‘Cease fire. Friendlies! I am Pat fucking Tillman, dammit,” shouted former pro football player turned Army Ranger Pat Tillman as a hail of bullets pierced the darkening Afghani sky. “Cease fire! Friendlies! I am Pat fucking Tillman! I am Pat fucking Tillman!”

On patrol in eastern Afghanistan at dusk on April 22, 2004, Tillman and his men hit the dirt, trying to escape swarms of artillery fire coming from the valley below. Tillman detonated a smoke bomb, hoping to signal to his comrades that they were shooting at U.S. troops, known in military parlance as “friendlies.” The firing stopped.

After a moment, Tillman, probably assuming he’d been recognized, stood up. Another barrage of bullets rocketed across the dusty canyon. Three of those bullets shattered Tillman’s skull, ending his life. Other bullets hit his body, with some of the shrapnel becoming embedded in his body armor. An Afghani soldier allied with U.S. forces was also killed, and two other soldiers were injured.

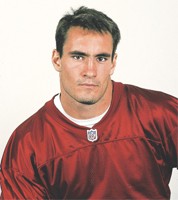

Tillman, lauded by military and government leaders for giving up a multimillion-dollar pro football contract to serve his country, was America’s best-known soldier. A California native, Tillman became the Pac-10 defensive player of the year at Arizona State University and then went pro with the NFL’s Arizona Cardinals.

Even before his death, Tillman was considered a model of self-sacrifice, integrity and decency, not just for his commitment to his country, but for his honesty, candor and conscientiousness. Given his personal integrity, how the U.S. military handled Tillman’s death is that much more appalling.

Kevin Tillman, Pat’s brother, was part of the same 75th Ranger Regiment that Pat served, but the soldiers in his unit didn’t tell him how his brother died. Rangers were ordered not to say a word about the actual circumstances of Pat’s death.

“Immediately after Pat’s death, our family was told that he was shot in the head by the enemy in a fierce firefight outside a narrow canyon,” Kevin Tillman told the Congressional Committee on Oversight and Government Reform during an April 24, 2007, hearing called “Misleading Information from the Battlefield.”

Reading from his brother’s Silver Star citation, referred to in an April 30, 2004, internal Pentagon e-mail as the “Tillman SS game plan,” Kevin Tillman provided an abridged version of what the military had said about his brother’s death. “‘Above the din of battle, Cpl. Tillman was heard issuing fire commands to take the fight to an enemy on the dominating high ground,'” Kevin read. “‘Always leading from the front, Cpl. Tillman aggressively maneuvered his team against the enemy position on a steep slope. As a result of Cpl. Tillman’s effort and heroic action . . . the platoon was able to maneuver through the ambush position . . . without suffering a single casualty.'” Kevin paused.

“This story inspired countless Americans, as intended, [but] there was one small problem with the narrative,” he told the Oversight panel.

“It was utter fiction.”

Idolatry’s Perfect Storm

Kevin Tillman doesn’t believe that the Pentagon’s errors were “missteps” as stated in the Army Inspector General’s report, which was released in late March 2007 and is the most recent of several official inquiries into Pat Tillman’s shooting and its aftermath. The probes, all done by military investigators, have looked into the circumstances of Tillman’s death as well as the false statements about it.

“A terrible tragedy that might have further undermined support for the war in Iraq,” Kevin Tillman says, “was transformed into an inspirational message that served instead to support the . . . wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Los Angeles, chair of the Oversight committee, said at the hearing, “The bare minimum we owe our soldiers and their families is the truth. That didn’t happen for the two most famous soldiers in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. For Jessica Lynch and Pat Tillman, the government violated its most basic responsibility. Sensational details and stories were invented in both cases.”

Waxman noted that “news of [Tillman’s death] flew up the chain of command within days, but the Tillman family was kept in the dark for more than a month. Military officials sat in silence during a nationally televised memorial ceremony highlighting Pat Tillman’s fight against the terrorists. Evidence was destroyed and witness statements were doctored. The Tillman family wants to know how all of this could have happened. And they want to know whether these actions were all just accidents or whether they were deliberate.”

Marin County journalist Norman Solomon, author of the book War Made Easy, agrees with the Tillman family that Pat was used to promote the wars. “This was a perfect storm of idolatry from the Pentagon standpoint: a football hero sacrificing himself for patriotic reasons–it was central casting as far as the Rumsfeld gang was concerned,” he says. “The mythology was so wonderful that the facts were inconvenient and unnecessary.”

