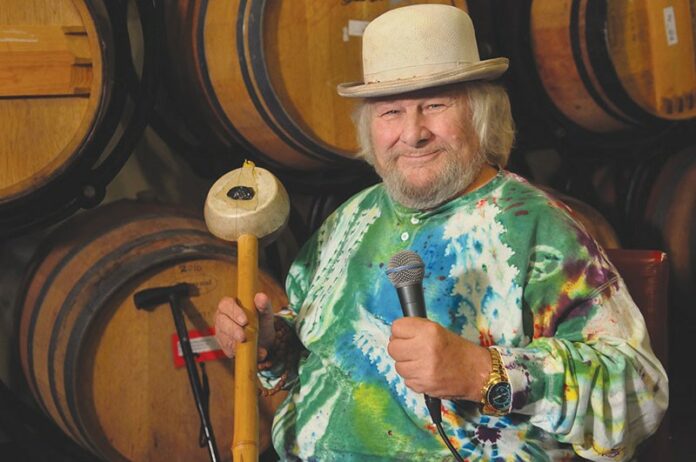

Poet, activist, clown, ice cream flavor—Wavy Gravy has been many things. An icon of the counterculture movement since the 1960s, Wavy Gravy, born Hugh Romney on May 15, 1936, turns 80 this month.

To celebrate, he’s throwing two festive birthday parties. On May 15, Gravy welcomes Doobie Decibel System, Steve Kimock and others to the Sweetwater Music Hall in Mill Valley. On

May 22, Gravy hosts a blowout bash with headliners Yonder Mountain String Band, Steve Earle, John Popper and many others at the SOMO Village Event Center in Rohnert Park.

Both shows also act as benefit fundraisers for Gravy’s Seva Foundation, an organization that restores eyesight to millions of people around the world through cataract surgery, in addition to other health programs.

Though he’s entering octogenarian territory and doesn’t get around as spryly as he used to, Wavy Gravy says he still feels like a teenager.

“I think I approach [life] one breath at a time, and I try to be enthusiastic with each breath,” he says from his home in Berkeley.

Looking back on a life spent spreading messages of peace and love, Gravy’s philosophy boils down to a line he took from author Ken Kesey. “Always put your good where it will do the most,” he says. “Where my good will do the most is Seva and Camp Winnarainbow,” his ongoing circus summer camp.

Gravy’s professional journey started as a beat poet in Boston in the late 1950s, putting together jazz and poetry shows in the basement of a local bar. He soon moved to New York City and began reading in Greenwich Village coffee houses, finally landing at the famous Gaslight Cafe, where he he started hosting folk-music nights.

“God, I remember when [Bob] Dylan came into the Gaslight, he was wearing Woody Guthrie’s underwear,” says Gravy. “He asked me if he could go on. I grabbed the mic and said, ‘Here he is, a legend in his own lifetime—what’s your name kid?'” Gravy would end up sharing a room above the Gaslight with Dylan.

By the mid 1960s, Gravy and his Hog Farm collective of performers and pranksters were roaming across the country touring and opening shows for acts like Peter, Paul & Mary and Thelonious Monk.

That’s when Gravy’s hippie nature took hold. “I began to realize there was more to the universe than ‘Hey mom, look at me,'” he says. He worked tirelessly to stop the war in Vietnam, and appeared at Woodstock, where he famously said “Good morning, what we have in mind is breakfast in bed for 400,000.”

His adventures and performances range from building moats of Jello around a stage to building playgrounds in Kathmandu and distributing medical supplies to Tibetan refugees.

In 1978, Gravy joined forces with his friend Dr. Larry Brilliant (a leader in the World Health Organization’s smallpox-eradication efforts), spiritual philosopher Ram Dass and others to form the Seva Foundation, which has helped restore sight to millions.

“Eighty percent of the people in the world who are blind don’t need to be blind,” Gravy says. “They could get their sight back for about five bucks an eyeball when we started it. It’s about $50 per eye today. Seva is going towards 4 million people who aren’t bumping into shit anymore.”

The upcoming birthday bashes, both at the Sweetwater and at the SOMO Event Center, will raise money on behalf of Seva. While the Sweetwater show is an intimate celebration, the SOMO concert is a full-scale music festival.

In addition to icons like Steve Earle and John Popper, the daylong concert also features New Riders of the Purple Sage, Achilles Wheel, Dead Winter Carpenters, Grateful Bluegrass Boys, T Sisters and other surprise guests. Food and craft vendors, an art gallery and silent auctions are also part of the fun.

As dear as Seva is to Wavy Gravy, he is equally proud of his work with Camp Winnarainbow, his longtime summer camp located in Mendocino County near Laytonville. The camp teaches circus and theatrical arts, but is at heart a community and a compassion-building enterprise. “We’re creating universal human beings who can deal with anything that comes down the pike,” says Gravy.

“In 20 years, I’ll be 100,” he says. “Methuselah says the first 100 years are the hardest—it’s all downhill from there.”