Quentin Tarantino uses the ’50s version of the Columbia lady in his pre-titles to Django Unchained, but the film exceeds both the length and bounds of the Western movie/ slaveploitationers Tarantino is raiding, whether low and grimy (like 1971’s Goodbye Uncle Tom) or high-budget and De Laurentiis–produced (like 1975’s Mandingo).

Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) is a dentist-turned-gunslinger, practicing his trade at the end of the 1850s. In Texas, he liberates the slave Django (Jamie Foxx) for the practical reason that the shackled man can lead him to a trio of criminals hiding on a plantation. Django takes to the killing work with ease—”Shootin’ white folks, what’s not to like?”—and has a mission of his own: his wife (Kerry Washington) has been sold down the river by a cruel master (Bruce Dern). She’s languishing on “the fourth biggest plantation in Mississippi,” a place known as Candyland, operated by the disgusting Calvin J. Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio). To infiltrate the place, Django will pose as a free black slaveholder seeking to buy bare-knuckle-fighting Mandingos.

Waltz’s Dr. King (an odd joke, considering what the real MLK thought of violence) delivers speeches that are a handsome apology for the potential anti-Germanness of Inglourious Basterds. Schultz, practically a one-man Goethe Society, reaches for his culture as often as he reaches for his revolver, and Foxx’s heavyweight glare is tempered with yearning.

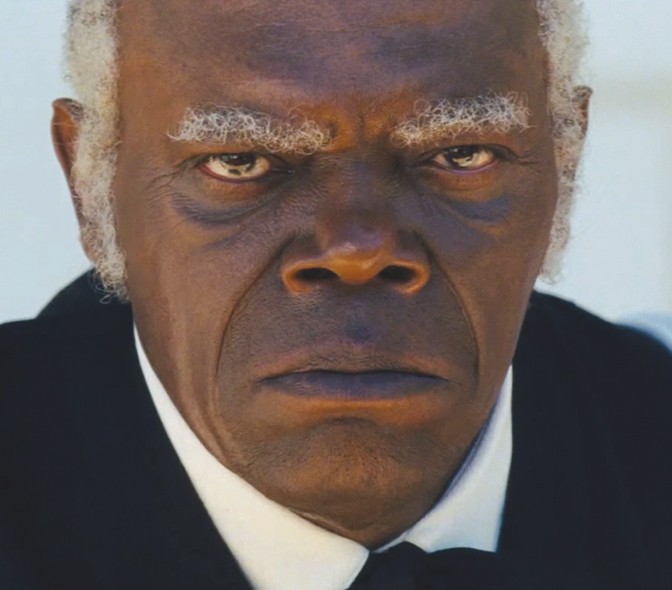

But it’s Samuel L. Jackson who catalyzes everything Tarantino has to say about slavery. Jackson is the second-highest grossing actor of all time by some measures. Much of what filled his wallet, he earned with “bad motherfucker” parts. Jackson is made for Candyland.

Every white liberal who flinches at seeing an Uncle Ben rice box will get that sting watching Jackson as “Stephen,” the house man at Candyland. The role of “porch negro” would be a deal-breaker for most black actors, particularly in a movie that’s primarily a comedy, so it’s a tribute to Jackson’s taste for risk-taking that he went for it.

It’s one thing to imagine being whipped and branded—some people do that kind of thing for fun—but what Jackson gets at is a lot dirtier, eerier and harder to countenance. He shows us the corrosion of a man who has to pretend to be a pet, wriggling with gratitude, putting on a show of human warpage that only white people grown stupid and lazy from the slaveholder’s life wouldn’t suss out.

Jackson demonstrates the rage that everyone loves, with a counterbalance of implosion, as he stumps around pretending to be kindly and dotty. If it’s foolery, it’s the kind of fooling that goes on in King Lear. This is the performance of Jackson’s career.

‘Django Unchained’ opens in wide release on Christmas Day.