It’s a sunny Saturday morning in July at Lawson’s Landing at Dillon Beach, achingly beautiful and breezy, as Bob Bedsworth ambles down a sandy path, a bright-red five-gallon bucket of spent horseneck clamshells in hand.

He has just finished giving a shucking lesson to one of his grandkids from the back deck of his trailer at the campsite. It’s a scene that’s likely been repeated hundreds, thousands of times at this popular campground.

Bedsworth is retired U.S. Air Force, has a home in Elk Grove and spends five months a year in his trailer at Lawson’s Landing, from May through September. He’s been coming here for 34 years. But those days are coming to an end, as Lawson’s faces an uncertain future.

Bedsworth owns one of the 200-odd semi-permanent camper-trailers perched along the edge of Tomales Bay. They’ll all be gone by this time next year. That move is a key piece of a long-in-the-making deal struck in 2011 between Lawson’s Landing and the California Coastal Commission to keep Lawson’s open.

But ask Lawson’s owners and they’ll tell you that, because of financial and regulatory challenges, staying open is by no means assured.

Bedsworth recalls the clamming, the abalone diving and the general good times he’s had over the decades he’s been coming to this rather remote and free-wheeling campground, where the cattle once ran free on an adjoining ranch also owned by the Lawson family.

“Where else can you find a place on the bay that’s reasonably priced and where you can bring the kids, the grandkids,” says Bedsworth. “I’ll miss that.”

Under new rules designed to save the endangered red-legged frogs, famous Tomales dunes and snowy plovers, Lawson’s will have to abide by state laws that restrict people from coastal camping for more than two straight weeks at a time.

The idea is to give other people a shot at camping at the location and to protect sensitive habitat. But once those camper-trailers are gone, Lawson’s owners say they will have to provide access to a more well-heeled crowd of luxe campers as part of its plan to stay afloat. And that may not be enough, the owners fear.

Bedsworth peers over the top of his rectangular sunglasses and says with a soft smile, “I’d just as soon it not happen. I think it’s stupid.”

He heads off to dump his bucket of clamshells into the sun-dappled bay.

CLAMS AND FREE AIR CONDITIONING

Lawson’s Landing has been a family business in northwestern-most Marin County since the late 1950s. The family has owned the land, which until recently comprised some 1,000 acres, since the 1920s. The camping scene has historically been dominated by blue collar and middle-class folks from the Sacramento Valley.

“They come for the free air-conditioning,” says Lawson’s Landing co-owner Carl “Willy” Vogler.

The campground first came into the crosshairs of Marin County environmentalists in 1962. None of the moving parts that had kept the revenue flowing to the Lawson’s—a sand quarry (now defunct), the cattle ranch (still operating), the camping—had operated with a use permit from the county.

The boat livery is still operating, which is a rare sight at marinas these days because of liability concerns. You can rent an aluminum boat (the motor’s extra) and head out to the bay for the day. There’s also a boat-repair shop attached to the fishing and retail operation.

The family has been trying to get use permits since before the advent of the Marin County Local Coastal Plan in 1980, but to no avail, say Lawson family members. “We’ve been working with, and sometimes against, the agencies, trying to get things permitted,” Vogler says.

The coastal plan is essentially the local reflection of mandates contained in the state Coastal Act of 1976 that created the California Coastal Commission.

The campground’s footprint has shrunk from 100 to about 20 acres, and you can feel that the squeeze is on. There are a few abandoned public restrooms that tell of the downsizing. Tent campers are now slotted into small patches of grass, and everyone seems to be right on top of one another.

The owners returned 465 acres of campsites back to wetlands as part of an ongoing settlement arrangement with the coastal commission (a “consent cease and desist”), and in exchange were given the green-light to grow-out the tent camping in less sensitive areas. That hasn’t happened yet.

“There’s work to be done,” says Vogler. “It will take tractors and time,” and the latter is in short supply in the summer.

The 465 acres comprised the most eco-sensitive parts of the Lawson’s holdings, and they put the acreage into a permanent conservation easement with the federal Natural Resource Conservation Service for

$5 million.

Meanwhile, the family hasn’t been able to move on the part of the redevelopment plan that would allow them to put in new camping areas in other parts of their land.

