No one could predict that the internet and social media would turn the spotlight on niche magazines and indie presses. And yet, according to market reports and sources like TheMediaBriefing.com, there’s never been a better time to be a quality publisher. Some say it’s the golden age of small, independent presses and publishing houses that push boundaries while their established colleagues compete for the next big series or bestseller.

Alternative magazines, following in the footsteps of Kinfolk and Lucky Peach, are also blossoming. Sometimes funded by crowdsourcing sites like Kickstarter, and often artfully designed, they provide an alternative to the media cycle, in which “recycling” is a key word. Unlike nationally circulating lifestyle brands, each independent magazine carries a sense of the place, atmosphere and area in which it was created. No wonder niche magazines are increasingly being called “time capsules.”

This is very much the case with the Inverness Almanac, a biannual print publication from West Marin, a region abundant with past niche publications, such as the well-loved Floating Island and Estero journals. With only four volumes since its inception around two years ago, Inverness Almanac managed to set a certain tone. Each cover features an image from nature. Inside, local poetry, art, naturalist essays and inspirational ideas fill the pages.

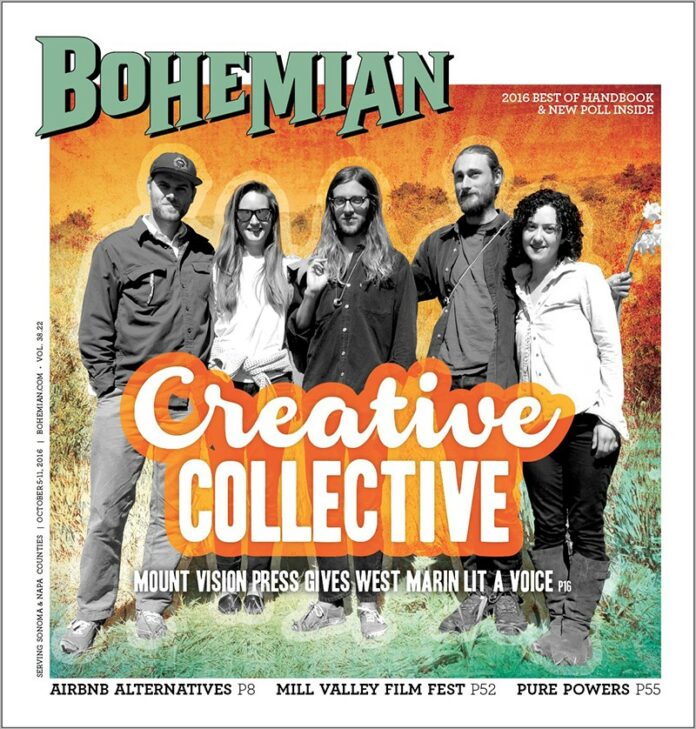

This past month, the team behind the publication put it to rest to focus on their next venture, Mount Vision Press, without really leaving the niche category. The group consists of Jordan Atanat, 34, a woodworker from Point Reyes Station; Katie Eberle, 30, a radio host, DJ and designer from Marshall; Ben Livingston, 28, a farmer and musician from Inverness; Jeremy Harris, 30, a musician from Inverness; and Nina Pick, 33, a poet and editor who travels all over.

The five came together united by their love of West Marin and creativity, and married their individual skills. “We were inspired both by the beauty of West Marin, as well as the rich community of artists, writers and naturalists who live here,” Harris says. “West Marin also has a tradition of local publications such as Floating Island, Tomales Bay Times, Pacific Plate, West Marin Review. Basically, the Inverness Almanac is the publication that we wished to exist. It didn’t, so we decided to create it.”

Ben Livingston remembers the exact conversation that encouraged him to join. “The idea was brought forth around a campfire in Bolinas. Jordan Atanat told me about his vision for a local publication, and I was immediately on board. It was a perfect venue for sharing my experience of the landscape I had grown up in, as well as embarking on a larger creative project than I ever had before.”

