Anthony Tate had been homeless in states and cities all across America, adrift for decades under the unrelenting thumb of post-traumatic stress disorder from his service in Vietnam, when he arrived in the Bay Area three years ago for yet another chance to get it right.

Before long, the veteran had found himself a place to live with the help of a local veterans organization. With the stability came a purpose, and a profound one at that: Tate devoted himself to trying to make sure veterans from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan didn’t wind up on the streets as he did.

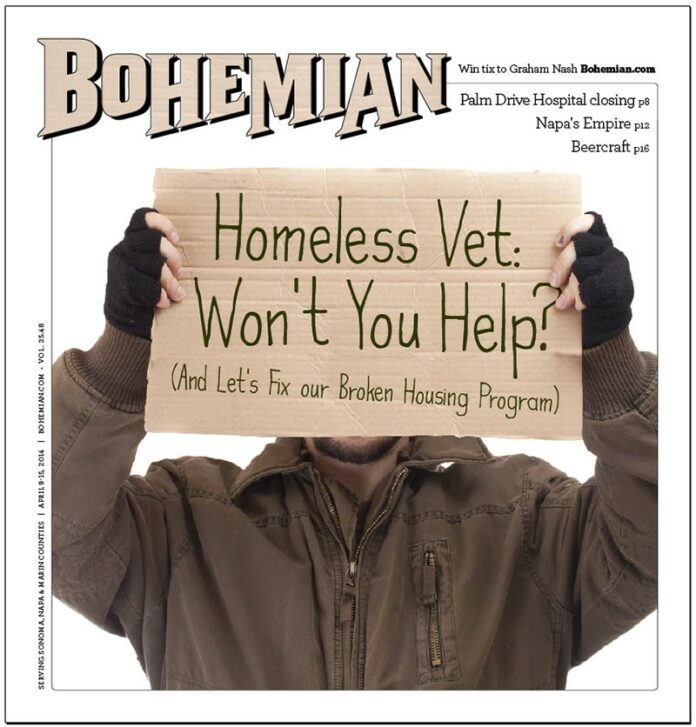

Tate’s efforts on behalf of homeless vets comes as Californians will be asked, on June 3, to vote on Proposition 41, the Veterans Housing and Homeless Prevention Bond Act of 2014. The proposition would jump-start a veterans housing program that could see numerous multifamily supportive housing units for veterans sprout up throughout the North Bay in coming years.

“I got the support and the help I needed,” says Tate, who now lives in Santa Rosa’s Bethlemem Towers, and has no intention of leaving. The stability gave Tate the grounding necessary to deal with the ongoing fallout from his deployment. And then he could start the work of helping others.

Tate was a desk-bound clerk in the storied 82nd Airborne Division when he was deployed to Vietnam in 1969. It was a big surprise, he says, and one that took him 40 years to get over. “They gave me an M16, a clip of ammo, a canteen, and said, ‘Stand over there,'” he recalls.

“That’s when reality set in. They told me, if you survive 365 days, you can go home.”

Tate survived.

He was 17 when he went to Vietnam and 19 when he returned to America. He subsequently bounced around for decades and ticks off the states he passed through over the decades: Maryland, Ohio, Michigan, Colorado, Mississippi, Illinois, Indiana and elsewhere.

No matter where he was, Tate says he was haunted by the sound of chopper rotors whenever he heard civilian helicopters stateside. “It kept taking me back,” he says. When he arrived in San Francisco, he says “Little Saigon” was off limits because of the PTSD triggers there.

Nowadays, Tate and other vets set up shop outside the Department of Veterans Affairs building in Santa Rosa on weekday mornings to dispense coffee and pastries to veterans. He was hired as a volunteer with the Sonoma Housing Authority board, and he sells baseball caps affixed with military logos to raise money for a local veteran who was grievously injured by an improvised explosive device.

“Never again will one generation of veterans abandon another,” says Tate as he greets a cross-generational group of vets coming in and out of the VA building on Airport Boulevard. His first piece of advice to returning veterans who need help: “Don’t wait 40 years to get it,” he says with a slight laugh.

The second: “The first challenge is housing.”

