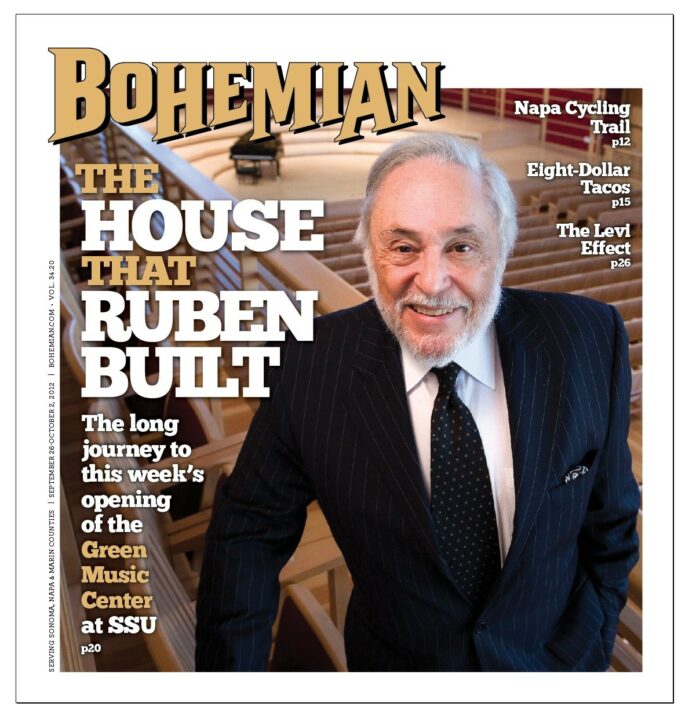

Five days before the grand opening of the building that is to be the pinnacle of his career, Sonoma State University president Ruben Armiñana leans back in his office chair, breathes a reflective sigh and tells a story made for Hollywood.

“I made a promise to a 14-year-old boy,” Armiñana says, “on Nov. 6, 1961. His name was Ruben. And he was leaving his country that day, he was leaving his parents. At that moment, he didn’t know if he would ever see his parents or his brother again. He had a lot of wealth with him—he had a dime and he had a change of underwear. But he had this ability to be determined that nobody, be it government or individuals, would ever intimidate him. And he would never retreat in the face of intimidation. And I have kept that promise for 50 years.”

It’s difficult to overstate the magnitude and impact of the Green Music Center, opening this weekend at Sonoma State University. No project has more greatly tested Armiñana’s promise to himself, over 50 years ago, as he was shipped on a boat from Cuba to the United States. The $145 million performing arts and music education center has taken almost 20 years to arrive at its current state, and is still not entirely finished.

The main hall, however, which opens this weekend, has already garnered worldwide attention for its stunning acoustics and dazzling first-season lineup of stars like Yo-Yo Ma, Lang Lang, Michael Tilson Thomas, Alison Krauss and Wynton Marsalis. There are few concert halls comparable, let alone ones on a college campus.

But to say it was a bumpy road to this weekend’s opening is like saying this one guy named Mozart wrote a few good tunes. Just like the works of the famous 18th-century composer, it will only be with the passing of time that the legacy of the Green Music Center—and the legacy of Ruben Armiñana—is truly realized.

Is this the president’s Spruce Goose? His Hearst Castle? On the cusp of opening night, it’s looking a lot more like Carnegie Hall.

Opus One

At age nine, living in Santa Clara, Cuba, the young Armiñana found himself enrolled in a violin class; his mother believed all educated people should learn to play an instrument. “Halfway through the class,” he tells, “the teacher called my father and said, ‘Why don’t you come and pick up your son? I know he has talent. This is not it. Why destroy your pocketbook, and my ears?’ And that was the end of my musical career.”

Somewhere, the camera is cutting to an image of that violin, engulfed in flames, with the word “Rosebud” on it. If Armiñana is making up for being kicked out of the class by building a grand hall for classical music, then, based on the scope of the Green Music Center, he must have really felt bad.

The main hall alone has rightly been declared an acoustic marvel. Featuring six different kinds of wood, the room can be “tuned” for resonance using panels in the ceiling and on the walls. The stage can be pulled out in different tiers for the orchestra or pushed back to maximize performing floor space. Even the chairs, with a total price tag of $1.2 million, have unique, individual bevels corresponding with the slope of the floor, designed for maximum acoustic transparency.

Pushing the space into the upper echelon of concert halls is the HVAC system, oversized for its needs, silently keeping the room at a constant temperature for both the comfort of the audience and the tuning of instruments. The back of the hall opens to a terraced lawn, allowing for over 3,000 additional seats. And though they’re technically unnecessary, because the design of the hall shoots sound out the opening at a perfectly audible volume, speakers amplify the audio outside, and 18 downfiring subwoofers shoot sound into the ground for a natural low-end feel.

[page]

This main hall is only one piece of the Green Music Center, which currently includes a music education wing and top-tier restaurant. When finally completed, it will also boast a 10,000-seat outdoor concert venue and an intimate, 250-seat student recital hall with a full pipe organ.

