his arms as if trying one last time to reach for something he hopes to take with him on the long dark journey he knows he is about to begin.

Chester Aaron sleeps fitfully these days, often rising in the middle of the night to work on one of his Dachau stories, as his past closes in on his present.

Novelist Bart Schneider was the founding editor of ‘Hungry Mind Review’ and ‘Speakeasy Magazine.’ His latest novel is ‘The Man in the Blizzard.’ Lit Life is a new biweekly feature. You can contact Bart at [ mailto:li*****@******an.com” data-original-string=”1giH2ovuPOMob6tM8P3OIA==06aUOK+zX/DFyn+hRCiBzj7WmIUaPWmY1lpc288EWEx8AQ1xg/XEplKzl0p0bdtCcKi6h/iL/9/OPaqUrPGTBB86Vb5JV+oYhRYSg2S4IQl2lc=” title=”This contact has been encoded by Anti-Spam by CleanTalk. Click to decode. To finish the decoding make sure that JavaScript is enabled in your browser. ]li*****@******an.com.

Museums and gallery notes.

Reviews of new book releases.

Reviews and previews of new plays, operas and symphony performances.

Reviews and previews of new dance performances and events.