The Lawsons now say that a much-anticipated coastal commission scientific survey (which, they stress, they were not required to do) has been so long in coming that it’s handcuffed them from making the necessary changes that would keep them in business.

The survey is a necessary precondition for the family to start dealing with critically needed wastewater infrastructure. New bathrooms and shower facilities are part of the deal, among other upgrades.

The family says it can see a viable business on the other side of this complex and multimillion dollar transition—but getting from here to there without going out of business in the process? That’s another story.

[page]

“I’m extremely nervous,” says Vogler. “This is supposed to remain a place for low-cost coastal access, and I want to keep it that way.”

While he sees a business after the transition, “it’s paying off the other stuff to get there that is the terrifying part. The trick is to make the income meet the out-go.”

Marin County supervisor Steve Kinsey is more optimistic.

“I believe that Lawson’s Landing has several more generations of opportunity for visitors to come,” says Kinsey, who has dual role here in his additional capacity as a commissioner with the California Coastal Commission. Kinsey notes that the family has a “very viable coastal development permit that they can work with.”

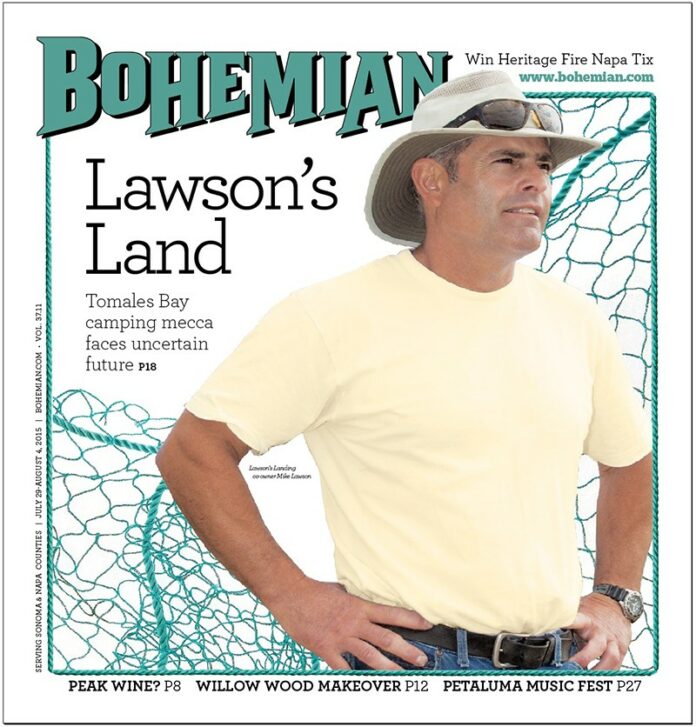

Kinsey was, however, surprised to hear the extent of the worry expressed by Vogler and co-owner Mike Lawson over staying in business.

“I personally think they should be talking to me if they think it is that serious,” he says. “The last thing we want to do is to eliminate the largest coastal camping opportunity in Northern California. That’s not the intention, and there would be ways that it could possibly be addressed. I am determined to help them not go out of business.”

Kinsey says that he had been an early proponent of seeing the “historic trailers prevail,” but agrees with the ruling consensus that those folks had to share the wealth with other campers.

Catherine Caufield is the former executive director of the West Marin Environmental Action Committee, a nonprofit that was a major driving force for the changes afoot at Lawson’s. She agrees that the slow-roll on the scientific study has created “a bit of a bottleneck, because it just took time to do a good job.”

Caufield credits the family with the changes that they have made to address the environmental concerns her organization highlighted. “I believe that Mike [Lawson] and Willy want to do the right thing,” she says, “and we’re always there to encourage them just a little bit more.”

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking on the camper-trailers, which have provided a backbone of rental income to the owners for decades. The 2011 deal gave those trailer owners a five-year window to get out. That’s a hard deadline, and it’s coming July 13, 2016.

The coastal commission has two general mandates: Keep the coast clear of excessive development that would negatively impact the environment; and ensure that the California coastline is accessible to everyone, and especially those of lesser means.

Lawson’s and Marin County struck a deal to keep the business going in 2008. The West Marin Environmental Action Committee challenged that agreement, and that’s when the issue jumped from the county’s in-box to the coastal commission.