When conceived, the Green Music Center was, in Armiñana’s own words, “a crazy idea.” Even from the start, detractors pointed out its high cost and questioned how it would benefit the university—criticism that continues to this day.

But against all odds, the 65-year-old’s dogged persistence, carried to America along with the dime and a change of underwear, prevailed. “The toughest time,” he says, “is when it’s just an idea.”

Intonation

“I know that we started fundraising before the tech bubble crashed,” remembers Chris Fritzche, a former voice instructor at Sonoma State who later toured with the male vocal ensemble Chanticleer. With only small spaces for music at the time, large performances were relegated to places like the gymnasium, which sounded like—well, a gymnasium. “I don’t know what was in their minds,” Fritzche recalls, “but the impression I got was for SSU to have a choral hall for the choral program to have a place to perform with a good acoustics.”

Indeed, this was the vision of Don and Maureen Green, who were members of Bob Worth’s Bach Choir in the mid 1990s. Recalled Armiñana in a recent email, Don Green “mentioned that he was planning to take his company, Advance Fibre Communications, public, and if that was successful [he] hoped to make a contribution, about $1 million, to build a choral room for the choir to rehearse and perform on campus. We did not have such a facility.”

At the same time, Armiñana visited Massachusetts with his wife for a concert at Tanglewood’s Seiji Ozawa Hall, which had been finished in 1994. “I came back from that visit with the idea of creating an inspired facility like Ozawa Hall at SSU which would combine education, music and performance,” he says. After their company went public, the Greens had dinner with Armiñana and decided to give $5 million toward the project. The next summer, the Greens themselves visited Tanglewood, and committed another $5 million.

That landmark $10 million donation all but assured the $22 million acoustic masterpiece would be open by the early 2000s. But costs began to rise like the sound of a Prius accelerating onto the freeway. Estimates hit $29 million in 2003. Then $39 million in 2004. It was $60 million in 2005, and by 2007 it had cracked triple digits with a $100 million price tag.

But Armiñana never gave up his dream, even after a vote of “no confidence” by the university’s faculty in 2007, tied in part to concerns that the GMC was sucking sorely needed funds away from other areas of academia.

“I thought [the vote] was unfair,” responds Armiñana, somberly. “But it clearly pointed out that we needed to be better communicators about the role of the university,” adding that “it was part of the politics at that time of very strained relations with the faculty union.”

Accelerando

Armiñana says his lowest point, personally, came in 2008 when construction bids began to skyrocket. The price of steel was rising by 5 to 10 percent each month. Estimates were coming in higher than expected. Then, the economy suddenly took a nosedive. The university seemed to be chasing a rainbow.

But still, “Cabeza Dura,” or “Hard Head,” as his mother called him, persisted. After $47 million in state bonds helped complete the music education hall, it was decided the rest of the Green Music Center would be funded privately. In nearly every public appearance over the next four years, Armiñana pled his case and asked for money. Thousands of individuals came forward with small amounts, but it was the large donors that propelled the project forward when fundraising efforts stalled.

Notable donations included $5 million from Jean Schulz, wife of cartoonist Charles Schulz; just over $3 million from telecom pioneers John and Jennifer Webley; $3 million from former Press Democrat publisher Evert Person and wife, Norma; $1.4 million from the GK Hardt Foundation; $1.2 million from former OCLI CEO Herb Dwight and wife, Jane; $1 million from the Henry Trione Foundation and $1 million from winery owners Jacques and Barbara Schlumberger.

The most notable donation, after the initial $10 million given by the Greens, came from former Citigroup chairman and CEO Sandy Weill and wife, Joan. Weill heard about the project from a neighbor after the couple moved from New York into a $31 million estate on Sonoma Mountain. “I knew we had horses, lambs, sheep, and a lot of land,” he said at a press conference in March, “but nothing about a music center.” Weill’s musical background was limited to playing bass drum in a military band, but his curiosity was piqued. “It really looked like a gem,” he said. “I spoke to Lang Lang, and said, ‘You gotta do me a favor.'”

[page]

Soon, Lang Lang, the globally acclaimed concert pianist who opens the Green Music Center this Saturday, visited Sonoma State at midnight to be silently ushered into the main hall for a trial run. At 1:30am, after an hour and a half at the piano, the pianist gave the hall his blessing. Subsequently, Weill gave the hall $12 million.

The thing that was once just an idea was becoming more and more tangible. As Armiñana is fond of saying, the tires on the car were finally able to be kicked. “If we had not built it to the point we had,” says Armiñana, “I don’t think the Weills would have come in, visited one time and then called back saying, ‘How much do you need?'”

The reverberations of Weill’s involvement were wide. Weill’s financial connections led to a $15 million donation from Mastercard to name the as-yet-unfinished 10,000-seat outdoor performance space. But it also led to some activists vowing to speak the newly christened words “Weill Hall” in the original German pronunciation.