What’s astonishing is not just the lengths to which the Army went to create a fictional account, which included changing the testimony of soldiers who witnessed the friendly-fire shooting and the destruction of evidence such as the burning of Tillman’s blood-stained uniform. It’s that this was not an isolated incident, but rather part of a pattern of deception.

In recent months, several other families have pressed the military for details about their loved ones’ deaths, uncovering similar fabrications. These revelations, coming to light after soldiers’ relatives demanded details about their family members’ final hours, may represent a fraction of the military’s effort to conceal friendly-fire or accidental deaths and injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan.

At the April 24, 2007, Oversight hearing, Jessica Lynch–portrayed by the Pentagon in spring 2003 as the “little girl Rambo from the hills of West Virginia who went down fighting”–testified that the story the military told about her was a blatant lie. Lynch never fired a shot when her caravan was ambushed. After being severely wounded, she was kept alive by Iraqi doctors and nurses who donated their blood to replace her own.

Perhaps the most cynical action revealed is that, according to sworn testimony during the Oversight committee’s hearing, Lynch’s “rescue” from the Iraqi hospital was delayed by a day so that the Army could bring in camera crews. After stating Lynch was being held by hostile forces, the military waited 24 hours to rescue her so they could make a propaganda film.

Peter Phillips, the director of Project Censored at Sonoma State University, says the Pentagon has spent $1 billion on public-relations firms to create stories that protect or enhance the image of the military. These firms “will lie for their clients; that’s what they do,” Phillips says. “The news coming out of Iraq is very much packaged by PR firms and embedded reporters.”

Families Deceived

But all-American hero Pat Tillman was one of at least three soldiers killed in Iraq or Afghanistan during a two-month period whose families were lied to about their deaths.

Mountain View resident Karen Meredith lost her only child, Lt. Ken Ballard, on May 30, 2004, just days after the military says that Tillman had died from friendly fire. Speaking at Ballard’s memorial service, an officer recounted that Ballard’s heroics saved the lives of 60 men. Ballard was awarded the Bronze Star.

“The officer says how Ken fought and fought and fought to cover for two platoons so they could get back to base,” Meredith remembers. “Given his heroism, I questioned why Ken was not given the Silver Star [a higher honor than the Bronze Star]. He said that the Silver Star was very rare. I didn’t trust them, but I was still grieving and thought I’d have time to think about that later. I vowed that Ken would get every award he deserved, so I started asking for the incident report.”

Fifteen months after Meredith’s son died, Lt. Col. John O’Brien, the head of the Army casualty division, visited her at her home. Rather than recounting a heroic story of a death that saved 60 lives, O’Brien told her that her son had been killed by an accidental discharge of the unmanned M-240 machine gun on his tank.

“My life was in upheaval–I believed what I believed for 15 months,” Meredith says. “My heart was ripped open again.”

Nadia McCaffrey, whose son Patrick McCaffrey worked as a manager at a Palo Alto automotive shop, says she was told that her son, a member of the National Guard, was shot and killed by insurgents in an ambush. In the spring of 2004 as the Abu Ghraib prisoner-abuse scandal inflamed the Middle East, McCaffrey, assigned to train Iraqi soldiers allied with American troops, became worried about his safety. His mother says that he feared the Iraqi troops would turn on him.

“He had said in an e-mail that because of Abu Ghraib every [U.S.] soldier had a bounty on his head,” McCaffrey remembers, adding that Patrick was “ashamed” by the reports of torture in Iraqi prisons and that U.S. troops were viewed as occupiers.

The divorced father of two young children, McCaffrey, 34, died near Balad, Iraq, on June 22, 2004. It was two years later, Nadia says, that she learned her son was murdered by two Iraqi civil defense force soldiers he was training.

Jesse Buryj’s family was told he was killed in a vehicle accident. Buryj, of Canton, Ohio, died May 5, 2004. A year later, his parents and young wife received the autopsy report, and they found instead that he was shot in the back by allied soldiers. The Military Times still lists the cause of his death as a vehicle accident.

Yet it was Pat Tillman’s tale that riveted the nation. Tillman was the essence of the young, idealistic and intelligent American. Strong in mind and body, a maverick who was willing to make the ultimate sacrifice, placing concern for his fellow Rangers above his own safety, Tillman was a loyal son, good brother and loving husband. And he was a football star with rugged good looks. It’s no accident that he became, against his wishes, the poster boy for the Bush administration’s endless wars.