The news is filled with numbing reports about the challenges facing returning vets—challenges that haven’t abated, even as the post-9-11 wars have wound down. Ghastly rates of suicide and post-traumatic stress disorder among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans remain in the headlines, along with the usual and unfortunate accompaniments to mental illness: alcoholism and drug abuse, crime and violence, family problems and homelessness.

“We work hard to say, ‘Look man, you need help,'” says Tate. “These guys are trained to be independent, so we have to say, ‘Hey, that pride—put it in your back pocket. You need help.'”

But in a tight economy where the concept of “affordable housing” is less an achievable goal for many than a mocking oxymoron, Iraq and Afghanistan veterans have slipped into homelessness even faster than their fellow veterans from the Vietnam conflict. “There have been lots of suicides,” Tate says sadly, “and we want to stop that cycle—and we want to stop the homelessness cycle.”

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, about 20 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans take their own life every day. About 63,000 are homeless.

Tate is at the tip of a new post-war effort, spearheaded by President Barack Obama, to end homelessness among veterans by the end of 2015. It’s a laudable goal and a fight worth having. “It’s unrealistic,” says Tate, “but it is offered.”

Even if the country’s most recent wars aren’t popular among many Americans—especially the invasion of Iraq—the soldiers themselves have not faced the degree of animosity greeted upon those returning from Vietnam, notes Tate, an African American who grew up in yet another war zone, the notorious Chicago housing projects.

“We knew not to expect anything when we got home,” he recalls, “but these guys—they are heroes when they come back.”

Tate says doing this work with returning Iraq and Afghanistan vets is how he “started to feel proud to be a Vietnam veteran.”

California has set the stage to do its part for homeless vets by retooling a housing program for them.

The state’s putting a referendum measure on the June ballot that would, according to the Sacramento Legislative Analyst’s Office, “sell $600 million in general obligation bonds to fund affordable multifamily housing for low-income and homeless veterans,” from an undersubscribed $1 billion veterans home-loan program. The $600 million would be used to build housing more in line with the needs of modern-day veterans, many of whom are single, male and afflicted with one war-related disorder or another.

The original program was created decades ago and stipulates that the loans are for family homes or farms—$400 million would remain untouched for these loans.

California voters have to agree to do it, which raises the NIMBY-ism issue, always at hand in the North Bay.

If voters approve it, the referendum would pave the way for building housing for veterans that would include on-site social service programs, the hallmark of the “supportive housing” movement, which takes a page from addiction-therapy models when it strives to “meet people where they are,” even if where they are is poor, addicted and otherwise homeless.

The question for North Bay progressives and others is a thorny one that will play out at the ballot box: Will public support for Iraq and Afghanistan veterans translate into public support for housing that’s not the typical state-run facility for vets? Will support for veterans eclipse concerns about property values?

“We have to start somewhere,” says Tate with a chuckle as he grapples the question. “We’ve had developers who wanted to rehab a home for six or seven vets,” he says. Those developers were told, “You can’t do that here.”

The traditional model for veterans services in California has been provided at a handful of state-run facilities around the state.

One such facility in the North Bay has come under intense fire by state auditors. A recent report from the California auditor blasted the Yountville Veterans Home in Napa County for spending over $650,000 in taxpayer money on high-end frivolities of little use to troubled returning veterans; Yountville’s now-former top brass, for example, approved the construction of recreational zip-lines and an in-house tavern.

All returning veterans deserve respect (and many would argue even a fully stocked bar), but the Yountville audit highlighted a major disconnect in state-provided services for veterans: the state veterans facilities around California do not means-test veterans, so returning wounded warriors of limited means aren’t given special consideration when they come on hard times.

For those troubled men, a highway underpass in Napa Valley or a tucked-away hillside in Marin may have to do for the night—or for longer.

“We’re not going to bring everyone out of the woods, the creeks, the railroad tracks,” says Tate. As he speaks, a man emerges from the rear of the Santa Rosa VA building and gives a wave of hello to Tate.

“He’s a wilderness guy,” says Tate. “He lives out behind the VA.”

The man gets a cup of coffee and disappears.