Dissonance

Weill, who did not respond to a request for an interview for this story, is a board member for Carnegie Hall and a noted philanthropist with a history of donating to the arts and to universities. Yet many assert his responsibility in the financial meltdown of 2008, beginning with his flouting of regulatory laws in merging Citicorp and Travelers Group in 1998. Weill then lobbied successfully to repeal the Glass-Steagall act, which opened the doors for other banks to follow his lead and grow too-big-to-fail. He was named one of the “25 People to Blame for the Financial Crisis” by Time magazine, and there was even a minor protest at 2012’s commencement ceremony at SSU, at which Weill and his wife, Joan, were presented with honorary degrees from the university.

Armiñana understands why people felt the need to demonstrate. “There is not a great deal of love at this moment, nationally, toward big banking,” he says. But he feels that Weill is not to blame. Citing the House’s passage and President Clinton’s signing of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, Armiñana says laying blame solely on Weill for the repeal of Glass-Steagall “shows a great deal of lack of knowledge of how the legislative executive process works in the United States.”

For his part, Weill has since reexamined his position, stating this July that government regulations are necessary to prevent economic collapse. (“I have found him very nimble in his mind,” notes Armiñana.)

Weill’s history aside, some faculty believe the GMC has diverted funds and attention away from other areas of the university. In a study released this year by SSU sociology professor Peter Phillips, 14 of 16 department heads interviewed under condition of anonymity said they felt “GMC development efforts directed funds away from the quality of education throughout Sonoma State.” Overall, those interviewed felt that the GMC “might not have been the best venture,” the study says.

“The university has no business being in the concert business; we’re in the education business,” says Phillips. “All these resources are being put into this music hall, which is essentially for the Sonoma County upper crust.”

Armiñana has not read the report, but allows that he is familiar with it. “I have had encounters in the past that Peter’s methodologies have been very biased,” he says, choosing not to comment further.

[page]

Additionally, students and faculty in Sonoma State’s music department are eager to see the completion of the 250-seat Schroeder Hall. A medium-sized, acoustically pleasing cousin of the 1,400-seat main hall, Schroeder Hall is the closest thing to the Green’s original vision, yet remains unfinished, needing $5 million for completion. In the meantime, most student ensembles meet and perform in GMC 1028 or 1029, which are boxy rooms with odd acoustics. “I believe when Schroeder Hall opens, it will be mostly academic focused,” says administrative coordinator Caroline Ammann. “We can get students in there, it’s the perfect place.”

University CFO and executive director of the GMC Larry Furukawa-Schlereth understands the criticism, but doesn’t feel it will stick in the long run. “It’s difficult when a project is in the planning stage or building stage for people to fully understand its impact,” he says. “Once a thing is completed, people become more aware of the importance of a project.” He adds that the controversy surrounding the Green Music Center has not been any greater than any he’s experienced on campus, including the Schulz Information Center, which was completed in June 2000, one month after the CSU Board of Trustees approved a master plan adding the 48 acres for the GMC.

“Now,” says Furukawa-Schlereth, “people can’t imagine the university without the operations of the Schulz Information Center. I think the same is true with the music center.”

Coda

Though he exudes a sense of modesty about it, Armiñana is, by all accounts, the person who took the idea for a small choral hall and turned it into a world-class performing arts facility. He persevered in the face of adversity, both financial and personal. “By nature,” he says today, “I’m not a quitter.”

Even when a large donor suggested otherwise, Armiñana would not stray from his vision. “I had a conversation with somebody who is no longer on earth,” he says, declining to name names, “who said, ‘Here, you have my money, why don’t you just build a tent to do summer things, et cetera. You can build a really nice tent with the money you’ve got.'” But straying from the original plan was not an option. “We were never willing to compromise,” says Armiñana. “There were chances, and requests, to compromise the quality, and the answer was absolutely no. Once we made the decision of what the full scope of the project was, there was never a doubt to do it all.”

Does the controversy bother him? “Not at all,” he responds, matter-of-factly. The Green Music Center and other capital improvements made under Armiñana’s tenure (the Schulz Information Center, the Salazar and Darwin Hall renovations and student recreation facilities, among others) will remain integral parts of the educational experience far after he retires, and “if people think I did this to create a legacy, I just don’t operate that way,” he says.

“I think soon, someday,” he says, “they will forget Ruben Armiñana.”

—

Grand Opening Weekend

Sept. 29 Lang Lang, piano, in program of Mozart and Chopin. 7pm. Indoor seating sold-out; $20–$55 lawn tickets available.

Sept. 30 Sunrise Choral Concert, community and university choral ensembles. 7am. Free; advance tickets required.

Sept. 30 Santa Rosa Symphony, with Corrick Brown, Jeffrey Kahane and Bruno Ferrandis. 2pm. Indoor seating sold-out; $10 table and free lawn tickets available.

Sept. 30 Alison Krauss & Union Station. 7:30pm. Indoor and lawn seating sold-out.

Upcoming performances include Bill Maher (Oct. 20), John Adams (Oct. 27), Aziz Ansari (Nov. 4), Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony (Dec. 6, Mar. 7), Yo-Yo Ma (Jan. 26), Anne-Sophie Mutter (Mar. 2), Wynton Marsalis (Mar. 21) and others. See www.gmc.sonoma.edu for full schedule and ticket information.