Shared Sacrifice

Mary Tillman, a teacher at a San Jose middle school, says that her son joined the Army because he believed that “the country was in danger, the country was in need and football seemed trivial.” In a telephone interview, she says that her son believed in shared sacrifice and that the military should be made up of people all across society, not just those who needed a job.

“It was also an experience,” she adds, saying that Tillman was always seeking the exhilaration and understanding that came from placing himself in novel, uncomfortable or challenging situations. He always sought to live passionately.

For Tillman, the football field was a place where he could express his exuberance. Paul Yllana, now an assistant high school principal, played football with Tillman at Leland in the early 1990s. Yllana says Tillman was the best player on the team and the key to its 1993 Central Coast championship.

“He was selfless even at 14 years old. He credited his teammates, coaches–he never took credit. He was our captain, our leader, the guy we followed,” Yllana says. “His emotion and drive fueled the rest of the team. I already saw his sense of commitment in high school. He worked harder and longer than anyone else, and he enjoyed it.”

Tillman had an “intense, emotional approach to the game,” Yllana remembers. Not only was he the defensive star, he was one of the team’s running backs. “He wasn’t physically enormous, but he could see and react so much faster than everybody else. He had incredible vision for a high school athlete.”

Despite Tillman’s accomplishments in high school football, Yllana says that most colleges weren’t interested in an “undersized” player (Tillman was 5-foot-11). “ASU took a chance and gave him their last scholarship, and he became Pac-10 defensive player of the year.”

But Tillman never let his commitment to football interfere with his pursuit of knowledge. He graduated from ASU in less than four years with a 3.84 grade point average. The Arizona Cardinals selected him with a seventh round pick, making him the 227th player drafted.

“They gave him a shot because he’d played for ASU and was a ‘hometown kid,'” Yllana says. But it was a long shot; few seventh-rounders establish themselves in the NFL. After defying the odds and becoming one of the league’s better safeties, Tillman was offered a five-year, $9 million contract from the St. Louis Rams. He turned it down to stay with the Cardinals, the team that gave him a chance.

“We told him the Cardinals would have matched the offer, and he said, ‘Really? Damn!'” says Joe Nedney, a kicker with the San Francisco 49ers who played with Tillman for Arizona in the late ’90s.

Nedney recalls Tillman had “long, flowing hair and wore flip-flops and T-shirts and tattered shorts.” Rather than go out and buy a $50,000 truck with his signing money, Nedney says, Tillman rode a Schwinn beach cruiser bicycle to the practice field.

“He was the epitome of the California boy. But inside, he was an extremely well-read and educated man,” Nedney says. “You could get into any conversation with him, and he would hold his own. We used to joke that you have to do your homework before you spend time with Pat.”

Jared Schreiber, who befriended Tillman at ASU and serves on the board of the Pat Tillman Foundation, remembers, “It was impossible to sit down with Pat without getting into a great debate. Politics and religion, world events–he was so well-informed on issues, so capable of making other people interested. It was never about him or his own opinion. It was about understanding what’s important and pursuing it with passion.”

Tillman also “thirsted for the adrenaline rush,” Nedney says. He remembers that on one day off from football practice, some players and their wives were socializing when someone asked, “Where’s Pat?” Nedney says, “Right after that we saw two flip-flops and a T-shirt hit the ground–Pat was up there on the roof.” A teammate tried to talk him down but Pat vaulted into a long arcing leap, did a back flip and plunged into the pool.

“His wife, Marie, shrugged as if to say, ‘What do you want me to do?’ He came up and gave a big ol’ ‘Whoo!’ and grabbed his beer. He was an adventure freak, always looking for something to defy gravity, logic and sanity.”

After the 9-11 attacks, Tillman began thinking about joining the military. He fulfilled his contract and completed the 2001 NFL season. In May 2002, Pat and his brother Kevin, a professional baseball player in the minor leagues, enlisted in the U.S. Army. The brothers completed Ranger indoctrination later that year and served in Iraq in 2003 before being redeployed to Afghanistan.

Nedney wasn’t surprised when Tillman joined the military. “He was always searching for something meaningful. He talked to his wife, made a decision and never looked back. Coach [Dave] McGinnis [Arizona’s coach at the time] says, ‘You’re going to run into a media shitstorm,’ and Pat says, ‘No, you are–I’m outta here.’

“I thought he’d come back with bin Laden’s head in one hand and Saddam’s in the other.”