While “the dreaming phase flowed pretty easy,” according to Livingston, the practical part was educational, to say the least. The Almanac was printed in Minnesota and Wisconsin, to avoid the high costs of the Bay Area, Harris says.

There were other obstacles, too. “There is the actual making of the book, and then there is interfacing with printers, figuring out business structures, promoting the book, selling the book, planning release parties, on and on,” Livingston says. “Dealing with the business side of things is probably the most difficult for me.”

The first issue came together with help from the local community of artists, writers and artisans. “We put the word out that we’d be collecting submissions to form a publication about our landscape—the place, the people who live here and what gets made here,” Harris says, and submissions poured in. By the fourth volume, which will be released this month, the team “received many more attractive submissions than we had space to include.”

Embodying the West Marin spirit, the Inverness Almanac has been sold in some of the best boutiques and decor stores in the Bay Area and beyond.

[page]

“The spirit of the Almanac communicates universally to anyone who appreciates the natural world and the many ways humans artistically respond to it,” Harris says. “Whether you enjoy the richness of what it tells you or the way it looks on your coffee table, it can satisfy the consumer desire on levels of both function and form.”

Since emerging on the scene, the Almanac has served as part magazine, part calendar, with seasonally based literature and recipes, illustrations, art, a calendar with information regarding tide charts specific to Tomales Bay, solar and lunar cycles and notifications of natural events: plants blooming, birds migrating, ocean currents changing. Now the team is hoping to bring the same natural and cultural sensibilities to publishing.

“Mount Vision Press started as a way to continue and broaden the work of the Almanac,” Livingston says. “We have gotten to know so many talented writers and artists while working on this project, and being able to give their work more space—say, a book—is very exciting.”

According to Livingston, the press, like the Almanac, will gently balance on the local-global scale. “It won’t necessarily focus on West Marin work, but it is a fertile starting ground,” he says. “We intend to publish work that is honest, grounded and contributes to the larger conversation of making sense of life in these times.”

The main reason for discontinuing work on the Almanac, Harris explains, came from a desire to move on to publishing other books, like the first forthcoming Mount Vision Press title Journeywork, a collection of poetry by David Bailey.

“In the Almanac‘s format, we can only showcase so much of someone’s work,” he says. “Being able to give some of the work a book’s worth of space is really valuable.”

Both Livingston and Harris are naturally huge fans of print and limited editions, despite “using computers and the internet every day.” They must be. Why else would a group of young people, with startups and endless app entrepreneurs in close proximity, decide to print something as intricate as the Inverness Almanac or a poetry book? In the fourth and last volume, for example, the readers can find a partial lexicon of Miwok, “an ancient language that was spoken here way before us,” Livingston says. Not your average bit of information, but that seems to be the point.

“The internet has [spawned] the rise of attention-span-deprived, ephemeral media consumption,” Harris says. “What’s popular or interesting one day is forgotten the next. We think smaller publications are trying to resist the tide of everything moving to the internet, to create something meaningful and lasting, something you can hold in your hands and have a relationship with.”

Physical location, in the case of this literary project, has something to do with it. “Marin is in a special position of being in the liminal zone of urban and rural,” Livingston says. “The wilderness of Point Reyes and the influence of a global city nearby can coalesce into something both rooted in the local forest but looking outward into the world at large.”

“There might be a bit of an anticorporate sentiment expressed by some more overtly than others,” Harris adds. “We’re interested in real things made by real people. Also, the Inverness Almanac doesn’t require a battery, doesn’t hit you with blue light before bed and doesn’t advertise to you, which are all very nice things.”

And unlike many technological grand schemes of Silicon Valley, sustaining a publication like the Almanac, aside from the hardships of figuring out Tomales Bay tides and layout, sounds pretty easy. “All it takes is a tiny room and a lot of Pu-erh tea,” Harris says.

“With [Mount Vision Press], as with the Almanac, we’re not as interested in capitalizing on the moment as we are in making things we’ll want to enjoy for, hopefully, decades,” Harris says.