“The coastal commission was supposed to shut us down,” Vogler recalls. They entered into a “consent cease and desist” with the agency as part of the agreement to remove the trailers. “They chose not to enforce the ‘cease’ part as long as we kept moving down the road, making the improvements,” he says.

“What the coastal commission did—right, wrong or indifferent—was they offered a compromise that PO’d the environmentalists, the NIMBY people and us. I’d call it a good compromise where people wind up basically being equally unhappy. Everybody was more or less disappointed with it.”

HARD TIMES?

“This was supposed to be a fast-track deal,” says Mike Lawson. “The five-year period is coming to an end, and we have no way of replacing our business in a quick, business-like time frame with something else. Either the coastal commission is going to allow us to keep the business afloat for another year or two, or we are going to be facing some really hard times. When the trailers go away, we have to replace that revenue, but we can’t replace that with low-cost, overnight camping.”

Lawson says that survivability may now hinge on a new wastewater system that’s part of the purview of the coastal commission study currently underway. The family, he says, had submitted a preliminary proposal to the commission and Marin County to get a proper use permit for the proposed build-out, and it was approved—but only preliminarily.

“We think we have a strong argument for redeveloping a formerly developed area, but we’re still waiting to hear from the scientific review panel,” says Lawson.

One idea under exploration would put the land into the purview of the California Coastal Conservancy. In that scenario, the state agency would partner with the Lawsons, loan them the money to stay afloat and then collect the loan back at a low interest rate.

“But money is getting hard to find,” Lawson says. “Our planner is trying to work with some of those people and get something done here.”

GONE FISHING

To say that it’s a bustling day at Lawson’s Landing is to say that people have been mildly interested in the recent goings-on on Pluto.

And we’re in a far-off place in the Marin County galaxy here, in the northern reaches where Tomales Bay spills out into the Pacific Ocean by way of Bodega Bay. Today, the place is positively bopping with mid-summer recreation, and it’s a hoot to behold.

On this particular Saturday morning, Tomales Bay is coming right off an ultra-low “clam tide,” and the clam diggers were out there all morning. Vogler says some of those clam diggers are a little less welcome than others. Lawson’s has been victimized by its own popularity.

“We started to attract other clientele from the Bay Area that didn’t have any concern for conservation for saving some for next year,” says Vogler.

A couple of front-loaders stand at the ready to “splash” boats from their trailers into the bay. The fishing pier that sticks out into Tomales Bay is loaded with crabbers and fishers; there are buckets full of red crabs, people jigging little fry for use as live bait. A lone dude with a surf-fishing rig sits in a beach chair way out on a long sand spit at the edge of the bay, waiting for a bite.

As if on cue, a woman points into the bay to a spot that had earlier been loaded with clammers. Gesticulating wildly and yelling at no one in particular, she exclaims, “Is the game warden around today? Can you please save some for our grandchildren?”

[page]

The woman then strikes up a conversation with an elderly woman in a big floppy sun hat seated on a bench. They begin shouting things at and past each other about having relatives who arrived at Ellis Island, back when, you know, immigration was immigration.

“Trump was absolutely right!” one of them exclaims.

“They want Sharia law in Sacramento, there’s going to be a problem!” exclaims the other.

Well . . . umm . . . errr . . .

How about we take a stroll among those cool trailers! While it’s still going, the trailer community offers a fascinating glimpse into a particular variety of coastal Americana. There are numerous varieties, but the tin-can aluminum rectangles that jut out at rakish angles—those are all over the place and stand out; they are the characteristic Spartan Trailer design from the 1940s and ’50s, when America again took to recreational pursuits after the Great Depression and an even greater world war. The overall feel of the joint is exquisitely ramshackle, but not down-at-the-heel.

Lawson’s Landing is akin to the all-but-vanished American drive-in movie theater, a last vestige of a bygone era centered on leisure and motion—and geared toward working and middle-class families.

And there’s no question that the trailer owners are holding out for that last briny breeze, the end of the endless summer in these salt-encrusted and well-worn domiciles. So far it appears that nobody’s yet left the premises.