Though she’s hesitant to speak for her son, Mary Tillman says that Pat opposed the war in Iraq. He joined the military to root out al Qaida, not to wage war on a country that had no connection to the 9-11 attacks. Regarding Iraq, she says, “Pat and Kevin felt there was no plan, no threat. It was really disturbing.”

April 22, 2004

On April 22, 2004, Tillman and his platoon were in southern Afghanistan, near the border with Pakistan, looking for Taliban insurgents. According to the Department of Defense Inspector General’s report, after a Humvee had a mechanical problem, the soldiers split into two groups, Serial One and Serial Two. Pat Tillman was in the first group, which moved ahead of Serial Two. Kevin Tillman remained at the rear of Serial Two.

After Serial Two was fired upon by suspected insurgents, Serial One moved up the canyon to target the shooters. An Afghani soldier with Serial One began shooting over the canyon. Believing the Afghani was an insurgent, Serial Two soldiers began firing and killed him. Other Serial Two soldiers began shooting in the same direction, driving closer and continuing to fire even after soldiers signaled they were “friendlies.”

That’s when Tillman detonated a smoke grenade, hoping his fellow soldiers would recognize him and his men. When the shooting stopped, Tillman probably believed they were identified and stood up, but a moment later another burst of fire shattered the Afghani evening.

“I noticed blood pooling up around me. I had thought that I was shot,” Ranger Bryan O’Neal told the Oversight panel. O’Neal served alongside Tillman and believes that he may be alive today thanks to Tillman’s efforts. “I was on the ground, and so I started communicating with Pat, not realizing he had passed away, asking him if he was OK. And I had no response. There was a lot of blood everywhere, and I was starting to get really worried. When I could finally get my body to move, I stood up and turned around and looked at Pat, and he was slumped back on the ground, covered in blood. I went up to his position. I grabbed him and realized . . . that he had been shot in the head, and there wasn’t much left of him.”

At the age of 27, Patrick Daniel Tillman Jr., who had seemed as invincible on the battlefield as he’d been on the football field, was killed by American bullets. But that’s not what military commanders told the Tillman family.

‘Outright Lies’

Within hours of Tillman’s shooting, Army officers ordered the burning of his blood-soaked uniform and the destruction of his bullet-riddled body armor. Army spokesman Paul Boyce says soldiers had already determined that friendly fire caused Tillman’s death and burned his clothes and armor because they viewed these items as a biohazard.

Destruction of evidence in a case of friendly fire is a violation of U.S. military regulations. Soldiers also burned his journal, the Army Inspector General’s report stated. “I’m angry they did that,” says Mary Tillman. The soldier who destroyed Tillman’s clothing, body armor and possessions says he was ordered to do so “to prevent security violations, leaks and rumors.”

When the soldier commented that the bullets that shredded Tillman’s body armor appeared to be American, he was told to “keep quiet and let the investigators do their jobs.” According to the IG’s report, commanders cut off telephone and Internet communications at a base in Afghanistan and posted guards on a wounded soldier, Bryan O’Neal, from Tillman’s Ranger unit. The Tillmans believe this was done to keep O’Neal from speaking with reporters and revealing what happened.

Though it’s Army protocol to notify the family as soon as friendly fire (also known as “fratricide”) is suspected, O’Neal testified that he was ordered by battalion commander Lt. Col. Jeffrey Bailey not to tell Kevin Tillman that fratricide appeared to be the cause of his brother’s death.

“Although some within the chain of command were aware of the suspicion that Cpl. Tillman died as a result of friendly fire, they did not publicly reveal this information, because they wanted to ensure a thorough investigative process,” says Army spokesman Boyce. Several changes have since been implemented to ensure more timely notification in suspected friendly-fire cases, Boyce says.

Citing the IG report, Rep. Waxman says that within 72 hours “at least nine military officials knew or were informed that Pat Tillman’s death was a fratricide, including at least three generals.” The report charges that the “chain of command made critical errors in reporting Cpl. Tillman’s death.” But the Inspector General did not find a single instance of criminal negligence.

Waxman asked O’Neal, whose statement about the fratricide was changed in the documentation for Tillman’s Silver Star award, if it “troubles” him that “the Tillman family was kept in the dark” about Pat’s death for more than a month.

“Yes, sir, it does,” O’Neal said. “I wanted right off the bat to let the family know what had happened, especially Kevin, because I worked with him in the platoon. I knew that he and the family all needed to know what had happened. And I was quite appalled that when I was able to speak with Kevin, I was ordered not to tell him what happened, sir.”

“You were ordered not to tell him?” Waxman asked.