Meanwhile, there are decades of accrued character and memories to contemplate and enjoy: glass Japanese mooring balls in the windows of a few trailers, signage with proud declarations that this is our summer home. As a sign of things to come, there are “For Sale” signs everywhere. There’s also a bunch of golf carts, a “Grateful Dead Way” street sign, variously constructed deckage and driftwood bric-a-brac, a living museum of accumulated flotsam and jetsam.

The rent is cheap, $400 to $500 a month, and the view is world-class, looking across to the untrammeled Point Reyes National Seashore wilderness area.

Jerry Knedel is cleaning his boat near his trailer after a morning fishing trip, and he pulls a couple of dripping lingcod and a salmon from his fish box and tosses them to a friend. Knedel and family have been coming here for 56 years, and he speaks of possible scenarios where a hotel like the Ritz-Carlton buys up the land from the Lawson’s, builds a fancy resort, and just like that, it’s all over for the working man. Knedel just can’t see how Lawson’s can swing this state-mandated transition.

The family says it plans to use the freed-up space for non-permanent trailers, which Knedel describes as “1 percent campers,” big rigs in need of multiple hookups, which the Lawsons will install once the long-term trailers are gone.

Knedel says, and Lawson confirms, that the rents have gone up in large measure to help the Lawson’s pay their lawyers and consultants. He recalls that the rent was $19 a month when his family started coming here.

“The spikes in rent,” Knedel says, “were the result of lawsuits to oppose Marin County, the coastal commission and the Marin County supervisors who have drummed up multiple bogus offenses” to drive the business to a brink of unsustainability.

But the halibut bite’s been good, he adds.

Meanwhile, Vogler is in his office in the fishing station, chock-a-block with maps and memorabilia, and there’s a toddler rocking away in one of those egg-shaped thingamabobs. Vogler’s kids are out front tending the retail shack—get your bait, get your ice cream bars here, sit on the bench out in front and take

it all in, xenophobic outbursts

and all.

As he describes the various twists and turns along the way to a final deal with the state, a Lawson’s worker comes in and tells him that a boater has had a problem—his prop was fouled by a fallen marker that was used to indicate a nearby sandbar.

The exchange gives a rich insight into how to properly run a family business that’s geared toward families. “Give him a new prop,” says Vogler, arms akimbo as he laughs, “but he’s not getting another one after this!”

END OF AN ERA

Mike Pfeifle and Robert Roth are friends from Lodi who’ve just returned from a spearfishing adventure out in Tomales Bay. Their quarry was halibut, and Roth says he speared a nice one that morning—but nothing on the order of the 32 pounder he once lanced here.

The men are hanging around in front of a rare sight along the seawall and trailer area: an abandoned trailer that’s all torn-up inside, no doors or windows, totally junked-out.

Pfeifle owns a trailer over on lot A-13 and Roth, with a hearty chuckle, describes himself as his free-loading friend. Roth says he brought two granola bars with him from Lodi but hadn’t yet eaten them: there’s a lot of communal food-sharing going on among the trailer owners.

Roth says he’s been coming here for 30 years but has had a permanent camper here only for the last eight. Roth is a bus dispatcher back home; Pfeifle works in hazardous waste, he says.

Pfeifle says he’s gotten used to the idea that an era is coming to an end, and he’ll keep coming out here even after his trailer’s gone. He’ll keep spearing and gigging halibut, and diving for abalone, and he’ll keep telling the story around the campfire about that time the great white shark

showed up.

He’s going to hold out through the year. “I’m pulling mine out in January,” Pfeifle says, still wearing the wetsuit from the morning spearfishing trip. “It’s been on the horizon,” he says. “I’ve gotten used to the idea.”

Roth leans against the abandoned trailer and revels in what he calls the great appeal of Lawson’s Landing. “The beauty here is the pride that people have in these salted, sometimes rusted trailers,” he says, “the uniqueness that you continually see here.” He speaks of the blending of people, the unforced multiculturalism, and says the resort functions as a sort of “great equalizer,” where people of all races and persuasions gather.

There are pot-luck dinners after everyone’s come back from their fishing trips, he says. “It’s all about the tribal experience, the coming together after the fish-hunting. That’s going away, and that is unfortunate for the next generation.”