“Roger that, sir,” O’Neal replied, stating the order came from Bailey. “He basically just said, ‘Do not let Kevin know. He’s probably in a bad place knowing his brother’s dead.’ And he made it known,” O’Neal continued, “that I would get in trouble, sir, if I spoke with Kevin on it being fratricide.”

Ranger Spc. Russell Baer, who had seen Rangers shooting at Pat Tillman’s position, accompanied his friend Kevin Tillman from Afghanistan to the United States after Pat was killed. According to Associated Press reports, Baer says that he was ordered not to tell Kevin Tillman that friendly fire was the probable cause of Pat’s death. Baer followed orders and did not tell Kevin he’d seen Rangers firing toward Pat. Baer later went AWOL. Testifying in one of the probes into Tillman’s death, he explained, “I lost respect for the people in charge.”

Speaking at Tillman’s nationally televised memorial service on May 3, 2004, Navy SEAL Stephen White, who befriended Tillman in Iraq, spoke of Tillman’s bravery and heroism as he “took the fight to the enemy, uphill to seize the tactical high ground,” repeating what Army commanders had told him: “Pat sacrificed himself so others could live.”

When White found out weeks later that the story he’d told the nation had been a lie, he felt “let down by my military,” he said at the Oversight hearing. “I’m the guy who told America how he died, and it was incorrect. That does not sit well with me.”

Tillman’s father, Patrick Tillman, believes senior Army officers told “outright lies” about his son’s death. In 2005, he told the Washington Post: “All the people in positions of authority went out of their way to script this. They purposely interfered with the investigation, they covered it up. I think they thought they could control it, and they realized that their recruiting efforts were going to go to hell in a hand basket if the truth about his death got out.

“They blew up their poster boy.”

False & Spun

More than three years after Pat Tillman died, his family still has questions. They want to know why battlefield rules of engagement–rules that could have prevented Pat’s death–were not followed; why military and government leaders lied to them; who gave the orders to create the fictional account of Pat’s heroism; and why no one has been held accountable.

“Pat’s death is just a microcosm of what’s happening in this country–the lies, the spinning,” Mary Tillman says. “This exemplifies the way the [Bush] administration handles everything. They’re incompetent, yet no one is held accountable. The documents were falsified–but who are these people? What are you going to do about it?”

Citing connections to the failed federal response to Hurricane Katrina and the debacle at the military’s Walter Reed hospital, Mary Tillman charges, “There’s a lack of empathy on the part of the administration. It’s all lip service. There is no genuine appreciation for the suffering that’s taken place.”

Rep. Waxman is continuing the probe into Tillman’s case and has sent letters to Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and to the White House counsel requesting communications about Tillman’s death.

Mary Tillman, a registered Republican, says, “The personalities in office now are dangerous.” She believes former secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld, whom she calls a “micromanager,” had to know before Pat’s memorial that her son was killed by friendly fire. Rumsfeld had written a letter to her son, she says, and was well aware of Tillman’s celebrity.

“[Pat] was probably the most high-profile individual in the military at the time,” she says. “The fact that he would be killed by friendly fire and no one would tell Rumsfeld is ludicrous.”

Mary Tillman believes that President Bush knew as well.

On April 28, 2004, six days after Pat died, White House speech writer John Currin sent the Pentagon an e-mail asking for information about Tillman’s death for a speech Bush would deliver at the upcoming correspondent’s dinner. The next day, according to testimony at the Oversight hearing, a high-priority P4 memo was sent to three top generals, including Gen. John Abizaid, then head of Central Command, stating it was “highly possible that Cpl. Tillman was killed by friendly fire.”

Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Maryland, said this memo “seems to be responding to inquiries from the White House, and here’s what it says: “‘POTUS–meaning President of the United States–and the Secretary of the Army might include comments about Cpl. Tillman’s heroism [without mentioning] the specifics surrounding his death.'” The memo, whose author wasn’t disclosed, expresses concern that the president and Rumsfeld could suffer “public embarrassment if the circumstances of Cpl. Tillman’s death become public.”

When the president spoke at the correspondents’ dinner the following Saturday, “he was careful in his wording,” Rep. Cummings said at the Oversight hearing. “He praised Pat Tillman’s courage, but carefully avoided describing how he was killed. It seems possible that the P4 memo was a direct response to the White House’s inquiry. And if that is true, it means that the White House knew the true facts about Cpl. Tillman’s death before the memorial service and weeks before the Tillman family was told.”

Though Mary Tillman has been frustrated by the Bush administration’s resistance to her inquiries, the family has had some contact from the president. During a halftime ceremony in September 2004 to retire Pat Tillman’s jersey at an Arizona Cardinals game, a video of the president was shown.

“[The Cardinals’ management] didn’t ask us if it was OK to broadcast the video,” Mary Tillman says, adding that thousands in the Arizona crowd booed Bush. “I was angry. It was just [the Bush Administration’s] way of using Pat one more time–it changed the tone of everything.”

Family from Hell

Perhaps the most revealing statements about the heartlessness of Tillman’s military superiors came from Lt. Col. Ralph Kauzlarich, who directed the first official inquiry into Tillman’s death. Kauzlarich says the Army did ballistics work and may know who shot Pat Tillman. “I think they know [who fired the shots that killed Tillman],” Kauzlarich said in an interview with ESPN. “But I never found out.”

Speaking of the Tillman family, Kauzlarich said, “These people have a hard time letting it go. It may be because of their religious beliefs.” Noting that Kevin Tillman declined to have a chaplain say prayers over Pat’s body, Kauzlarich continued: “When you die, there is supposedly a better life, right? Well, if you are an atheist and you don’t believe in anything, if you die, what is there to go to? Nothing. You are worm dirt.”

Mary Tillman says she’d like nothing better than to let go. “I’d like for this to come to a conclusion so we can focus on the more positive aspects of Pat’s life,” she says. But she’s not going to move on until she gets the truth.

Norman Solomon applauds the Tillmans’ courage and perseverance in trying to uncover what happened to Pat.

“They’re tough, smart and not intimidated,” he says. From the Pentagon’s perspective, “the Tillmans have become the family from hell.” But overcoming a widely distributed and oft-repeated lie isn’t easy, Solomon says, because “first impressions are imprinted on people.”

As Mark Twain said more than a century ago, “A lie can get halfway around the world before the truth even gets its boots on.”

Pat’s Run

As the sun broke through a layer of misty clouds in San Jose on the last Sunday morning in April, thousands of runners gathered outside Leland High School for Pat’s Run. The run is a fundraiser for the Pat Tillman Foundation that has raised $4 million so far to support high school and college students engaging in projects for social change. The event draws soldiers, football players, war opponents and cheerleaders. There’s not a trace of political activism, just 5,000 amateur athletes united in their desire to honor Tillman’s memory and support the foundation.

At Leland’s field, renamed “Pat Tillman Stadium,” 15-foot-high burgundy balloon clusters spell out “Pat’s Run.” A quote from Emerson is posted at the finish line: “Do not go where the path may lead; go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.” Some runners race to the finish; others push strollers or jog with their dogs over the 4.2-mile course (42 was Tillman’s football jersey number in high school and college).

After running the race, USMC Lt. Steve Cooney of Santa Rosa called Tillman “a strong American who died an honorable death fighting for his country.” Another soldier, Army reservist Michael B. of Santa Clara, who declined to give his last name, says he understood how friendly-fire deaths can happen, “but if it were my family, I’d want them to know the truth.”

Melanie Corpus, a young woman from San Jose, had the Pat’s Run logo inked on her cheek. She became tearful when speaking about Tillman, saying that he had touched people who didn’t know him personally. “He gave up everything,” she says. “He was just a beautiful person.”

Many who attended the run didn’t know the Tillman family had been deceived about Pat’s death. But some had read about the official mendacity. Jennifer Green of San Jose says she “liked Tillman even better” once she learned the truth about him. “He was a thinker; he read [Noam] Chomsky, he joined [the Army] for all the right reasons.”

Arizona State University student Mackenzie Hopman is enrolled as a Pat Tillman Scholar in ASU’s one-year, accredited Leadership Through Action program, created after Tillman’s death to encourage students to engage in community projects. She traveled from Tempe to be part of the run.

Hopman became a Tillman Scholar because she was inspired by him. “As Pat was walking down the long corridor of life, he had goals in mind: ASU, pro football, the military,” Hopman says. “There were doors on either side of this corridor, and instead of breezing past each door, he’d stop and peek inside and then run a few yards and leave it behind. He never lost sight of what was ahead of him and where he wanted to be. He was always there 150 percent, every day, every practice, every moment.”

Alex Garwood, Pat’s brother-in-law and executive director of the Tillman Foundation, ascends a podium to hand out trophies as U2’s “It’s a Beautiful Day” sweeps across the field.

“What a positive day,” Garwood says in an interview after the ceremony. “But we should not have to be doing this. Pat should be here.”